Impacts of population aging

Dear investors,

It's a natural tendency to pay more attention to things that suddenly impact the world. Technological revolutions, wars, and major political events dominate the news. Meanwhile, slow but persistent movements over decades generate silent revolutions. As in the fable of the race between the tortoise and the hare, consistency can take you further than speed.

We'll explore one of these silent revolutions. Two clear demographic trends have been observed in several countries: fewer and fewer children are being born, and people are living longer and longer. Within a few decades, we'll inevitably have more older people and fewer young people. This will have a profound impact on the economy, which will have to adapt to a different profile of the population available to work and consume.

We imagine this isn't news to anyone, but like everything that seems still very distant, it's rarely at the top of most people's list of concerns. However, change isn't far off. It's been happening for decades and will continue to advance day by day. Population aging is as fluid and certain as its own cause: the passage of time.

The decline in fertility around the world

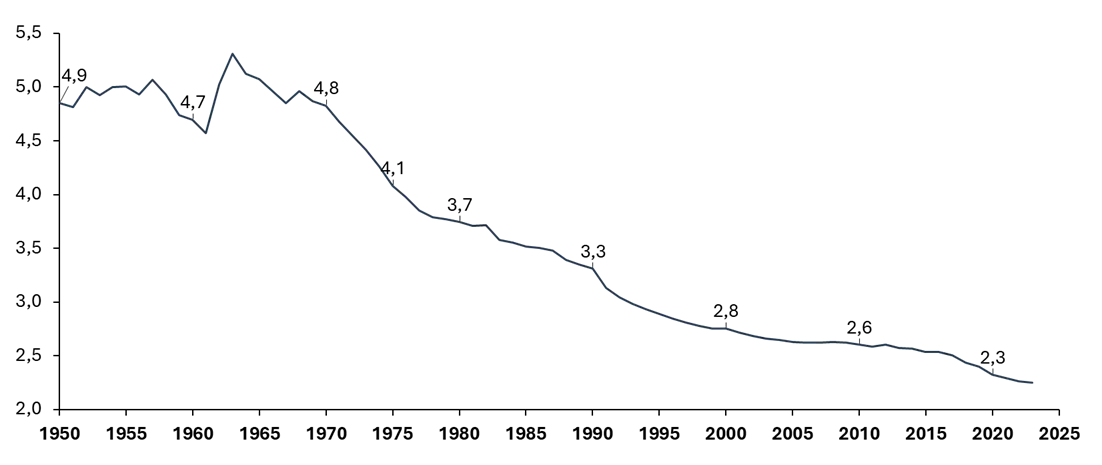

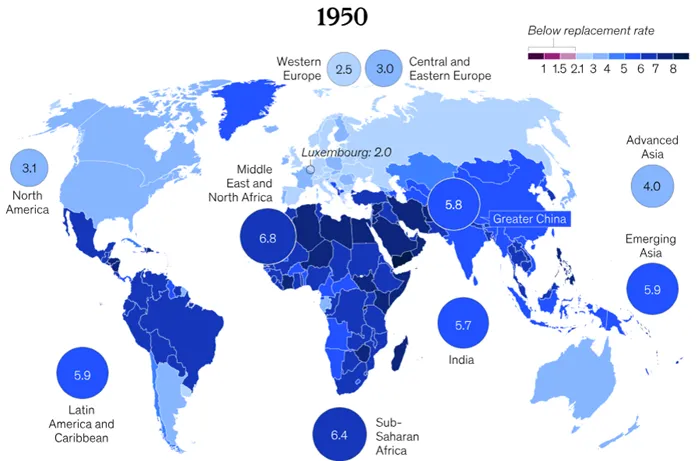

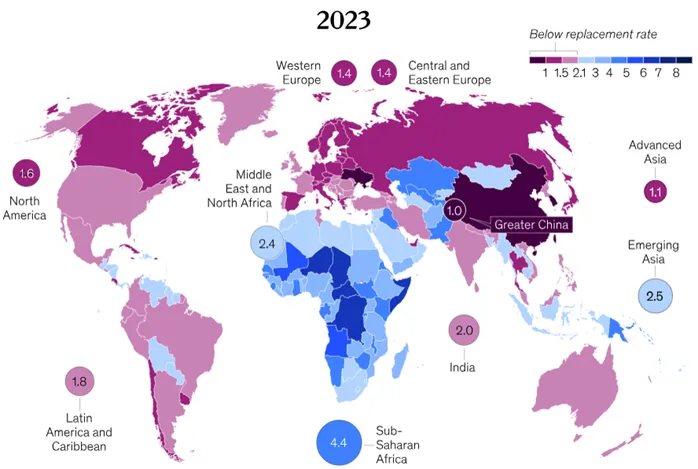

To maintain the population, women need to have, on average, 2.1 children over their lifetime. Today, the average global fertility rate is 2.3, slightly above the replacement rate, but with a highly uneven distribution. The underdeveloped world still has high fertility rates, while countries home to two-thirds of the world's population already have fertility rates below the replacement rate, including all developed economies on the planet.

The decline in fertility isn't a recent phenomenon, but it was quite abrupt from a historical perspective. In just over 60 years, global fertility fell by half. The graphs below put into perspective the magnitude of the change over the past few decades.

Global fertility rate (children per woman)

Source: UM WPP (2024), HFD (2024) –ourwordindata.org/fetility-rate

Fertility Rates Around the World – 1950 and 2023

Source: Mckinsey & Company – Dependency and depopulation: Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality

The changing demographic profile is a direct consequence of declining fertility. Increased life expectancy contributes to this, but approximately 80% of the phenomenon derives from the number of children born each year.

The demographic profile will advance in a very predictable way due to a truism: the number of people over 65 in the world in 2035 depends only on the number of people aged 55 alive today and the mortality rate, a stable statistical indicator. Thus, the fertility curve of recent decades determines the demographic profile of the coming decades in a completely irreversible way.

For future generations, the problem could be addressed by increasing the fertility rate. In theory, this would be feasible. Several countries with fertility rates below replacement have tried to encourage couples to have more children by offering financial support, tax benefits, and longer leave periods after each birth. However, no country has yet succeeded in restoring its fertility rate to the required 2.1. Therefore, the upcoming demographic shift is inevitable.

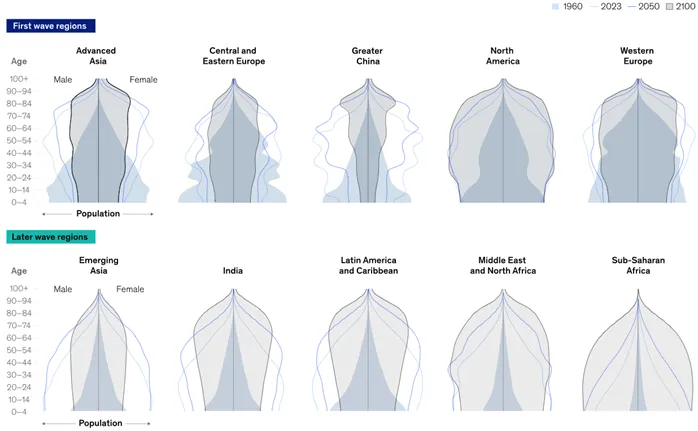

Changing demographics around the world

Source: Mckinsey & Company – Dependency and depopulation: Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality

Economic phases of life

To assess the impact of demographic changes on the economy, we need to make some simplifications. We'll outline the situations and behaviors with the greatest economic impact at each stage of a typical middle-class person's life to understand what will change as the number of people in each of these stages evolves over the years.

From birth until adulthood, people lack significant economic productivity and are dependent on their parents. They consume little, due to their more limited range of needs during childhood and their lack of autonomy in consumer decisions. The largest category of expenditure in raising children is education, at least in countries that do not offer quality public education. The remaining demands tend to revolve around basic living expenses.

From the onset of adulthood until around 35, the first phase of adulthood, the focus is on building a professional life and starting a family. This is a phase in which income tends to increase, but little is invested because expenses rise in parallel. In addition to expenses related to life's "infrastructure": housing, cars, and a variety of personal belongings, this is the first phase in which people begin to have more money and can decide for themselves how to spend it. With retirement still a long way off, it's more common to indulge consumer dreams than to invest for old age. After marriage and the birth of children, a new wave of costs related to childcare and education arrives. Couples continue to consume a good portion of their income while seeking career advancement and increasing their income, as this is a phase in which restraining consumption is difficult.

The next phase is full maturity, typically between 35 and 55. This is when one generally reaches the peak of one's professional life and one's income reaches its maximum level. Consumption increases accordingly, with a greater variety of destinations, as basic expenses no longer weigh as heavily. It is at this stage that discretionary consumption increases: travel, restaurants, and occasionally some luxury items. If children attend private universities, education may continue to be a significant expense. This also tends to be the time when spending peaks. Even so, it is the time when more significant investments begin to be made, when income levels allow.

From age 55 until retirement, usually around 65, is a phase in which income remains high and basic expenses tend to decrease. Careers are already well established, several assets have been purchased, and children are becoming independent. Some take advantage of the budget slack to increase personal spending and may indulge in some extravagances, but concerns about retirement become more evident and economic capacity develops, so this is the phase in which more investments are made.

Retirement is a significant milestone in economic life. Most people don't have full-pay retirement plans, so their salary drops or, at worst, stops completely. Consumption patterns tend to change significantly. Work-related expenses (transportation, clothing, eating out) cease, and healthcare costs increase. Some decide to simplify their lives, reduce recurring expenses, and dedicate more of their budget to other purposes. For example, they might move to a smaller home, adopt more frugal habits, and, at the same time, spend more on tourism or other leisure activities that were part of their retirement plans. Until about age 75, people are considered "young-elderly" and can remain quite active, so spending levels may not drop as much. On the other hand, investments tend to decline significantly, and the risk profile shifts to more conservative assets. The current phase is to consume what has been saved up to that point, taking care not to exhaust all the capital before the end of life.

From age 75 onward, consumption levels tend to decline. There's less desire for travel and many activities, so life tends to become more focused on family and domestic routines. This is the phase in which healthcare expenses increase, but the remaining budget returns to covering only basic living expenses. People start to think about what to leave to their children and may even make transfers while still alive. Investment profitability is no longer the focus, and the main concern is capital preservation.

With all the necessary caveats for a one-page summary of the entire life cycle, this schematic view allows us to reflect more clearly on the main changes caused by population aging.

Job market

Roughly speaking, a country's economic output depends on its active labor force, the number of hours worked per person, and its productivity level. A first indicator to consider is the percentage of the total population that actually works. Global standards consider the working age to be between 15 and 64, so the higher the percentage of the population in this age range, the greater a country's economic potential. The maximum percentage is around 70%, but population aging tends to reduce this indicator to somewhere between 50-60% in most countries.

The countries that experienced the decline in fertility rates first have already passed their peak working-age population. This group includes most European countries, the United States, China, and Japan, which is currently the most advanced in demographic changes and has been the case studied to predict the impacts of population aging. Most other countries, including Brazil, will reach their peak and begin their decline sometime in the next decade.

The first impact is the shortage of young labor, which primarily affects low-skilled labor-intensive activities. This phenomenon is already quite noticeable in several countries, and most of them have been resorting to immigration to fill the gaps that have emerged. One exception is Japan, which resists mass immigration and has suffered the most from the shortage.

The alternatives to immigration are difficult: increasing productivity or increasing the per capita workload. Increasing productivity has been pursued with some success through new technologies such as artificial intelligence, factory automation, and robotics. Increasing the per capita workload is a more difficult move. In theory, most countries have room for this, compared to the Chinese workload, but their populations are not receptive to the idea and vehemently resist any attempt to change in this direction. Immigration also has its problems, but we'll avoid that topic to stay focused.

If none of this is done, the consequence will be an economic recession. We don't see this as the end of the world, as quality of life depends much more on GDP per capita than on GDP growth itself. However, it would be a breach of dogma to accept that the economy will no longer grow, so efforts have been made to find a way to prevent this from happening. This is no trivial goal. Japan—a small, developed country with an atypical level of general discipline—has only managed to keep its economy more or less stagnant for three decades.

Even maintaining GDP per capita is not obvious due to the decline in the percentage of the working-age population. At the peak of 70%, there are 2.3 people of working age for every young person or retiree. In the 50% projected for some countries, there is only 1 person of working age for every dependent. It's a heavy burden to carry, and there is a limit to how much workload can be increased, so the world will rely heavily on productivity increases to prevent a decline in the average quality of life.

Social security problem

There is another, more complex and politically charged problem than the available workforce. Several countries, including Brazil, have structured public pension systems that have not effectively invested the contributions of the first generations of participants, trusting that contributions from future generations would be sufficient to finance the payments due to retirees. However, demographic trends will increase the number of retirees, public pension beneficiaries, for every active worker contributing to the pension. The direct consequence is that there are only two alternatives: contributions will increase or benefits will be reduced.

The government itself could, in theory, increase contributions, but most governments with pension problems also face fiscal problems. Therefore, they are more likely to raise taxes, increase contribution periods (postponing the retirement age), or adopt both measures, however unpopular they may be.

Reducing retirees' benefits is an even more sensitive issue, understandably. People plan according to the pension terms offered to them (or imposed by law) and make contributions throughout their lives. Reducing their benefits after retirement, when they are no longer able to work and have great difficulty reorganizing their lives, is a tremendous injustice. However, there is no painless alternative.

This discussion is likely to generate a potential conflict between generations, as the extra efforts fall on the younger population, which already expects to contribute more than it will receive when it's their turn to retire. Young workers are forced to adhere to a pension system that is clearly a bad deal for them, and implementing changes is not politically easy, as there will be an increasing number of voters in age groups who favor maintaining pension benefits.

Governments will likely resort to hybrid solutions that encompass all the alternatives: benefit reductions, tax increases, and longer contribution periods. The latter option seems the most palatable to us. One possibility would be to adopt a few extra years of work with reduced working hours, as life expectancy itself is increasing. But we have no intention of predicting each country's political decision.

The Brazilian case

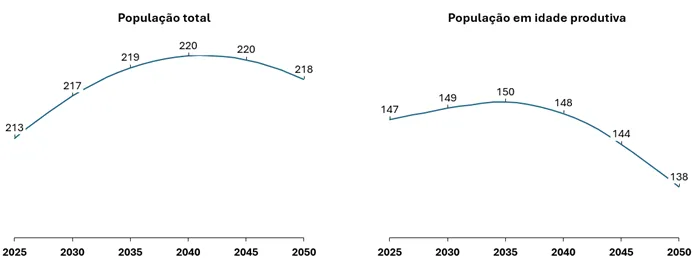

Brazil is in an intermediate demographic range. Our population continues to grow and is expected to peak around 2040, but the Brazilian fertility rate in 2023 was 1.6 children per woman, already below the replacement rate. The slow population growth that is still expected comes from increasing life expectancy. The working-age population will peak a little earlier, around 2035, but growth until then will be only 1.6%, with no significant demographic bonus from now on.

Projection of the Brazilian population (millions of people)

Source: IBGE, Arctic analysis

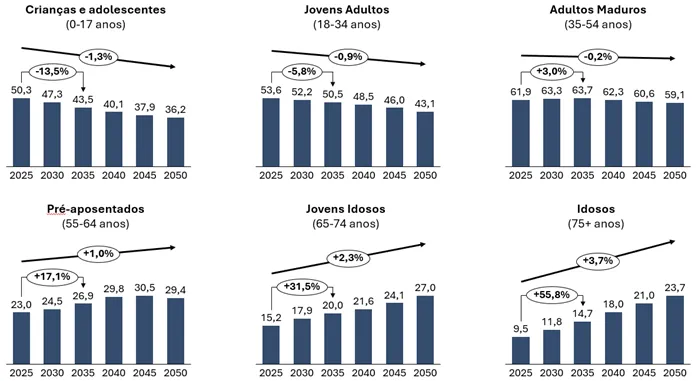

The most significant impacts for Brazil will come from the changing demographic profile. We adapted the IBGE projections to fit the age groups according to the life stages described above. This allows us to interpret the data in a qualitatively more relevant way to reflect on potential consumption and investment scenarios in the country.

Projection of the Brazilian population by age group (millions of people)

Impacts on the Brazilian economy

The most obvious impact of demographic change is on Brazil's consumer profile. Sectors targeting children, adolescents, and young adults are expected to face growth difficulties going forward. The most striking example is the education sector, particularly in the elementary and secondary education segments, as the number of children and adolescents will fall by 14% over the next 10 years. Other sectors affected include toys and games, clothing and accessories brands targeting adolescents, and youth entertainment such as nightclubs, festivals, and the like.

Sectors focused on the over-35 demographic will benefit, particularly in the older age groups. The senior population will grow by 41% over the next decade, equivalent to a constant compound annual growth rate of 3.5%. This represents a significant growth driver for the healthcare sector, for example. For reference, people over 65 spend about three times more on healthcare than those under 25. Tourism and leisure activities suitable for older people will also benefit from the increased number of retirees, with time and money at their disposal. Premium brands and luxury-related sectors are also likely to benefit, as age groups that typically have more budget space for this type of spending will expand.

For the same reason, the financial and wealth management industry is expected to grow, driven by the 17% increase in the number of people in the pre-retirement phase, when a larger portion of their income is invested, over the next decade. Mature adults, another target age group for the sector, will grow by only 3% over the period, but still contribute positively.

Services and products linked to productivity gains should accelerate their growth. The shortage of young workers will stimulate increased investment in this area, as it is expected to inflate wage levels and make automation and related technologies more economically advantageous, which may not pay off until labor prices rise.

There are sectors in grayer zones. The end of the population growth era should also imply a stagnation in urban infrastructure expansion, but this reasoning assumes that what exists today is sufficient. Brazil still has areas that would require significant investment to reach the recommended level for the current population, but this deficit is typically linked to the lack of economic capacity in these areas, so it's not obvious that expansions will occur. In Japan, where the population is declining, there are places where there are surplus houses. Real estate prices in these regions have been falling, and the construction industry has focused on renovating older buildings.

A less obvious impact is that the risk premium on investments in general tends to increase, as older investors will represent an increasingly larger share of total capital invested in the market, and risk aversion tends to increase with age. Another possible effect is that the benchmark interest rate tends to fall, due to the greater abundance of capital seeking low-risk fixed-income securities and the slower pace of economic growth, resulting from lower population growth, which reduces the demand for capital and, thus, interest rates. This has happened in Japan, and the European Central Bank makes the same prediction for the European Union (The macroeconomic and fiscal impact of population aging, 2022).

Impact on equity investments

For the stock market as a whole, the future is uncertain. On the one hand, falling interest rates would cause assets to appreciate. On the other, the increase in the risk premium would go in the opposite direction. Despite this uncertainty, this overall effect seems much less significant to us than sectoral effects like the ones we've illustrated. We believe that several good opportunities will arise for those who understand how population aging affects each business and have the patience to wait for the effects of this slow but deterministic change.

Currently, we have approximately 25% of our portfolio in investment theses that significantly benefit from population aging: Fleury e Blau, in the healthcare sector, and Banco Mercantil, which offers financial services specifically for the over-50 demographic. This percentage is expected to increase soon, as we recently approved an investment in a Japanese healthcare company. We plan to share more information about the deal once we reach our desired portfolio allocation.