Dear investors,

In April, the IBOV fell by 10.1%. Prior to that, the index had risen by 17% from the start of the year to its peak on April 1st. The price of our Ártica LT FIA share has also dropped by 6.1% in the last month and has varied a lot since the beginning of the year, so we'll dedicate this letter to a theme that couldn't be more current: falls in share prices.

We have already mentioned on other occasions that we go through periods of low prices in a more positive mood than the market in general. Our motivations for this stance seem almost obvious once understood, but they receive so little attention that we imagine it would be helpful to our readers if we spelled them out in more detail.

The Paradox of Multiples

When we buy shares, there are only two ways to get some money back: i) receive dividends (or interest on equity) and; ii) sell the shares. The volume of dividends distributed depends on how much profit the company generates over time and the price at which it is possible to sell the shares depends not only on the profit generated, but also on the expectations that the market has regarding growth and future profitability of the business that, in a simplified way, we will assume to be represented by the proportion between the valuation assigned to the company and the value of its net profit, that is, the company's P/E (Price / Earnings) multiple.

So, to have good returns, we should want our companies to generate as much profit as possible and their P/E multiple to increase as much as possible, right? Think for a minute what the flaw in this reasoning is…

Evaluating only the return on a specific investment, this logic works perfectly. However, what we are looking for is not the maximum return on a specific investment, but the maximum return on all our assets throughout our lives. With this objective in mind, the desire remains that our invested companies generate the maximum possible profits, but the second factor is inverted: the smaller the Price / Earnings multiple becomes, the better, assuming that the reason for the drop is not connected to some setback in the investee company. We will explain why.

The cheaper the better

In a first moment, when we start buying shares of a certain company, obviously we should want the share price to be as low as possible in comparison to the company's ability to generate future financial results (simply put, the lowest P/E multiple possible) . As long as we have capital available to buy more shares, this logic holds and we should want the share price to fall over the course of our purchases.

This point generates some psychological discomfort in many investors, as seeing the stock being bought falling causes the feeling that the first purchases were made at a high price. However, assuming that the first purchase decision already considered the price attractive in view of the company's expected cash generation, the fall in the share price makes the investment opportunity even more attractive and should be seen with good eyes by investors.

Having pacified the point that buyers prefer low P/E multiples, the next argument is more subtle. Even after allocating all available capital, being unable to continue buying, a long-term investor should still consider himself as a potential buyer and prefer low P/E multiples, as invested companies will pay dividends over time and dividends received will need to be reinvested by buying more shares.

In general, when multiples of valuation of listed companies are below average, the moment is opportune to invest in stocks, as the expected return on purchases made at attractive prices is naturally higher than average.

to unbelievers

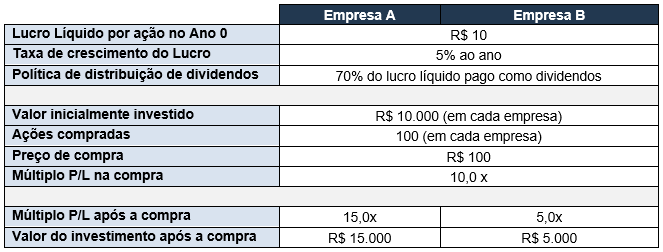

If you're not convinced, consider the following example, where an investor buys 100 shares of two identical companies, with only one detail different: Company A's valuation rises by 50% shortly after the purchase and Company B's falls by 50%.

Assuming that the valuation multiple, changed shortly after the purchase, will remain the same forever, and that the investor will use the dividends received to buy more shares in the company that distributed them. companies.

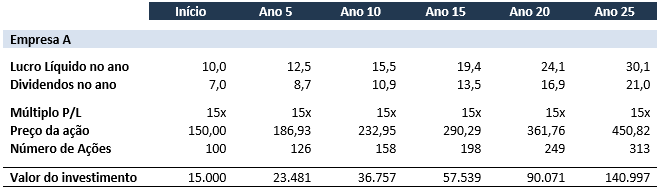

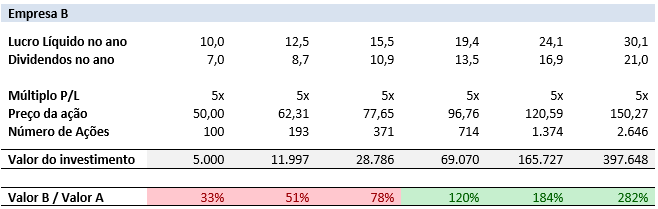

Although, in Company B, the investor starts with a loss of 50% and an amount equivalent to 1/3 of the shares in Company A, he is able to buy more shares of Company B with the dividends distributed by it, due to the valuation much lower. Over time, Company B becomes a better and better investment and outperforms Company A.

It is impressive how, even with such a marked difference in multiples, in the long term the benefit of buying more shares at attractive multiples, using the dividends of the business itself, outweighs the benefit of a higher valuation multiple.

The secret is to buy cheap

The conclusion of the above analyzes is obvious: buying cheap is good. But there is a less obvious continuation to this statement: buying cheap is always good, regardless of future price movement. If the stock becomes even cheaper, we fall back on the example of Company B. Furthermore, it is not feasible to predict short-term price movements, which makes any purchase or sale policy based on the opinion of market price movements ineffective. on a scale of months. For these reasons, we adopted the practice of buying shares whenever we found good deals at attractive prices, ignoring the “market mood” at the time.

Note that there is a vital point of attention in this approach. To buy cheap stocks, you need to know which prices are cheap. We are using the P/E multiple in the examples in this letter, but this is a loose reference point on the valuation of a business. Assessing how much a company is worth is always more complex than looking at the historical P/E multiple and comparing it to the current P/E multiple. In essence, each investor must estimate what the financial results of each company will be in the long term and discount the cash flow generated by each business at a rate of return that he deems appropriate, only then having a value reference against which the price of the action can be compared and considered as cheap or expensive.

By guaranteeing a good purchase price, the investment will only have a poor return if the future of the invested company is worse than estimated at the time of purchase. The instantaneous price of a share receives exaggerated attention, due to the fact that we want to quantify the value of investments at all times, but it only matters at the time of sale, and selling is not a mandatory act. We can keep the shares in the portfolio for as long a period as is convenient for us.

If stocks get expensive

When an investee company reaches levels of valuation high, we started to consider the possibility of selling it. However, the reason for the sale should not be the share price itself, but rather the opportunity to reallocate the capital invested in businesses with expectations of better returns. That is, it only makes sense to sell when an investment opportunity is identified with an additional expected return sufficient to cover the transaction costs of this reallocation of resources.

Note that this need to reallocate capital invested in a company that has become expensive is a good problem to have, as the reallocation is completely optional. If we do nothing, the expected return should still be approximately what was estimated at the time the shares were purchased, assuming the invested business has not changed much.

That's why we place so much emphasis on the importance of buying good companies at attractive prices. The quality of the business ensures that it is long-lasting and profitable, and the low purchase price ensures a good return regardless of the multiples of valuation in the future.