Dear investors,

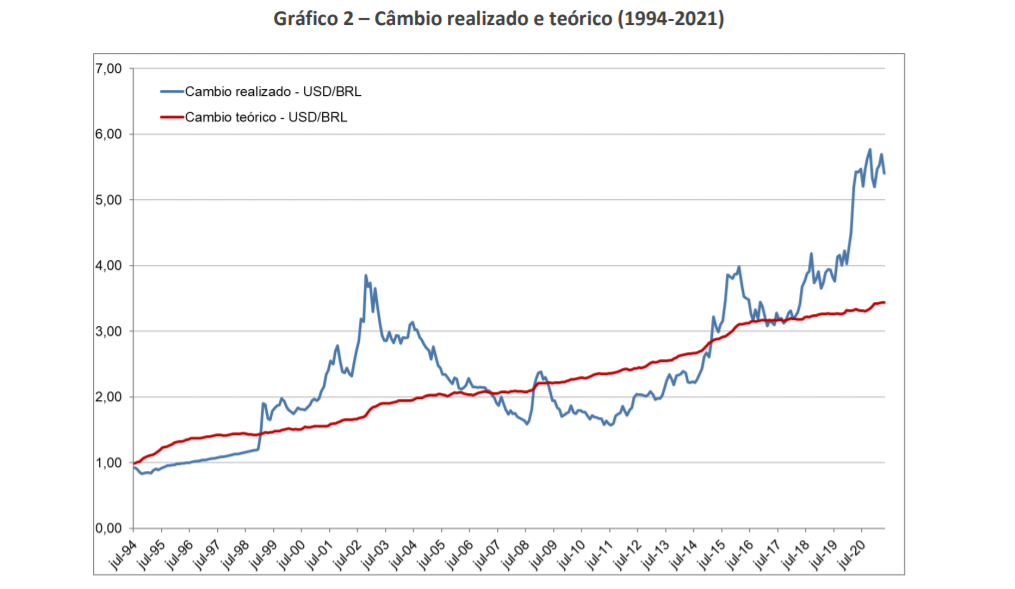

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis in 2020, the dollar exchange rate has fluctuated between R$ 5.00 and R$ 6.00, close to the historical peak value recorded on May 14, 2020, when the dollar exchange rate reached R$ 5 .93, the highest nominal value since the inception of the real in 1994.Although we are already getting used to the dollar at this level, it is worth remembering that, in the 5 years prior to the crisis, the American currency fluctuated between R$ 3.00 and R$ 4.00 and, at the beginning of the last decade, the dollar was quoted close to to R$ 2.00.

Faced with such distant values, the question arises: what is the fair value of the dollar? And where does he go?

In this letter, trying to help answer these questions, we update a study that we first did in 2013, which collects data over 50 years and estimates what the breakeven value for the exchange rate would be.

Although there are a number of theories that try to explain what the “equilibrium” exchange rate is, it is impossible to predict it exactly. On a daily basis, this rate is determined by the laws of supply and demand in conversion operations between different currencies. For example, if there is a very large flow of foreign investors interested in investing in Brazil, they need to convert their dollars into reais. With this, the demand for reais increases and our currency appreciates, as happened in 2010-2011.

In the most recent Focus bulletin from the Central Bank, the expectation of market analysts is that we will end the year with the dollar around R$ 5.40 – at the beginning of the year, these same analysts predicted the dollar at R$ 5.00 at the end from 2021.

As Edmar Bacha, one of the creators of the Real Plan, put it well, “the exchange rate was made by God to humiliate economists”.

However, in the long term, studies indicate that what determines the exchange rate level is the maintenance of purchasing power parity between currencies. Using the example of the Big Mac Index, created by The Economist magazine, we can illustrate its logic. In 1994, a Big Mac cost R$ 2.42 in Brazil. In 2021, the same sandwich costs R$ 21.90, a 9.0 times price increase over the period. What is the reason for this increase? It stems mainly from the inflation of raw materials and the cost of labor in the country. The minimum wage went from R$ 64.79 in July 1994 to R$ 1,045 today (an increase of more than 16 times) and the price of an arroba of fat cattle has multiplied by 14 in the last 27 years.

In the United States, a Big Mac cost US$ 2.32 in 1994. American inflation in this period was more contained than ours, and today a Big Mac is sold for US$ 5.66. The trade-off ratio implied in the price of the Big Mac in the two countries was 1.04 in 1994 (R$ 2.42 / US$ 2.32), and is 3.9 today (R$ 21.90 / US$ 5.66) . Its evolution in this period reflects price variation unevenly in both countries. Not by chance, in 1994 the exchange rate was such that one dollar was worth one real, and before the crisis caused by Covid-19 the ratio was oscillating around R$ 4.00. Indeed, studies have already shown that the Bic Mac Index is surprisingly accurate at tracking trends in exchange rates across countries over the long term¹.

We analyzed the relationship between the exchange rate and inflation for a series of currencies from different countries, covering a period of more than 50 years, and in all cases, the purchasing power parity relationship appears to be quite solid. The case of Brazil is the most emblematic because, since 1960, we have had 8 different denominations of currency (Cruzeiro, Cruzado, Cruzeiro Novo etc.), periods of hyperinflation and we cut 9 zeros from the currency. The nominal exchange rate varied significantly: 1 dollar bought 12,985 cruzeiros in February 1986, and only 0.84 reais in October 1995.

When we analyze the historical exchange rate of the Brazilian currency against the dollar, removing the effect of the inflation that occurred in both countries, we see that the exchange rate variation is much smaller, and that it oscillates around a balance point.

Graph 1 below, which covers the period since the early 1970s, shows how periods of overvalued and undervalued currencies alternated over time.

Although this methodology does not allow us to make short-term predictions, we are able to make some directional inferences that can be useful in long-term investment decisions.

The first is that, despite having gone through several crises and moments of euphoria throughout our recent history, the exchange rate always reverts to its equilibrium level. Currently this threshold would be between R$ 3.30 and R$ 3.70 – surprising considering current levels.

We only had one other period, 2002, in which the exchange rate fell in relative terms even more than it does now. That is, the value that the dollar reached in May, despite a nominal record, is still not a record devaluation in real terms of our currency against the dollar, which occurred on October 22, 2002. closed quoted at R$ 3.95 which, at today's values, would be equivalent to R$ 7.922. The graph shows how, in some moments of financial stress, the exchange rate took off more sharply from the “fair” value.

Another important point is that periods of currency overvaluation or devaluation can be long. For example, for 8 years, between 1999 and 2006, our currency was significantly devalued and, in the opposite direction, in the next 8 years, between 2007 and 2014, we went through a period where the real remained appreciated against the dollar. Finally, it is important to note that the equilibrium exchange rate increases over time (red line in the graph above). This is due to the fact that Brazil has historically had much higher inflation than that of the United States. As a result, even if the nominal exchange rate remains stationary at its current level between R$ 5.00 and R$ 6.00, the inflation differential between countries may be able to return the exchange rate to a level of equilibrium.

In the current scenario in which inflation is once again a concern for investors, this is certainly a scenario that deserves attention. Our last letter (April/2021) addresses the topic of inflation in more detail and presents our view on why we believe equities act as a hedge against inflation.

¹ Burgernomics: the economics of the Big Mac standard, Journal of International Money and Finance

² Calculated considering the accumulated inflation in Brazil in the period (193%) and discounting the accumulated inflation in the United States (46%) Volume 16, Issue 6, December 1997, Pages 865-878