Dear investors,

In the last month, the IBOV dropped 2%, but the fall was much worse than it appears, as this value is masked by the movement of VALE3, which corresponds to 18% of the index portfolio and rose 28%, against the market. Excluding VALE3, the IBOV would have dropped 9% in November.

The main reason for the drop is the fear of the fiscal policy of the new government, which has made clear its intention to increase state spending on social programs, but has not yet been able to explain where the extra resources for this would come from. Thus, the scenario expected by the market is an increase in the government deficit, with a consequent increase in public debt and interest rates. With high interest rates, economic growth is compromised and stocks lose value. The scenario really looks bleak, but it is necessary to put it into perspective before creating strong opinions about how this reflects on investments.

In our October letter, we commented on Brazil's system of government, and in our November letter, we explored Brazil's position in the global economy. With this background, we will elaborate our view on the most recent facts of the Brazilian market.

The Transition PEC

One of the first acts of the new government was to propose to the National Congress (through agreements with the presidents of the Chamber and of the Senate) a PEC to allow the executive branch to spend ~R$ 198 billion per year, beyond what would be allowed by the ceiling of spending, throughout Lula's term. Of this amount, R$ 175 billion would be related to Bolsa Família under the terms promised in the campaign, and the remaining R$ 23 billion could be spent on investments, but only in case of collections above the forecast in the 2023 budget.

To give these numbers due proportion, the government's fiscal budget for 2023, excluding amounts related to social security and public debt refinancing, is ~R1TP4Q 1.9 trillion. Thus, the proposal named “PEC da Transição” would authorize a real increase of ~9% in these State expenses.

The problem with this PEC is that the new government is asking for permission to spend more without making it clear where the resources to pay for these extra expenses would come from. However, the alternatives are known. There are three main possible sources: i) increased tax collection; ii) issuance of new currency (printing money); or iii) increase in public debt. Let's consider each of these possibilities.

increase in collection

There are only two ways to increase tax collection: raise rates or rely on real economic growth.

In Brazil, the tax burden is around 34% of GDP, a level that is already high (the US, for example, is ~24%). Thus, approving tax increases tends to be a politically very exhausting process, especially for the new Congress, in which most deputies and senators were elected with speeches opposed to this movement. It is not an impossible path, but the tax burden in Brazil has remained relatively stable over the last 10 years, between 32-34%, even at times when the Executive Branch would certainly like to increase its collection.

In turn, economic growth would be the ideal alternative and seems to be the hope of the new government, but it depends on many factors beyond the control of the State, so relying on it has its risk. The situation is similar to that of a company that decides to increase its expenses in the expectation of generating new income: the extra expense is always guaranteed, but the extra income is not.

currency issuance

Ultimately, the state could print new money and use it to pay its expenses. Since issuing currency does not create real economic value, the practical effect of this movement is the appropriation, by the State, of a part of the value of money in circulation in the economy. It is as if the controlling shareholder of a company were to issue new shares for himself, without any consideration, diluting the minority shareholders and reducing the individual value of each share.

The use of this mechanism is always tempting for a government, as the general population understands little about how it works and is more likely to accept inflation resulting from issuing money than an explicit increase in taxes. If the government is free to print money whenever it wants, it tends to abuse this mechanism and cause hyperinflationary crises. Brazil lived with high inflation from the mid-1970s until 1994, when the Plano Real was created and managed to stabilize the country's currency.

The very creation of central banks is related to the need to control currency issuance so that the economy does not enter this negative spiral caused by the practice of issuing currency to finance public spending. The Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) was created in 1965, but has gone through a long process of maturation until it reached, very recently, what are considered good practices.

Until 1988, the BCB's role was confused with that of Banco do Brasil, which greatly reduced the BCB's interference in the country's monetary policy. Until 2020, the BCB was linked to the Ministry of Economy and, consequently, under the Executive Branch, which could replace the president of the BCB at any time and dictate the country's monetary policy. It wasn't until February 2021 that our central bank became independent. Now, the president of the BCB serves a 4-year term, which begins at the beginning of the 3rd year of the President of the Republic and extends until the end of the 2nd year of the next President of the Republic. This recently granted autonomy to the BCB was an important step, as it prevents the Executive Branch from abusing monetary policies.

Today, Brazil has a mature legislative structure to regulate the BCB's activities and its relationship with the National Treasury (TN), which manages the federal government's finances. The main limitations imposed are:

• The BCB cannot grant loans to the National Treasury. The Treasury's debt with the BCB can only be refinanced over time, in an inflation-adjusted amount. This prevents the BCB from issuing currency and passing it on to the TN, which could lead to the vicious cycle of issuing currency to cover fiscal deficits.

• Interest paid by the National Treasury to the BCB is equal to market interest. Transactions between the two institutions cannot be carried out under special conditions.

• The Central Bank's profit from exchange rate variations on its international reserves is maintained at the BCB itself, to cover future losses. This was also a recent evolution, since before, the profit was transferred in cash to the TN and, when there were losses, the TN issued new debt securities to the BCB as payment.

Avoiding technicalities, the general message is that the Brazilian executive branch is not free to simply issue currency to cover its expenses. For that, he would need the support of the president of the BCB and authorization from Congress. It's about as much legislative protection as we could hope for.

Increase in public debt

If the government's collection is not enough and if it is also unable to issue currency to cover its expenses, the only option left for the National Treasury is to issue new bonds to raise money from the market. However, this movement is not completely free either, as the Brazilian constitution limits the increase in public debt through the so-called Golden Rule (Art. 167, item III). According to her, the government can take on new debts to finance investments, but it is not allowed to increase the debt to finance current state expenses (personnel, social benefits, debt interest and funding of the public machine), except when authorized by Congress, by majority. simple.

This limitation may not be completely efficient because, if Congress approves a budget containing additional expenses and the following year's collection is not enough to cover the new expenses, there would not be much to do besides approving that the deficit be covered by new debts. But again, that's about as much legislative protection as we could hope for, as the executive branch and the legislative branch aligned can do just about anything. That is why the market fears this possibility, which would carry two problems:

The first is that resorting to increasing the debt to support current expenses signals fiscal irresponsibility on the part of the government, causing the market to attribute greater risk to loans made to the National Treasury (public bonds) and, therefore, to demand higher interest rates. taller. As a result, government spending on public debt interest increases, worsening the fiscal deficit problem.

The second problem is that by lending money to expand public spending, the government would increase the demand for products and services in the market, which would stimulate an increase in inflation precisely at a time when our Central Bank is trying to reduce it. The consequence tends to be that the Central Bank keeps the interest rate high for a longer time and, thus, hinders the growth of our economy for a longer period.

Impact on stock exchange investments

We have already repeated a few times that the interest rate is the gravitational force of the financial market: the higher it is, the more it pulls asset prices down. This happens because the increase in the basic interest rate also increases the discount rates used in discounted cash flow calculations, the base method for estimating the value of assets in general, and the higher the discount rate, the lower the resulting value. . In addition, higher interest rates reduce the growth expectation of companies and encourage capital to leave the stock market and go to fixed income, intensifying the downward trend. That's why the stock market falls when interest rates rise, and rises again when interest rates fall.

What we've described so far sums up the reason for all the recent market stress. Now, let's take a step back and evaluate this scenario from a broader perspective, involving the aspects that are not part of this logical sequence, but continue to be part of the set of relevant factors for our investments.

tax issue

The trigger for the entire chain of possible fiscal problems that Brazil may have in the future would be the Transition PEC, which has not yet been approved in the proposed format. We know that our Congress is not famous for its agility and pragmatism. The PT's intention is to approve the PEC later this year, but controversial issues tend to take a long time to go through Congress and are quite diluted throughout the process. The Transition PEC may be approved with more lenient terms (permission to exceed the spending ceiling with a lower amount or for a shorter period) or it may not even be approved this year, given that we are already close to the parliamentary recess. If the agenda is left for 2023, it will have to be discussed again with the newly elected Congress, less aligned with the PT.

It's not just the practical impact of the PEC that moves the stock market. A good part of the money invested in the stock market is foreign capital and, seeing Brazilians themselves in fervent discussions about fiscal responsibility, managers of international funds, which generally have a small percentage of their portfolio in Brazil, tend to simply reduce their positions on the stock exchange. Brazilian society until the scenario stabilizes, instead of spending time trying to understand our political dramas in greater depth. We have recently seen international funds selling, at very low prices, shares in companies that may even benefit from the social spending that the new government plans, under the pure rationale of reducing exposure to Brazil. In times of turbulence, there are several market agents who behave in a less meticulous and analytical way than usually imagined.

Expectation for the yield curve

Another market assumption is that future interest rates will follow the current yield curve, as it reflects the best projections currently available. It's a reasonable assumption, but "best available projections" is something quite different from "optimal projections". In February 2022, we published a letter talking about the difficulty of predicting macroeconomic variables and showing the accuracy rate of forecasting future market interest rates. In short, she's pretty bad. In December 2020, the SELIC rate projection for 2022 was 4.5%. This illustrates how quickly the macro environment can change and completely thwart market expectations.

Our approach is to admit the uncertainty inherent in macro variables and stick to what we know with greater confidence: the current interest rate is high and is part of a temporary BCB action plan to combat inflation. The medium-term trend is mean reversion. Actions by the new government could prolong high interest rates, as we mentioned, but there is a long process before this materializes and, as we can see from the reaction to the PEC, both the government and Congress would have to bypass several relevant interest groups. . It's always possible, but it doesn't seem so likely to happen in the catastrophic proportions that the market fears.

Between the devil and the deep sea

From another point of view, it is worth considering whether it is better to have fixed income or stocks in the portfolio if the fiscal crisis scenario materializes. If interest rates rise because of the government's fiscal irresponsibility, this rise reflects the increased risk present in government bonds. The stock market may continue to decline, but investing in national fixed income does not bring so much security in this scenario.

Brazil has most of its debt in local currency, so the risk is not that it will default on the National Treasury, but that an extraordinary issue of currency be made to settle a portion of the public debt that becomes unpayable by normal means (despite to demand support from Congress, is a possible maneuver in extreme situations).

On the other hand, stocks may suffer from the downturn in the economy, but have a natural hedge against inflation and high real interest rates for long periods. The important concept to keep in mind is that a company that produces something useful for society will always have real economic value, regardless of the country's currency and interest rate. If the currency loses value, companies raise their prices and continue selling as long as there is demand for their products in the market. If the interest rate rises, the demand for credit will decrease to a point that forces interest rates to fall again. In an ultra-simplified way, this is the nature of the well-known economic cycles.

Investing outside Brazil could be an alternative, but it also has its problems currently. Current exchange rates are clearly not conducive to getting money out of the country and the global economy is not at its best either. United States and Western Europe, the markets that we generally consider as safe havens, are heading towards a recession caused by monetary policies to combat inflation very similar to the one adopted by Brazil, but we made this movement about 1 year earlier than these countries. That is, they may take longer than Brazil to grow again.

Anyway, there is no perfectly safe investment, with excellent profitability and liquidity.

focus on facts

Although it is impossible to predict the exact moment of reversal of the bearish cycle, we know that we are far from its peak. The risk that remains is that we will go through a few more bad years, but it is also necessary to consider the base from which we are emerging. We have just gone through years of severe economic problems caused by the pandemic. The return to normality, by itself, should make the next few years not as bad as the last.

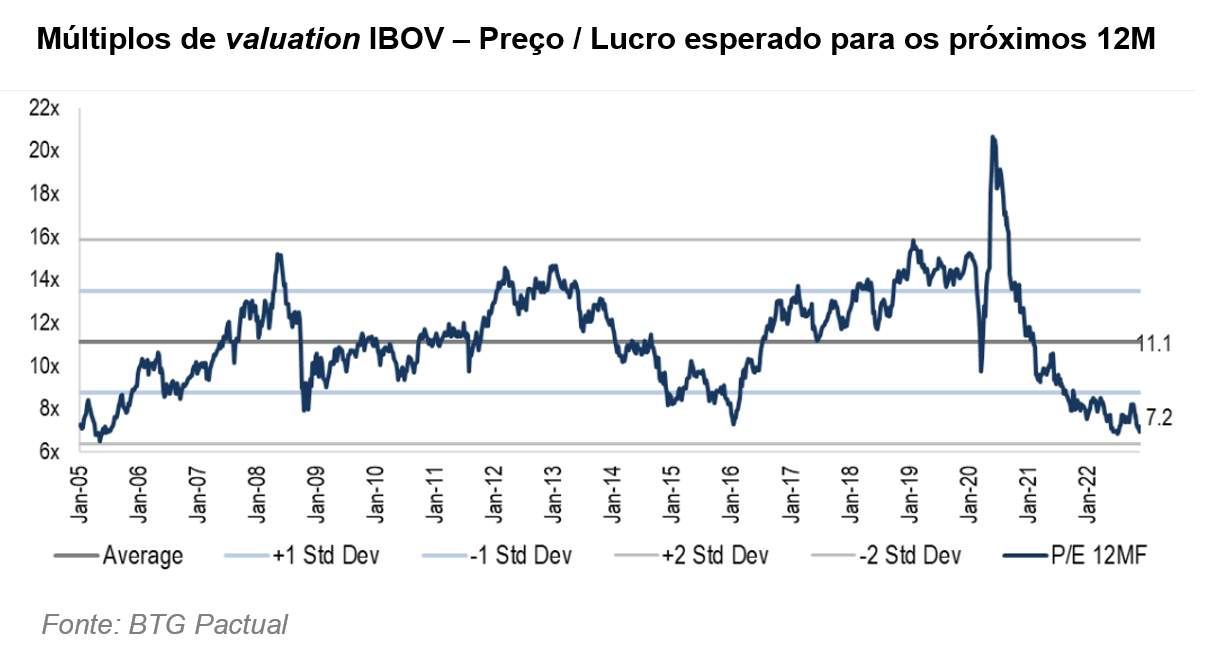

Also, today we are seeing quite rare stock prices. In our time operating in the market, we have only seen anything comparable in the subprime crisis, in 2009, and in the Dilma government crisis, in 2015. With prices at this level, some of our shares have the potential to double in value in the coming years in a scenario moderate macro. Even if the economy performs poorly, these stocks should still return considerably above the benchmark interest rate. Investments in the stock market will always have a risk of loss in catastrophic scenarios, but the current risk-return ratio seems to us quite favorable in selected stocks. The chart below makes it clear how cheap the stocks are: the stock's average Price/Earnings multiple is 35% below its average level.