Dear investors,

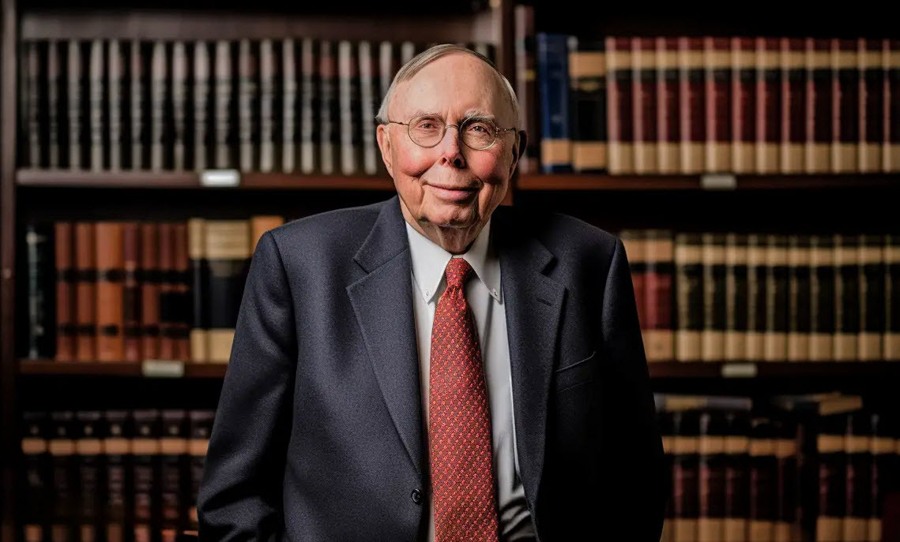

Last week, in a matter of minutes, news of the death of Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett's partner at Berkshire Hathaway, who would have turned 100 years old, spread throughout the financial market. Fame comes not only from the size of Berkshire, today valued at around USD 800 billion, but from the fact that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger inspired a legion of investors attracted not only by Berkshire's success, but by the philosophy of life followed and preached. for them.

While Buffett fits more into the stereotype of a businessman, diplomatic in his expressions, Munger was more transparent and direct, not only to make his founding values clear, but also to openly criticize what went against them.

This mixture of honesty and intellectual generosity meant that Munger, even though he was not so adept at public demonstrations, left a vast legacy of knowledge in the recordings of the annual meetings of Berkshire Hathaway and the Daily Journal (the latter led by him), in a series of articles and interviews.

In this letter, we will rescue some of Munger's lessons that, over time, had the most impact on the formation of both our investment philosophy and our own ideals in life. For anyone interested in delving deeper into the life and philosophy of Charlie Munger, we recommend reading the book Poor Charlie's Almanack.

The sources of human errors

Munger said that, early in life, he was struck by the fact that so many obvious mistakes were made by people, even those who were intelligent and should be able to recognize the irrationality of their actions. This led him to seek to understand what motivated such failures, and what he should do to avoid falling victim to the same fate. Throughout his life, he ended up becoming a “collector of stupidities”, his simple way of referring to the anecdotes about irrational actions that came to his attention.

The topic is less trivial than it might seem. In the 1970s, the first academic studies on what became known as cognitive biases appeared, carried out by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. In parallel with the emergence of this academic area, now reasonably known among investors, Munger had developed his own system for identifying cognitive biases. Several of his principles are condensed in a lecture given at Harvard University, entitled “The Psychology of Human Misjudgment”.

This knowledge has twofold uses. The first is to use the cognitive bias map to interpret the probabilities of how people may act when faced with investment and business decisions. The second is to understand which of them you yourself are subject to and learn to avoid them, to improve the quality of your own decisions. In our experience, biases affect each person differently, depending on their personality. Therefore, an initial stage of self-analysis is necessary, to understand in what types of situations specific biases can influence you, and eternal self-discipline to prevent possible resulting errors. The ideal to be pursued is to be purely rational in each and every decision.

“People are trying to be smart. All I’m trying to do is not be an idiot, but it’s harder than most people think.” – Charlie Munger

Mental models

Avoiding mistakes is already a good first step, but Munger argued that it is possible to greatly expand our cognitive capacity by cultivating a series of mental models that serve as a toolbox for interpreting the reality of the world.

The concept of mental models is inevitably abstract: they are archetypal ideas that function as shortcuts to facilitate the understanding of certain situations, as if they were pre-processed deductive chains that can be quickly retrieved to compose more complex lines of reasoning. For example, in economics, the notion that large-scale industrial operations tend to have lower unit costs is a mental model that can be immediately recalled without having to go through the whole line of reasoning that deduces why this effect happens.

The main point of Munger's philosophy is that having few mental models is not enough. Reality is complex and multiple angles of analysis are generally needed to understand, for example, how a business can develop over time. Furthermore, reality does not respect the divisions between areas of knowledge created by academics, so it is common that the mental models required to understand a business are not only related to economic theories, but also to several other areas (psychology, politics, physics, chemistry, biology, etc.). Therefore, an investor must be willing to study whatever is necessary to understand their object of analysis, regardless of which academic area the knowledge of interest is in.

The risk of being too specialized is losing breadth of vision. With his characteristic humor, Munger illustrated this risk by saying that “to the man who only has a hammer, everything looks like nails”.

“What you need is a network of mental models in your head. And with this system, things gradually fall into place in a way that expands cognition.” – Charlie Munger

Circle of competence

Since knowing everything is a utopian ideal, despite the willingness to overcome any artificial barriers created between academic departments, it is important to be realistic about your own ability to analyze a given case. In other words, always start by judging whether your current knowledge is sufficient to analyze a specific investment thesis. This boundary of how far your own knowledge reaches is what Buffett and Munger called the circle of competence.

For investors, the first recommendation is to never leave your circle of competences. Instead of seeking to develop opinions about anything, it is safer to select only those investment opportunities that you have a very deep understanding of and form more assertive opinions about them. The rest of the opportunities, which are outside your circle of competences, should be avoided, due to the risk of misinterpretations caused by your own lack of knowledge about the specifics related to the case.

Defining your own circle of competences is an exercise in humility, but not in conformity. The boundaries of your knowledge are not fixed, and can be continually expanded as you dedicate more and more time to studying new topics. Munger said Buffett's trick to being so successful is that he never stopped learning new things. Even after being extremely rich and already quite old, he continued studying and learning.

“Being aware of what you don’t know is more useful than being brilliant.” – Charlie Munger

Slow debugging

On one occasion, Munger criticized the modern trend toward increasingly shorter attention spans. Going in the diametrically opposite direction, he attributed much of his success to his ability to maintain focus on a subject of interest for long periods of time, as long as was necessary to understand in depth and completely absorb each new piece of knowledge.

Despite the apparent lack of agility that this approach can bring, investing the time necessary to fully master new concepts allows you to react faster to situations that continually arise. Buffett once said, “Charlie can analyze any type of business faster and more accurately than anyone. He sees any possible weakness in sixty seconds.” The story illustrates the result of a life dedicated to the patient and constant purification of countless mental models.

Munger also said, “Consider a simple idea seriously,” noting that simplicity is sometimes the result of long, hard work to understand the deep truths of the world and condense them into a format suitable for memory. Generally, people ignore the effect of simple concepts because they believe they are too trivial to explain high-impact situations, but it is common for widely known factors to be the most determining variables in business scenarios.

The value investing philosophy itself is quite simple: look for predictable and resilient businesses, wait until you have the opportunity to buy them cheap and have the patience to wait until the investment generates results. However, even though this simple and widely proven successful method exists, a large part of the investing public continues to look for new miraculous investment methods.

“I didn’t succeed in life because I was smart. I was successful by having long attention spans.” – Charlie Munger

Independent thinking

Seeking to personally understand the principles and logic behind each opinion, rather than simply accepting that the most popular view is correct, is a general concept valid for any field, but especially important in the field of investments. Inevitably, the greatest investment opportunities will be related to cases in which an investor is, at the same time, correct and contrary to general market opinion. The inevitability comes from the fact that, if the market had the same opinion, the price of the analyzed asset would already reflect expectations and would no longer offer exceptional returns. Therefore, an investor who aspires to have above-average returns needs to be willing to maintain his convictions in dissonance with the majority of his peers.

The caveat here is that going against the market, quite simply, is not a recommended strategy. In most cases, the analyst and investor community is correct and, by default, always acting in the opposite direction tends to produce bad results. The goal should be to identify the few situations that you are able to understand better than average and act with conviction when the market is contrary to your own informed view.

“Everyone is wrong except Charlie.” – Charlie Munger

Discipline and patience

Finally, we emphasize that none of the lessons summarized here are tricks or shortcuts that make investing easy. Despite the simplicity of the recommendations, their implementation requires constant effort over long periods. This is yet another mental model that can be easily incorporated: true human excellence is achieved through decades of dedication to self-development, and not through magical methods that allow quick results. Developing vast knowledge depends on thousands of hours invested in accumulating information in memory and human intelligence requires a certain methodological polish to be used to its maximum potential.

Therefore, the best investors will naturally be those who adopt good methods and dedicate their lives to studies and constant self-development.

“To get what you want, you have to deserve it. The world is not yet a crazy enough place to reward a bunch of undeserving people.” – Charlie Munger

We are deeply grateful to Charlie Munger for his shared knowledge and life example. May his memory and philosophy remain alive for generations and generations of investors.

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.