In Memoriam: Daniel Kahneman

Dear investors,

Last week, Daniel Kahneman, a professor of psychology at Princeton and a pioneer in behavioral economics, passed away at the age of 90. Kahneman, a professor of psychology at Princeton and a pioneer in behavioral economics, questions the classical economists' premise that people always make rational economic decisions. For his academic work, he received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 and remained an influential thinker until the end of his life. In 2011, he published his book "Thinking, Fast and Slow," a global bestseller.

Kahneman's work gained great prominence among investors for mapping so-called cognitive biases: the human mind's tendency to deviate from pure logic and make poor economic decisions in certain situations. Every experienced investor recognizes how emotions can affect investment decisions and lead to undesirable outcomes. Therefore, understanding how human psychology relates to the investment process and striving to minimize the influence of cognitive biases on one's own decisions is crucial.

We've discussed this topic several times, but it's so extensive and relevant that there's always more to say. We've sought to share some of the knowledge developed by Kahneman, which has contributed enormously to our investment analysis processes.

Two systems in one mind

Our brains operate in two distinct modes. The first, which psychologists simply call System 1, is responsible for our quick, intuitive reasoning. It's automatically active all the time, requires no special effort on our part, and we have no voluntary control over it. This system recognizes familiar faces, coordinates our daily movements, perceives dangerous situations, and decides in fractions of a second how to react.

The other is System 2, responsible for the sophistication of the human mind that we properly understand as rationality, capable of processing information and abstract concepts methodically and logically. In contrast to this greater sophistication, System 2 is slow and requires conscious effort to focus on a specific problem for the full time necessary to solve it. This system performs mathematical operations, analyzes complex situations, and generally performs academic activities.

Each of these systems has its practical uses. System 1 handles most of our everyday decisions, which would be impossible to make using directly analytical methods. Imagine driving to work and having to explicitly calculate the best steering angle for each turn along the way. This is the best system for all cases where it makes sense to sacrifice precision for agility. It's enough that the steering wheel is approximately correct, and the speed allows for adjustments along the way, so an experienced driver's intuition works perfectly well in this situation.

System 2, on the other hand, is what allows us to transcend the level of animal intelligence and achieve uniquely human feats. Although slower and more difficult to use, it allows us to perform calculations sophisticated enough to launch a satellite with the precision necessary to place it in Earth's orbit, something virtually impossible to do intuitively.

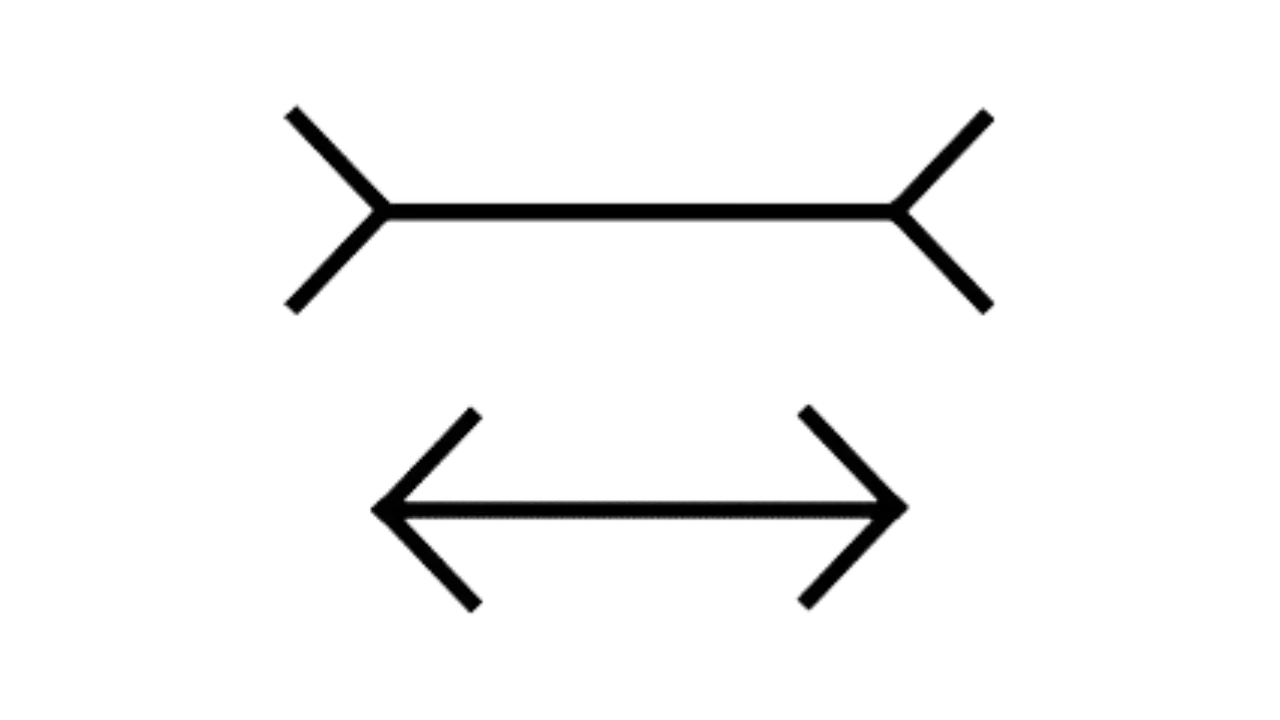

The problem with these two distinct modes of operation is that sometimes they both act simultaneously in conflicting ways. In other words, they reach different conclusions. This is the primary source of cognitive biases. The easiest way to understand the nature of a cognitive bias is through an analogy to optical illusions. In some situations, your brain misinterprets images. An example is the image below, where two lines of exactly the same length appear to be different sizes because of the shape of the arrows at their ends. If in doubt, feel free to measure the two lines.

System 1 perceives the lines as having different lengths. System 2 understands the error and accepts the proof that the lengths are equal after measuring both. Note that, even after confirming that the lengths are equal, you continue to see the lines as apparently different lengths. This is the nature of conflicts arising from cognitive biases. Sometimes your instincts point in a different direction than your own rational analyses, and proving that the analyses are correct doesn't change your instinctive perception, so making decisions based solely on the results of your analyses isn't as easy as it may seem. It requires conscious effort and a "vote of confidence" in the superiority of your System 2. This is where many investors fail, following their System 1 (which is always psychologically more comfortable) and ending up making poor decisions, even though they have the intelligence and knowledge necessary to develop a better plan of action.

Action of biases in investments

In theory, investment decisions should be made based on the probabilities of gain and loss implied by each investment opportunity. Whenever statistics favor the chance of gain, an investment opportunity would be advantageous. However, pure mathematics rarely predicts the decisions people actually make in real-life situations involving analysis of the probabilities of gains and losses. Consider the following scenarios:

Which of the alternatives would you prefer?

A. Win R$ 40 thousand for sure

B. Flip a coin. If it comes up heads, you win R$ 100,000. If it comes up tails, you win nothing.

The vast majority of people prefer to be certain of winning R$ 40 thousand, even though it is the mathematically less advantageous option, since the expected value of alternative B is R$ 50 thousand (50% x R$ 100 thousand).

Now, consider the reverse situation. Which would you prefer?

A. Lose R$ 40 thousand for sure

B. Flip a coin. If it comes up heads, you lose R$ 100,000. If it comes up tails, you lose nothing.

Now, would you rather flip the coin and rely on luck? Most people prefer alternative B in this situation. Note that the mathematics involved are very similar, so there's a logical inconsistency between preferring alternative A when the problem involves gains and alternative B when the same problem involves losses. However, people consistently make decisions this way.

Studying this type of inconsistency in decisions involving probabilistic analysis, Daniel Kahneman and his research partner, Amos Tversky, developed Prospect Theory. The main finding is that people experience the impact of gains and losses differently: losses are felt more intensely than gains of the same value. Given this distinct perception of gains and losses, people are instinctively more risk-averse in situations involving potential gains and accept greater risk when the situation involves potential losses.

Anyone who has invested directly in stocks has probably felt the effects of this bias in the following situation: when you buy a stock and it rises significantly, your instinctive response is to sell it to capitalize on the profits you've made so far. When the stock falls, your instinct is to hold on until the price returns to at least the value you paid.

Another bias mapped by Kahneman and Tversky is that the perception of economic value is not only associated with the absolute value itself, but also with the variation that value represents in the total gain or loss. The greater the gain or loss, the less likely you are to feel the impact of an additional gain or loss. For example, if your profit on an investment goes from zero to R$ 50,000, your sense of gain will be much greater than if you already have a profit of R$ 500,000 and it increases to R$ 550,000, even if the amounts of the additional gains are exactly the same.

Nos investimentos, esse segundo feito potencializa o mal do primeiro. Quando a ação sobe, você tende a dar menos valor para a chance de ela subir mais um pouco e prefere vender logo. Quando ela cai, você tende a enxergar um mal menor em vê-la cair mais um pouco e prefere continuar na esperança de que volte a subir. Assim, por vezes, investidores vendem cedo demais as boas teses de investimento – e, comumente, veem a ação subir muito além do preço da venda precipitada – e continuam segurando ações que já não têm mais boas perspectivas de ganho por mais tempo do que seria razoável, na esperança de evitar a dor psicológica de cristalizar o prejuízo.

These are very specific examples from the long list of cognitive biases mapped by Kahneman. For those who want to read a little more on the subject, we discussed some other biases relevant to investment decisions in our letter.The flaws of the human mind”, from April 2022. However, the best source is the book “Thinking, Fast and Slow” itself, a read that is not only useful, but also quite enjoyable.

How to deal with biases in investments

We've already discussed that, just as optical illusions are inevitable, it's impossible to temporarily turn off your System 1 to eliminate the cognitive biases it causes. Even Kahneman, after decades of dedicated study, admitted he hadn't been able to eliminate his biases. So, what can be done to avoid cognitive errors in investment analysis? Here, we'll combine Kahneman's recommendations with our own experience.

Identifying the effects of cognitive biases in real life is less obvious than it might seem at first glance. When an important decision is to be made, those involved are typically focused on the decision itself, rather than on the potential cognitive errors their own minds may encounter while considering the matter. Thus, mitigating the likelihood of cognitive errors requires a series of measures.

The first step is to study the cognitive biases that can interfere with investment decisions and the situations in which they typically manifest, as it is very unlikely that you will notice their manifestation without having a clear picture of the behavioral pattern you are seeking to identify.

The second step is to make a conscious effort to remain vigilant for potential biases during real decision-making processes. Your memory won't always be complete and reliable enough for you to identify the biases that tend to influence your own decisions by recalling past situations. This exercise is easier to do as a team, as biases are often more easily identified by an outside observer than by yourself. Each person is more sensitive to certain biases, depending on their personality, and knowing what they are helps greatly mitigate their effects.

The third step is to structure a formal investment analysis process that facilitates maintaining the rigor and discipline necessary for each decision to be as rational as possible. An excellent practice is to record all the relevant points of each analysis in writing. This not only helps maintain a history of analyses and allows for the evaluation of successes and failures in retrospect, but also enhances structured reasoning skills. Just as it is much easier to perform mathematical operations on paper than in your head, it is easier and more assertive to perform complex qualitative analyses by writing down each step of the reasoning than by working purely from memory.

Even with a well-structured analysis process, it requires constant attention to execute it with discipline. Because System 2's dominance depends on conscious effort, simply neglecting it can allow System 1 to take over and introduce bias into reasoning shortcuts that, at the time, probably seem perfectly appropriate.

The target that no one saw

Kahneman's contribution was so relevant because it brought clarity to a field rife with subjectivity and conflicts with classical economic doctrine. The premise that intelligent, qualified people would make economic decisions purely rationally has survived for so long in academia because it is, in fact, quite reasonable. What's surprising is the realization that, in reality, things are not that way.

The very notion that our instincts can lead us to wrong decisions isn't obvious. Popular culture goes in the opposite direction, portraying intuition as something that trumps rationality and points us in the right direction in the most difficult moments. In fact, the stereotype of a great investor in movies is one who follows their instincts with courage and boldness, making big bets that quickly bring them fortune. The great investor is usually almost the opposite: one who doubts their own instincts, analyzes each opportunity methodically, and avoids letting their emotions influence their decisions as much as possible.

“Todos nós pensamos que somos muito mais racionais do que realmente somos. E achamos que tomamos nossas decisões porque temos boas razões para isso. Mesmo quando é o contrário. Acreditamos nas razões por que já tomamos a decisão.” — Daniel Kahneman