Dear investors,

In the letter of June 2024, we explain why we decided to start investing outside of Brazil. We had already invested in two English companies and one of them was British American Tobacco (BAT). We recently sold this position with a return of ~31% in pounds sterling (~49% in reais) in just under a year.

It was a small investment, part of the proof of concept that it would be possible to apply our investment philosophy in other geographies with similar success to what we have had on the Brazilian stock exchange. With the always unfair point of view of hindsight, we should have invested more.

Whether for its value as a proof of concept or for how interesting it was to study the tobacco industry, which is full of controversies and has evolved in a very atypical way in recent decades, we thought it would be worth sharing the story of this investment thesis with you.

Brief history of the tobacco industry

Tobacco is native to the Americas and was brought to Europe in the 15th century by Christopher Columbus. In the following centuries, it became popular and became one of the most valuable products in global trade, rivaling sugar and cotton. Until the end of the 19th century, tobacco products were artisanal: pipe tobacco, cigars and snuff. The Industrial Revolution made mass production of the cigarettes we know today possible, and British American Tobacco, founded in 1902, was one of the first tobacco companies to achieve global reach.

Tobacco consumption peaked in the 1960s, when evidence began to emerge that there was a correlation between smoking and lung cancer. At the time, the tobacco industry responded by denying that its products caused any adverse effects and publicly fighting its accusers. Some time later, internal documents from large companies were discovered revealing that they were not only aware of the health risks but were also studying ways to make cigarettes deliver more nicotine, which increased smokers' addiction. The tobacco industry's lack of ethics during this period provoked a strong reaction from regulators and created a reputational stain that lasts to this day.

From the 1970s onwards, anti-smoking public policies were implemented around the world. One of the first measures was to ban cigarette advertising. As a result, it became virtually impossible for new companies to enter the industry. How can you launch a widely consumed product or expand your market share without advertising? The move ended up benefiting the big tobacco companies, which drastically reduced their advertising expenses and, even so, kept their sales volumes almost unchanged. The limited growth and the stigma surrounding the industry led to a major consolidation movement, and today the 5 largest tobacco companies in the world account for 93% of global sales volume.

Over 50 years of anti-smoking campaigns have been effective from a public health perspective. Today, only 10-151% of the population in developed countries consumes tobacco products, compared to over 401% in the 1960s. As a result, sales volumes have been falling and the traditional cigarette business is doomed to disappear or become a small niche market.

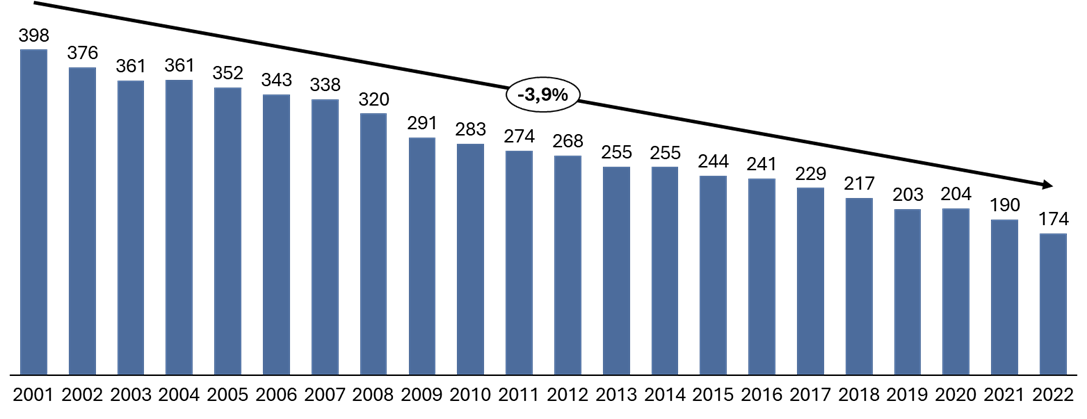

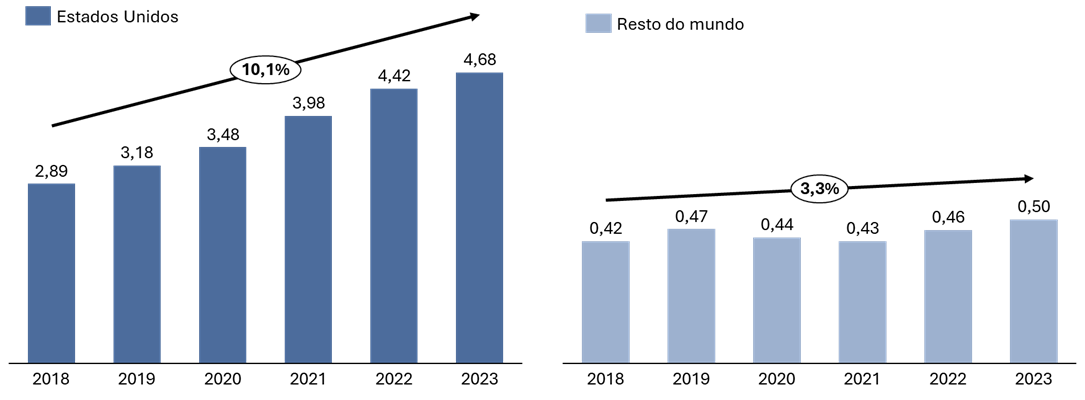

Cigarette sales volume in the United States (billions of units)

Source: Federal Trade Commission – Cigarettes Report

New generation of tobacco products

The tobacco industry has evolved to seek new products that maintain the side enjoyed by its consumers, but reduce or, ideally, eliminate the health risks. The result of this effort has been three new classes of products: electronic cigarettes (vapes), heated tobacco and nicotine pouches. Together, they are called NGP (New Generation Products). The general concept is to deliver nicotine, which produces the effect that smokers like, without emitting the byproducts produced by burning tobacco, which are carcinogenic. There is still widespread debate about how harmful these new products are to health. The prevailing opinion is that they are less harmful than traditional cigarettes, but that nicotine itself is not healthy to consume, so their consumption remains not recommended.

Interestingly, regulators have been more restrictive towards new products, especially vapes, than towards cigarettes themselves. The apparent motivation is the view that cigarette smokers are already addicted to the product and cannot be stopped from consuming it. If cigarettes were banned, this consumption would be shifted to the black market and would continue to exist illegally. However, regulators have the ambition to prevent young people from becoming new smokers and have acted against vapes in an attempt to curb the growth of this market.

Regulation varies greatly from country to country. In the United States, the sale of vapes is permitted, but the range of flavors is restricted to tobacco and menthol, under the argument that other flavors (e.g., fruits and sweets) are more appealing to young people. In Brazil, the sale of vapes is completely prohibited. However, in both markets, the bans have not been successful in inhibiting use. In the United States, 60-70% of the vapes consumed are illegal products. In Brazil, 100% is contraband. In both countries, illegal vapes are easily accessible. They can be purchased in local stores and even online.

The biggest problem with smuggling is the total lack of control over what is being sold. While legal vapes follow the requirements of regulators (in the US, the FDA), illegal products do not follow any standards. There are cases of contamination by heavy metals and nicotine concentrations much higher than those stated on the packaging of illegal products. The dilemma is: continue trying to combat vapes and prevent smuggling or reduce restrictions to shift consumption to legal products, where there is greater quality control? So far, the illegal market has only grown.

The possible future of NGPs

It is an undeniable fact that people like nicotine. Before the harmful effects of cigarettes became common knowledge, almost half of the population smoked. In underdeveloped countries, the smoking rate is still close to that. It is very likely that cigarette consumption will never return to what it was, for a good reason: the habit of smoking over decades reduces life expectancy by between 5 and 15 years (depending on the volume of daily consumption). But the discussion that NGPs now bring is: what are the harmful effects of consuming pure nicotine, through means not associated with burning tobacco?

There is still little research that separates nicotine consumption from traditional cigarettes, but there is evidence that the health risks of pure nicotine are much lower than the risks associated with burning tobacco. A study published in Public Health England (the UK health agency) states that vaping is 95% less harmful than cigarettes. If this assessment becomes a consensus in academic circles, would it make sense to continue investing in anti-vaping campaigns?

The discussion is sensitive, but it is clear that people often do not follow best practices for maintaining good health. For example, drinking alcoholic beverages is known to be harmful, but is widely accepted in most countries. Eating foods high in fat and sugar is even more common. Even though people are fully aware of the harm these products cause, most people do not want the government to monitor their personal habits and impose restrictions in the name of public health. In which cases regulatory intervention is appropriate will always be the result of a discussion that includes cultural factors, the degree of harm discussed, and the question of whether or not there is harm to third parties resulting from the activity. In the case of cigarettes, the considerable harm and the impact on the health of non-smokers exposed to cigarette smoke (known as passive smokers) were the main arguments for regulatory action. In NGPs, this logic will not necessarily hold.

There is currently strong regulatory action against NGPs, especially vaping, in several countries. We believe that the main driver is the association with traditional cigarettes and the distrust of big tobacco companies. However, we believe that what will define the final state of the NGP industry will be scientific evidence and popular opinion about the habit, not the original intention of the regulator. One case that reinforces this view is the history of Prohibition in the United States.

In 1920, the production and sale of alcoholic beverages was banned throughout the United States. The motivation was not health-related, but rather the argument that excessive alcohol consumption caused social problems, domestic violence, and crime. Initially, there was a decline in alcohol consumption, but the black market quickly developed and organized crime took over the production and sale of alcoholic beverages. After 13 years, the US state admitted the failure of the law and repealed it.

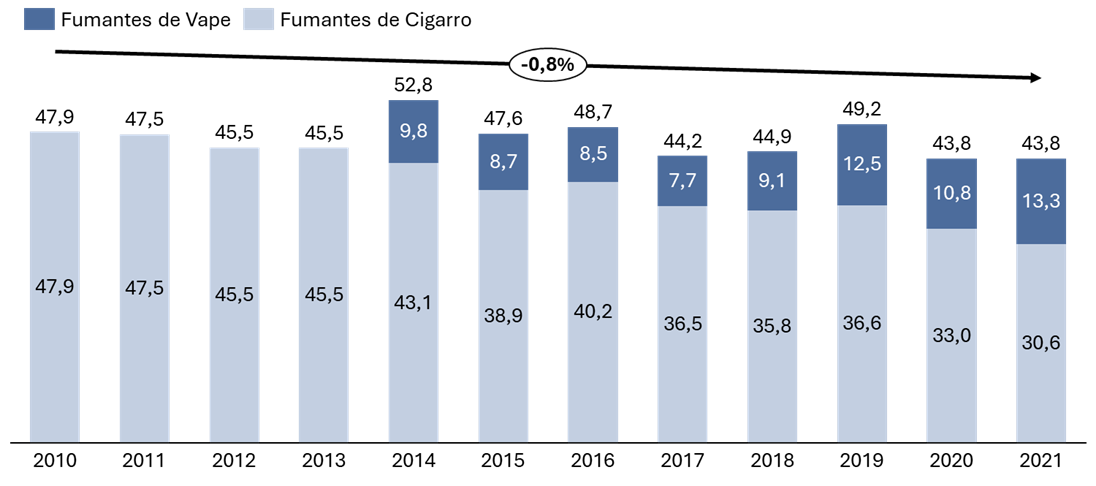

What we wonder is whether the history of vaping will not be an echo of Prohibition. As with alcohol, regulatory pressure has not been enough to curb nicotine consumption. The number of cigarette smokers has been falling, but new vape smokers are making up for the decline, and the total number of nicotine consumers has remained roughly stable.

Number of cigarette and vape smokers in the United States (millions)

Source: US. Census, lung.org statistics

If anti-vaping regulations are repealed in the future, the potential for NGPs to grow in the market is likely to be as high as cigarette consumption in the 1960s, when over 40% of the population smoked. In this scenario, Big Tobacco could expand rapidly, as they currently have the products and distribution channels to dominate this market.

Why do we buy BAT?

BAT is the world’s largest tobacco company, with ~30% of the global traditional tobacco market (cigarettes, cigars and snuff) and a similar share of the legal NGP market. The company operates in 180 countries with well-known traditional tobacco brands (e.g. Lucky Strike, Dunhill, Pall Mall, Kent, Camel) and in over 60 countries with major NGP brands (Vuse, Glo and Velo). It has annual revenues of GBP 26B, an EBITDA margin of ~45% (~GBP 12B), generates a lot of cash (~GBP 8B) and pays a generous dividend (~GBP 5B).

The financial results are excellent, but the future of the business is not clear. There are two product segments with very different dynamics within the company. Traditional products, mainly cigarettes, currently account for ~87% of revenue, but are in clear decline. New generation products, mainly vapes, account for the remaining 13% and have great potential for expansion when considering public acceptance, but there is strong regulatory resistance preventing this growth from materializing. It was necessary to analyze each of the segments separately.

The history of cigarette consumption confirms what we already know from direct observation: few smokers quit the habit. What has caused the smoking population to decline is that the number of new smokers is decreasing. In other words, sales volume falls as the smoking population ages, dies and is not replaced by new generations of equally large smokers. This demographic dynamic is inevitable, but slow. As a result, the rate of decline in cigarette consumption has followed a more or less predictable trajectory.

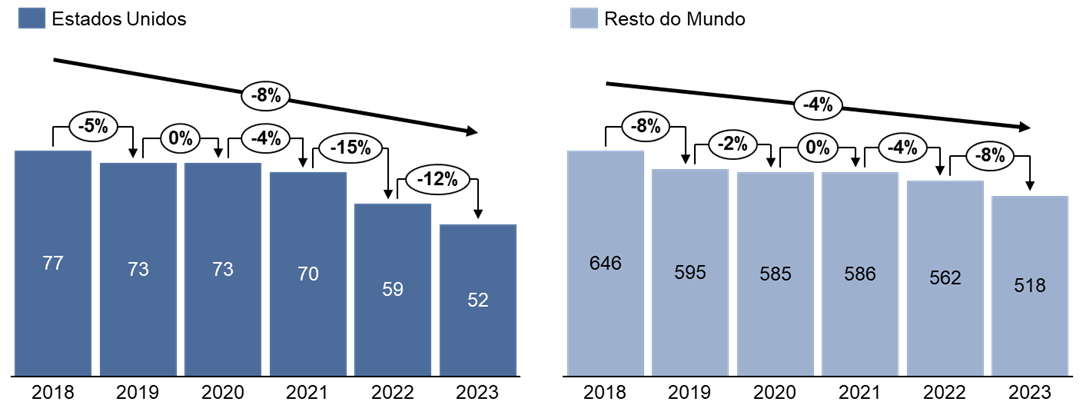

Number of cigarettes sold by geography (billions of units)

Source: BAT

Interestingly, BAT’s revenue and EBITDA from cigarette sales have remained the same despite falling volumes, thanks to a very simple strategy: raising the price of cigarettes to offset the decline in volume. It seems counterintuitive that this would work, but smokers have proven to be relatively price-sensitive and Big Tobacco has been applying annual price adjustments above inflation for several years. The effect has been to make the tobacco industry increasingly profitable, which would attract new competitors under normal circumstances, but regulatory constraints prevent this from happening.

Average price per pack of BAT cigarettes (USD per unit)

Source: BAT

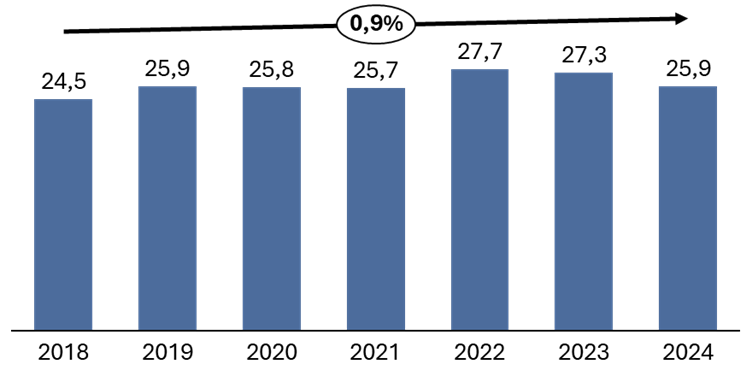

BAT Net Revenue (GBP billion)

Source: BAT

The issue of vapes is more delicate, largely because it depends on the regulatory stance. Even if the final scenario is the lifting of restrictions, as was the case with the Dry Law, the time needed for this to happen could follow the historical example and exceed a decade. Assuming that liberalization occurs, there is still uncertainty about what the profitability level of this new product segment will be, since in a more relaxed regulatory environment new competitors and possible price wars may emerge. The possible scenarios are so varied that the conclusion is not clear: the NGP segment may be worth very little or more than the entire BAT is worth today. Fortunately, at the time we decided to buy shares, it was not necessary to have a more precise view of this segment.

We added BAT shares to our portfolio in April 2024. The company's London stock market value was ~GBP 52B and our estimates indicated that, even with traditional cigarette revenues declining rapidly and NGP revenues stagnating forever, the likely return was in the order of 10% per year in sterling, a currency with historical inflation of 1-3% per year. Not phenomenal, but quite satisfactory for a somewhat pessimistic scenario. The stock was clearly mispriced. At this price, we got for free the options that cigarette sales would decline more slowly and that the NGP segment would grow. Not having to pay for the unpredictable part of the business made the purchase decision much easier.

Why do we sell BAT? A year after becoming a BAT shareholder, the landscape has not changed much from what we saw at the time of purchase. Traditional cigarettes continue to decline in key markets, while NGPs continue to see their growth impeded by regulatory barriers, and illicit products continue to meet the majority of demand. Regulatory developments around the world have been extremely slow and are still moving in the direction of being more restrictive for vaping, not less.

During this period, the share price has risen to a level that we consider more reasonable, and the logic that we are taking the existing option in the vape business for free is no longer true. Meanwhile, several Brazilian stocks remain quite discounted and we have practically all of our funds invested. So why not sell BAT to buy more shares in companies with higher return potential? We did that.

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.