Why doesn't Brazil grow?

Dear investors,

In our last letter, we discussed ten crises Brazil has faced since the Plano Real and how the stock market performed in each of them. The conclusion of this summary echoes what we've learned in 12 years of investing here: Brazil is a good place to make money in the stock market not because of the strength of the national economy, but because stock price volatility is greater than that of our economy, generating excellent investment opportunities.

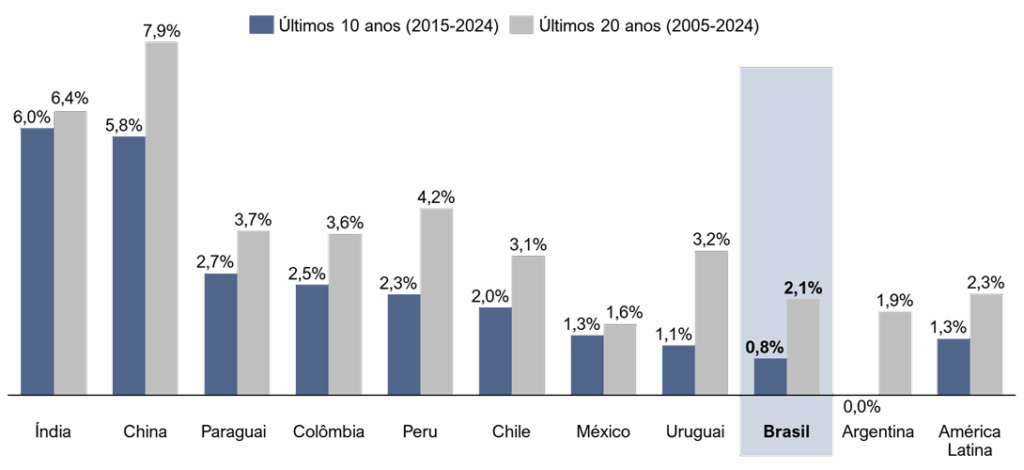

We can't complain about the returns we've seen in this situation, but we still share the frustration of most Brazilians: a persistent feeling of wasted potential. Why isn't a continental nation, brimming with natural resources and without major geopolitical problems, developing? Comparisons with other emerging countries reveal how far we've fallen behind, especially in the last decade.

Average GDP growth

Source: World Data Bank

The direct causes are well known. We have a profound education problem. Brazilian productivity hasn't advanced for decades. We experience near-constant political crises. But what are the root causes of these problems? Why have other countries been able to solve these problems and we haven't? Without claiming to provide definitive answers, we will share our perspective.

The educational problem

The most superficial discussions about education in Brazil blame a lack of resources. The more sophisticated ones pay greater attention to teaching methods, institutional governance, and international best practices. It's rare to hear anything beyond that, but we seem to have a third layer, closer to the heart of the matter and related to Brazilian culture.

Saint-Exupery wrote, "If you want to build a ship, don't gather your people to give them orders, explain every detail and where to find everything... If you want to build a ship, awaken in the hearts of your people the desire for the immensity of the sea." Human performance depends first on motivation and then on method. An operation with well-designed rules and processes, but disengaged people, is unlikely to be more than an inefficient bureaucracy. The first step to a quality education is to truly value and desire knowledge. It seems obvious, but that's not what we see in our country.

The average Brazilian wants a diploma, understanding it's necessary to apply for certain positions, but cares less about the actual knowledge it's supposed to certify. A widely known fact corroborates this assertion: most Brazilian students cheat on exams, the infamous "cheating," so widespread that it's no longer morally condemned. The blame isn't solely on the students. In part, this disdain for academic pursuits stems from the poor correlation many syllabuses have with real life. Students don't see how classes will help them succeed, interpreting them as a waste of time, and ultimately developing a prejudice against studying in general. In part, it stems from a world where a 15-year-old influencer suddenly explodes on social media and starts earning multiples of the salaries of a doctor, lawyer, or engineer with decades of experience, making it seem like pursuing traditional careers is a lack of wisdom. There's no simple solution, but at least two aspects of our culture could be improved.

The first is to abandon the immature ambitions of quick and easy success that seem to have become the modern norm. It's true that successful 15-year-old influencers exist, but the average salary of all aspiring 15-year-old influencers is certainly far lower than that of doctors, lawyers, and engineers. Just as playing the lottery weekly is a poor plan for getting rich, career strategies based on extreme exceptions tend to backfire. Mature ambition is the "American Dream": the conviction that anyone can succeed in life through determination, hard work, and initiative. Studying and training until you become proficient at something useful is still a wise plan.

The second is to reestablish the understanding that knowledge has practical utility and, therefore, is immensely valuable. Humanity does not seek knowledge out of bureaucratic demands or academic pomp, but rather is motivated by problems and ambitions of epic proportions. Those responsible for great intellectual advances are the true heroes of the human race. Everyone has heard of Aristotle, Isaac Newton, and Albert Einstein. Aristotle lived ~2,400 years ago. The fashionable celebrity who receives the most popular admiration today will hardly be remembered in the same way 24 years from now. Intellectual splendor is one of the highest ambitions within human possibility.

How to change is the big question. We don't see any tricks or shortcuts. Those who spread a nation's culture are public figures and those in positions of power in society. China's Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, makes a point of cultivating his image as a professor and is called Ma Laoshi (Professor Ma). This case illustrates the cultural gulf between China and Brazil, which seems to contribute to their respective levels of economic success. If our elites dedicate more time to cultivating erudition, the rest of the population will tend to follow suit.

The efficiency problem

Stagnant productivity is a different problem. Increasing economic efficiency is a clear and perpetual objective in the business world, so the cause isn't a lack of motivation. Everything indicates that much of the problem stems from dysfunctional rules in Brazilian society: the tax system, the judicial system, and multiple interventions in the economy. However, the theoretical solutions to these problems are reasonably well-known. The OECD, an international organization that seeks to improve economic and social well-being worldwide, has conducted dozens of studies and publishes detailed reports with a series of best public management practices. Even so, many of these suggestions are not implemented here. The reason behind this seems to us to be linked to the prisoner's dilemma trap that manifests itself on a national scale.

In the classic dilemma, two accomplices in a crime are arrested and pressured to confess. If both remain silent, they face one year in prison. If one confesses and the other doesn't, the one who confessed goes free and the other is imprisoned for 10 years. If both confess, they jointly face five years in prison. The theoretical best solution would be to cooperate and face one year in prison, but, fearing being the worst off, both end up confessing and face five years. The rules of Brazilian society are determined by a similar dynamic.

Taking Brazil's fiscal problem as an example, the best solution would be to simply cut spending. This is what people do at home or in companies when the incoming money is insufficient to pay the bills. The government clearly knows this and fully understands the alternative. It doesn't pursue this path because it's not what society truly demands. In rhetoric, most people may even advocate spending cuts. In practice, most pressure the government to obtain advantages for themselves, which directly imply public spending. Ordinary citizens want social benefits and income tax exemptions. Business owners want differentiated tax rates for their sectors and various subsidies. Together, these pressures from specific interest groups inflate public spending, distort the rules, and create a dysfunctional tangle. The main consequence is the misallocation of capital in the country.

The free market principle holds that the economic system is too complex to be centrally controlled, and therefore, it is more efficient to allow the free fluctuation of prices, formed by the balance between supply and demand, to generate the necessary incentives to optimize the functioning of economic activities in general. Companies that efficiently deliver products or services valued by society, compared to their competitors, will be profitable and prosper. Inefficient ones are doomed to bankruptcy. This dynamic should guide the best use of the country's available resources to produce as much of what society desires as possible. When the government begins to legislate different rules for each sector, this principle of market self-regulation ceases to be valid. With subsidized financing and differentiated tax rates, inefficient companies can survive and grow more than efficient businesses, but they receive no government benefits. And there goes the desired increase in national productivity.

This issue won't be resolved by private entities, as there's no incentive for anyone to give up lobbying first, there's no coordination among all parties to negotiate an agreement where equitable rules are adopted simultaneously, and implementation necessarily passes through Congress. The government itself needs to lead the reforms, and the private sector's role is to fairly evaluate whatever is proposed and push for equality, not for benefits.

We had the opportunity to make significant improvements in the recent tax reform, but we took a more timid step than intended. It seems to us that this isn't the politicians' fault. The original proposal was excellent, but it was distorted by pressure from multiple groups, and the approved law introduced a series of special regimes, differentiated conditions, and the like. The analogy with the prisoner's dilemma is clear: by acting individually, all sectors will end up subject to a worse set of rules and will have their long-term growth potential compromised by the poor performance of the national economy. A solution requires joint goodwill from both the public and private sectors.

The political problem

Here, we elect both the president and senators and representatives, affiliated with one of the 29 parties, by direct vote. This political arrangement, called fragmented multiparty presidentialism, is less common than one might imagine. Countries with similar regimes are concentrated in Latin America and Africa, and even within this group, Brazil is an extreme case of party fragmentation. No other developed country adopts the same system.

It's as if we had a huge company where all the executives are at loggerheads. Governing is already inherently difficult, and this structural misalignment among the politicians involved in the administration complicates the situation even further. With so many active parties, the president's party rarely has a majority in Congress, and agreements with other parties are necessary to form a coalition and govern. Even so, there are frequent impasses between the Executive and Legislative branches, and any proposals for major changes end up being diluted during negotiations to approve measures in Congress. For better or worse, change in Brazil is slow and gradual.

Meanwhile, most developed countries have a parliamentary system, a political system in which the head of the executive branch, the Prime Minister, is indirectly elected by members of Parliament (equivalent to Congress in presidentialist countries). Alignment between powers is guaranteed, as Parliament can call a vote at any time to recount the number of votes for or against the current Prime Minister. If the majority of votes are against, the Prime Minister resigns and Parliament elects a new one, or Parliament is dissolved and new elections are called to form a new Parliament. In other words, one of the two branches of government is replaced, and alignment is restored.

One alternative is bipartisan presidentialism, the best example of which is the United States. The existence of only two predominant parties simplifies the issue of governability. Either the president has a majority in Congress and implements his or her own party's plans, or he or she does not and is forced to negotiate with the other party. Alignment between the branches of government is not guaranteed, but negotiating with just one opposition entity is much simpler than multilateral negotiations. There is also semi-presidentialism, a hybrid system in which a president and a prime minister share executive power. France, Portugal, and some other countries are semi-presidential.

Changing Brazil's political system is far from simple. Reform would likely require a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution, a process that opens a Pandora's box and might be best postponed until the population has a little more political maturity. In any case, "a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step," and it seems appropriate to begin by discussing the existence of this structural problem.

Rise of populism

This isn't just a Brazilian problem. The entire world is experiencing a new wave of populism, driven by the immediacy characteristic of modernity combined with the communication style of social media. The quality of public debate has always had room for improvement, but it's clearly deteriorating. Electoral contests have become "meme wars," in which digital content quickly reaches millions of views and shapes public opinion.

The issue is delicate because the problem isn't the style of communication itself. Symbolic elements have always been part of political disputes and sometimes synthesize legitimate messages that many lack the eloquence to express clearly. The problem is that this viral communication is used as a tool to leverage populist discourse, which always spreads faster than its cure: increasing the population's educational level.

It's as if we wanted to elect a school principal through student votes, and while one candidate tries to convince students that extending study hours and maintaining rigor is best for them in the long run, another simply distributes stickers with the message "More vacations, fewer tests! Students deserve respect!"

Despite the problem, we do not believe that any attempt to control communication is adequate. Freedom of expression is a fundamental pillar of democracy for good reasons, and abandoning it can lead to worse problems. The fact that the world has oscillated between populism and austerity for millennia indicates that there is no definitive solution. A return to austerity comes when populist measures fail and people are forced to understand certain issues through the imposition of practical reality. What we can do is try to spread a minimum level of political awareness and be careful not to support initiatives that become populist traps for all parties. One of these is the broad distribution of benefits we have in Brazil.

Today, 12 of Brazil's 26 states have more Bolsa Família beneficiaries than formally employed workers, a result of actions from both sides of the political spectrum. It's become common practice for workers to no longer want CLT jobs because they earn more working informally and underreporting their income to receive government benefits. This arrangement is flawed on multiple levels. It reduces the availability of labor for Brazilian industry and shifts people's useful time to less productive informal jobs, which only pay off economically when the government collects money from the formally employed population—since informal workers don't pay taxes—and redistributes it to the unemployed or "underemployed." At the same time, the popular imagination is imprinted with the idea that it's advantageous to conceal income in government declarations, receive benefits, and work flexible schedules. Instead of encouraging a work ethic and regular dedication to permanent positions within a productive economic system (companies), we encourage low-productivity, independent micro-initiatives and the practice of fraud against the federal government.

It's not an easy trap to dismantle. Any party that opposes it will be doomed to lose the elections. There's still a risk that we'll see benefits being increased during election periods, in populist campaign auctions. The most likely solution is to wait for the value of benefits to be eroded by inflation or for some external crisis to be used as justification for faster adjustments.

Is there hope?

Singapore proclaimed its independence in 1965, after being expelled from Malaysia in a political maneuver aimed at destroying the ruling party in Singapore and subsequently receiving the city-state back under total subjugation. The small country of ~2 million inhabitants had a per capita GDP of ~$500,000, a population divided into three main ethnic groups that conflicted with each other, spoke more than 10 different languages, and ~35% of the population was illiterate. Today, Singapore's per capita GDP is $85,000, and the country leads the international education rankings (PISA 2022) in three categories: mathematics, humanities, and science.

Deng Xiaoping came to power in China in 1978 (unofficially, but we'll save that story for another time). At the time, China's per capita GDP was ~$200, ~35% of the population was illiterate, the country's education system had been devastated by Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, and the economy was a product of the period the Chinese call the "Century of Humiliation." Today, China's per capita GDP is ~$13,700, despite its 1.4 billion inhabitants. Mainland China doesn't participate in international education rankings, but Macau, Taiwan, and Hong Kong rank 2nd, 3rd, and 4th, behind only Singapore.

A small example and a gigantic one, both from countries that had a much worse starting point than Brazil's current situation. Therefore, it is perfectly possible to transform Brazil into a developed nation. In fact, we have the impression that the country has been improving in recent decades, albeit slowly. Accelerating this process would require greater contributions from our intellectual, economic, and political elites, who are the people best suited to lead significant movements. At this point, we will leave a provocation.

It's common to hear harsh criticism and dismissive comments about our own country. The vast majority believe they bear no responsibility for Brazil's plight. Many have plans to flee abroad if, in their eyes, Brazil doesn't improve. In a way, this is a democratic flaw. Each citizen is so small in the eyes of the State that they become alienated from public affairs and begin to see all evil as the fault of others. However, it's worth remembering the maxim "ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country." Collective transformations come from collective efforts. Each person contributes their seemingly insignificant effort, and the sum of all initiatives reaches enormous proportions. We need to replace the dream of moving abroad with the dream of improving Brazil.