The market makes mistakes

Dear investors,

After an optimistic end to 2023, with a strong rise in the IBOV index in November and December, the market returned to a general lackluster outlook for equity investments this year. Whenever prices fluctuate significantly, the natural reflex is to seek an explanation for what's happening in the economy that justifies the price movements and settle for the thesis that seems most plausible. However, this behavior implicitly carries the premise that the observed variation is an accurate reflection of reality, not a widespread mispricing.

There is some controversy surrounding the assumption that the market is always right. One group of economists and investors argues that prices are always the result of the best estimates available for each asset, reflecting the collective wisdom of active investors in the market who constantly evaluate the information available at a given time. Another group argues that investors occasionally make mistakes in their pricing or are forced to trade assets in the market for reasons other than intrinsic value analysis, resulting in asymmetries between the probable value of assets and the price at which they are being traded. Our view aligns with this second group and we believe that, today, the prices of some stocks on the Brazilian stock exchange do not reflect the fundamentals of their business.

Can the market really be wrong?

The longer we invest, the more skeptical we become of overly abstract arguments, in which there's no clarity about the concrete factors and agents behind a thesis. Thus, treating the market as an abstract, omniscient entity seems like a bad idea. One reason is that price doesn't exactly represent the collective opinion of all investors about how much an asset should be worth, but rather the equilibrium point between supply and demand for that asset at that precise moment. The concepts are correlated, but not identical.

There are several reasons that can prevent an investor from consistently acting on their convictions. The most common is simply a lack of available capital to act: if they believe an asset is too cheap but lack the liquidity to buy it, they won't participate in the day's price determination. If they need to consume capital for some reason (e.g., to cover operating losses), they may even be forced to sell assets they consider cheap. In times of economic stability, it's uncommon for several investors to find themselves in this type of situation simultaneously, but in times of crisis, this is expected to happen, and it becomes understandable that prices no longer are guided purely by intrinsic value analyses.

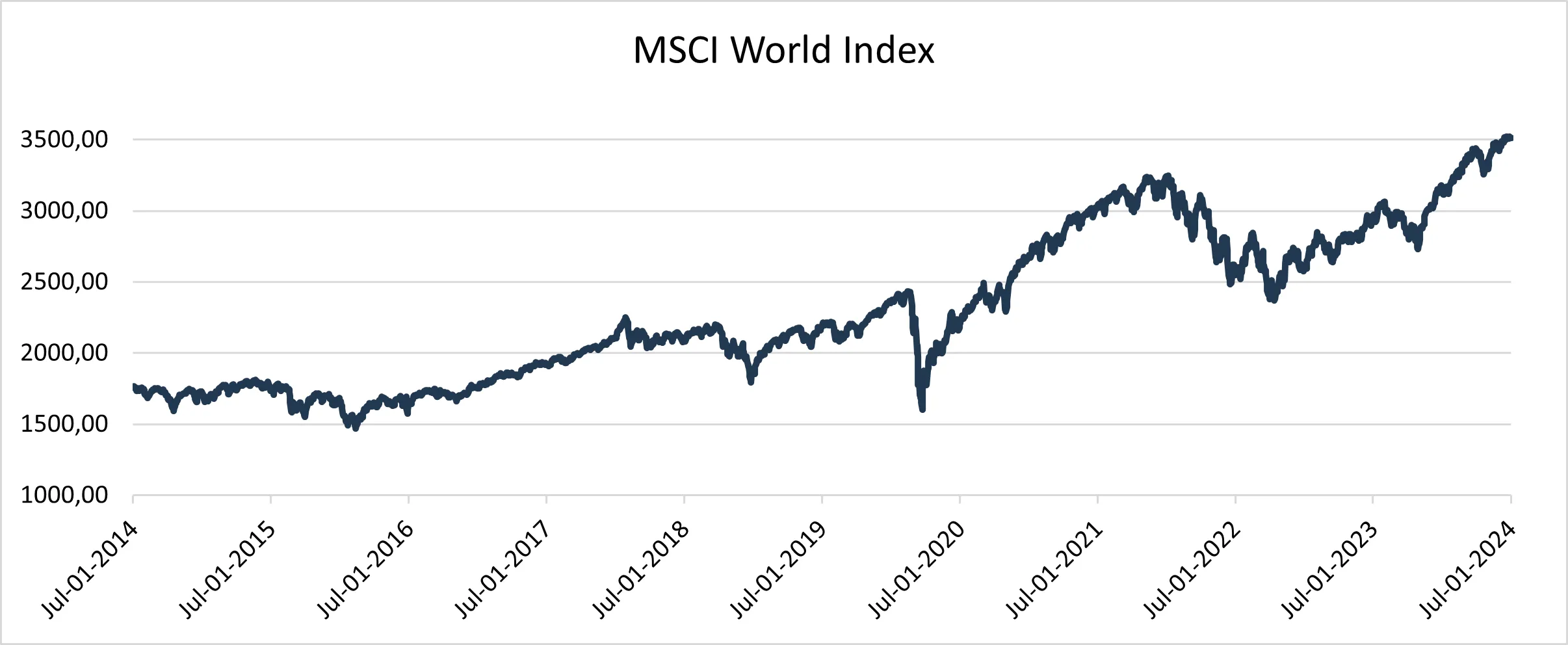

Another perspective that corroborates the fallibility of market pricing is observing how much stock prices fluctuate. The MSCI World Index is an index that considers the prices of approximately 1,500 companies from 23 developed countries, representing ~85% of the total value of these countries' stock markets. In other words, it is broad and diversified enough to be a good representation of the global economy. The fundamentals behind this index, almost by definition, cannot be very volatile, since the global economy is an enormously complex system and heavily dependent on productive capital (infrastructure, factories, machinery, etc.) and human capital (people's qualifications), two factors that rarely vary significantly over short periods. The types of events that could cause large fluctuations are technological revolutions, in the positive sense, and global catastrophes on the order of world wars, in the negative sense. However, this is the chart of the MSCI World Index over the last 10 years:

Not as stable as we might hope. Thus, in the absence of a series of events of global proportions that justify such observed volatility, it seems more reasonable to consider that market prices are not always adequate representations of the real economic value of the assets they represent.

Granted the possibility that the market may be wrong at times, let's analyze the current Brazilian scenario and consider whether we are in such a moment. There are two central topics of concern among many Brazilian professional investors today: the global inflationary crisis and the current government's pursuit of fiscal balance. Both topics are complex to analyze in detail, but we will provide a summary of current talk and our interpretation.

The impact of the global inflationary crisis on Brazil

The global inflationary crisis is nothing new. The BACEN (Brazilian Central Bank) began raising interest rates, the classic strategy to combat inflation, in March 2021. The Fed (Federal Reserve) began this move in March 2022, and the ECB (European Central Bank) in July 2022. The most recent development is that the Fed decided to keep interest rates high for longer than the market initially projected, similar to what we saw happen in Brazil. This has two main impacts.

The first is that, with higher US interest rates and concerns about the economy, many investors have decided to shift capital into US fixed-income securities, seen as the safest investment option. This migration has generated selling pressure in several other asset classes, including our small Brazilian stock exchange, where foreign investors currently represent approximately 55% of the total trading volume.

The second is that the Central Bank of Brazil (BACEN) has been hesitant to lower its base interest rate, despite inflation in Brazil over the last 12 months (June 23 to May 24) being 3.9%, considerably below the average inflation of 5.7% per year over the last 20 years. The argument presented by the Central Bank can be followed in the COPOM minutes, but it is well summarized in the excerpt "a scenario of greater global uncertainty suggests greater caution in the conduct of domestic monetary policy." There is considerable controversy surrounding the interest rate level maintained by the Central Bank. Since monetary policy is not our specialty, we will restrict ourselves to the observation that the current real interest rate is 6.6% per year, compared to the average of 5.1% per year over the last 20 years.

Our interpretation of these two factors is not positive, but it is milder than what we have heard from other investors. The selling pressure generated by the migration of capital to fixed income certainly affects stock prices, but it has no effect on the intrinsic value of the Brazilian companies whose shares are being sold and, therefore, is merely a temporary factor that does not change long-term return expectations. The extension of the contractionary policy by the Central Bank of Brazil (BACEN) hinders corporate growth and makes financing available to them more expensive while interest rates remain high, so there is an impact on the real value of businesses. However, the intrinsic value of each company is much more dependent on what the average long-term interest rate is expected to be than on the discussion of whether the Central Bank of Brazil will reduce interest rates a little further at the next COPOM meeting or in six months. In other words, the value deterioration caused by a few extra quarters of high interest rates is on the order of a few percentage points, not dozens of them.

The desired Brazilian fiscal balance

Since the beginning of Lula's administration, there has been tension surrounding the issue of fiscal balance, so the context is well known: the public sector currently spends more than it collects—the so-called fiscal deficit—and the government has resisted any spending cuts from the outset. Thus, the way to achieve fiscal balance is through increased revenue collection.

The government's thirst for revenue is also nothing new. We wrote in our October 2023 letter that we expected tensions surrounding fiscal responsibility to persist throughout Lula's administration, and we continue to hold that expectation, as the lack of fiscal austerity stems from the ideological conviction of leftist governments that the public sector should be expanded. This fact alone generates discomfort, as Brazil is not known for its low taxes, and pressuring the productive sector with even more taxes does not seem to be the best approach.

Furthermore, the way in which it has sought to increase revenue has created additional discomfort because, instead of admitting that taxes are being raised, the government has been arguing that it is merely correcting anomalies in the tax system by changing calculation rules and interpretations of tax benefits already granted. The practical result of these changes has always been to increase the effective tax rate, so there is clearly an increase in the tax burden, and the rhetoric that denies this fact understandably generates distrust among business owners and investors. Even more damaging is the uncertainty generated: what will be the next change, and which businesses will be affected? The range of Brazilian sectors that benefit from some type of tax benefit is enormous, and thus, much of the economy could be targeted by veiled tax increases.

On these points, we are aligned with the prevailing market view. We understand that this pursuit of revenue through unpredictable changes in tax rules is detrimental to the business environment in Brazil. However, it does not preclude investment. Our approach has been to assume pessimistic tax scenarios when estimating the fair value of each business. It is also worth considering that the impact of a tax increase does not necessarily directly reduce a business's profitability. Since companies in the same sector often enjoy the same tax benefits, a rule change impacts all competitors equally, and each company's competitive position tends to remain unchanged. The problem is that if the tax increase is fully passed on to prices, demand is expected to decline. Thus, the impacted sectors face the dilemma of forgoing growth or part of their profitability.

Is Brazil getting better or worse?

Anyone who invests in Brazil knows that periods are rare when there's no controversy or political upheaval on the horizon. Therefore, a good deal of instability and systemic problems in our economy are already incorporated into the price levels considered normal in our market. So much so that the average P/E multiple for the Brazilian stock market over the last 10 years is 10.3x, while the same multiple in the US market is 18.3x. Today, the P/E multiple for our stock market stands at 7.5x. So, the question is: is the current scenario really that bad?

A year ago, the IBOV index was very close to its current price. At the time, the SELIC rate was at 13.75% per year, with 12-month accumulated inflation of 3.2% (i.e., real interest rates of 10.5% per year), and there was still uncertainty about how long the Central Bank of Brazil would maintain interest rates at this level. GDP growth was expected to be 2.2% in 2023. Tax reform was still under discussion, with no clear prospect of approval, and the new spending cap rule was still pending, with a fiscal deficit already expected.

Since then, the SELIC rate has fallen 3.25% and real interest rates have fallen 3.9%. GDP grew 2.9% in 2023, 32% above the projected value. Inflation remains controlled, with a lower risk of a resurgence. Fiscal issues are still a problem, and are unlikely to disappear any time soon, but we are relatively better off than we were a year ago. Tax reform was approved, although the details of how it will be implemented are still pending, and we have a spending cap rule that, while far from ideal, limits public spending growth and tends to work as long as the economy continues to grow. In short, things have clearly improved in the last 12 months.

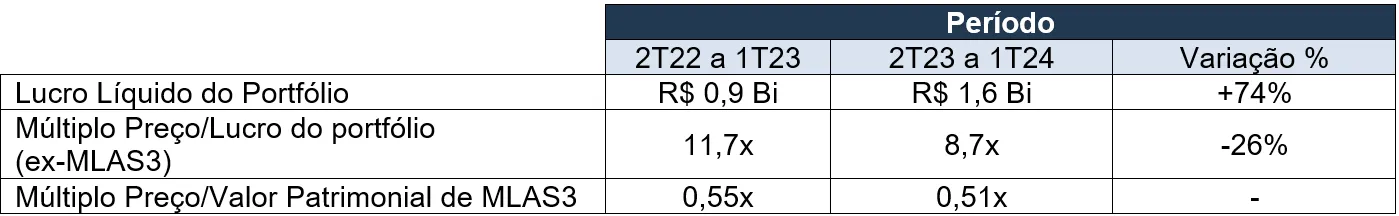

Even more important than these macroeconomic factors is the evolution of companies' results during this period. At this point, we will take the liberty of analyzing only what interests us: the profits and prices of the companies in which we invest through Ártica Long Term FIA. A comparison of the situation one year ago and today is summarized in the table below:

Note: Net Income and P/E multiple of the portfolio consider the individual indicators of each company weighted by the allocation of Ártica Long Term FIA in each company.

Due to this substantial improvement in the results of our invested companies, Ártica Long Term FIA has risen approximately 20% in the last 12 months. However, the Price/Earnings multiple of our current portfolio of Brazilian companies is lower than before. We segregated Multi (MLAS3) due to the negative net income for 2023, which makes the Price/Earnings multiple meaningless. The Price/Book Value multiple has remained stable even with the company's improved outlook today.

In other words, the fund is cheaper today than it was a year ago, in relative terms, even with a more favorable economic scenario and a clear trend of improvement in the operating results of the businesses in our portfolio. In our more thorough internal analysis, in which we estimate the fair value of each of the invested companies and compare it with their market values, we currently have an atypically high discount level. We see no justification for this price level as appropriate. It seems to us that these shares are simply cheap.

Still, there remains an argument we've heard quite frequently: there's no trigger expected to drive the stock market higher in the short term. However, when companies are doing well and their shares remain cheap, is it really necessary for any particular event to occur, or is it enough for investors to see the potential return implied by current prices and decide to buy again?