Why have private pension?

Dear investors,

Historically, supporting oneself in old age was a private matter. People supported themselves with lifelong savings or relied on their children for support when they could no longer work. The first broad-coverage public pension system was created in Germany in 1889, during the reign of Otto von Bismarck, guaranteeing retirement benefits for workers over 70 (later reduced to 65 in 1916).

In the early 20th century, several countries followed Germany's example and created their own public pension programs. Brazil took its first step in 1923 with the Eloy Chaves Law, which created a fund called the Retirement and Pension Fund (CAP) for railway employees. This structure was soon replicated by several other professional categories, and the number of CAPs multiplied, each administered by a different employer and operating under the principle that resources accumulated through contributions could be used exclusively for benefit payments.

In the 1930s, under the Getúlio Vargas administration, CAPs (Retirement and Pension Institutes) belonging to companies within a single professional category were consolidated into Retirement and Pension Institutes (IAPs), and the government became part of the arrangement, participating in their administration and sometimes also contributing to the fund to subsidize certain professional categories. In 1966, the IAPs were unified into a single entity called the National Social Security Institute (INPS), a direct precursor to the current National Social Security Institute (INSS). When the government began to intervene in social security, already through the IAPs, the principle that pension fund resources could be used exclusively for benefit payments was abandoned. This was the seed of the pension problems that persist to this day.

Where does the pension deficit come from?

The logic of a pension fund should be quite simple. Workers invest monthly in the fund, the value of these contributions is invested over time, and the resulting assets are used to pay pensions. A reasonable rule is that the benefit is proportional to the years of contribution, except in exceptional cases resulting in death or premature disability. In a very large group of people, there will be those who receive more and those who receive less than the result of their own contributions, but since the factors that determine who will receive in each case are practically random, the homogenization of benefits is a simple mechanism for sharing and diluting life's risks.

A pension system created with these rules would have contributions much higher than benefits paid for many years, since those who retired soon after its creation contributed for a short time and will receive little, while those who joined the system at a young age will have decades of contributions ahead of them before receiving their pension. This wealth accumulation phase would only end when the youngest generation of contributors reached retirement age. If new contributors stopped joining the system, there would be no problem. The pension fund should have resources to pay until the last generation of retirees without relying on new contributions.

This wasn't the story of our pension system due to a public sector maxim: the government always finds a way to use the resources it has access to. The Vargas administration itself, which created the IAPs, interpreted the purpose of these institutions as defending the long-term interests of their beneficiaries, which went beyond paying pensions but also involved promoting economic and social development. As a result, pension funds began to be used to finance infrastructure projects and other politically beneficial investments.

The crucial question of how to finance the payment of beneficiaries' pensions was addressed based on the logic that pension funds would never run out, so contributions from future generations would be sufficient to support retirees' benefits, without the need to fully preserve the assets initially created. Simply put, the State decided it could appropriate the contributions made by parents throughout their lifetimes and use the contributions made by children to pay their parents' pensions.

There are a number of assumptions involved in determining how much money would need to be maintained in pension funds to be able to maintain retiree payments in this manner. For example, the population growth rate (how many children will support their parents' retirement) and the retirement age and average life expectancy (how many years parents will survive in retirement). Since adopting optimistic assumptions allowed the state to make more resources available for its own purposes, this was done.

The problem isn't unique to Brazil. Several countries, including several developed ones, have adopted the same principle that pension fund resources could be used for other purposes, and today they face pension deficits caused by two major secular trends: increasing life expectancy and declining average birth rates. In other words, fewer and fewer active workers are required to make contributions to fund the benefits of more and more retirees, knowing that when they themselves retire, they will most likely receive less than they contributed.

The most effective way to fix the problem would be for the government itself to cover the pension deficit and honor the terms in effect when contributions were made, but any issue involving the government becomes complex. The current government is not the same one that made the decision to appropriate pension funds, and there are no surplus funds to make the necessary compensation. It would be necessary to cut other public spending or increase taxes. There is no elegant solution.

The approach adopted by virtually all countries facing these problems was to reform their pension system rules. Brazil did so in 2019, with changes that increased the required contribution period and reduced the value of some benefits. This was a mitigating measure that did not solve the problem in the long term. The pension deficit still exists and continues to grow.

The solution is private pensions

As unfair as it may be to be forced to contribute to a social security system that carries a high risk of not paying its benefits in full in the future, there is no escape for most Brazilians. Contributions to the INSS (National Social Security Institute) are compulsory at source, deducted directly from the monthly payments made to those employed under the CLT (Consolidation of Labor Laws). The alternative is to save something beyond the mandatory contributions to build up assets that can be maintained under one's own control and guarantee sufficient resources for a comfortable retirement.

Recognizing the inadequacy of the public pension system, the Brazilian government created the Supplementary Pension Scheme (RPC) in 2001, an optional membership system that grants certain tax benefits to those who create private pension plans. The available options are the well-known PGBL and VGBL, both with the option to choose between progressive or regressive taxation. Details on each type of plan are available in various places, so we will focus only on the most important features of the PGBL and VGBL and the regressive taxation system, which will be the most advantageous for the vast majority of our investors.

PGBL

The benefit of the PGBL is that you can invest up to 12% of your annual taxable income in pension funds, and this amount will be exempt from the income tax (IR) that would otherwise be levied that year. On the other hand, the entire balance invested in these funds will be subject to income tax upon withdrawal. There are two significant advantages to this arrangement.

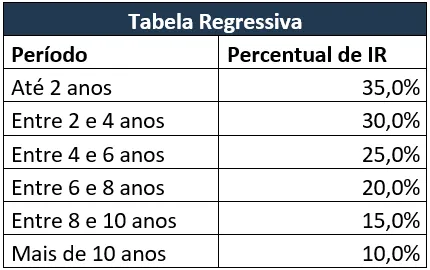

The first is that the IR rate can be reduced from 27.5% to up to 10.0%, under the regressive taxation regime, as the rate falls over the period of permanence in the pension plan, as per the table below:

From the fourth year of investment onwards, the rate is already advantageous and, considering that the intention is to save for retirement, it is not difficult to reach the 10 years necessary to take advantage of the maximum reduction.

The second advantage is that, even if the income tax rate were the same, not paying the tax now but only paying it when withdrawing the investment (deferred income tax) yields a significant difference in return over long periods. In 20 years, the investment with deferred income tax would be worth approximately ~17% more than an investment with the same return but with annual income tax payments. This is the same benefit that exists for investments in equity funds.

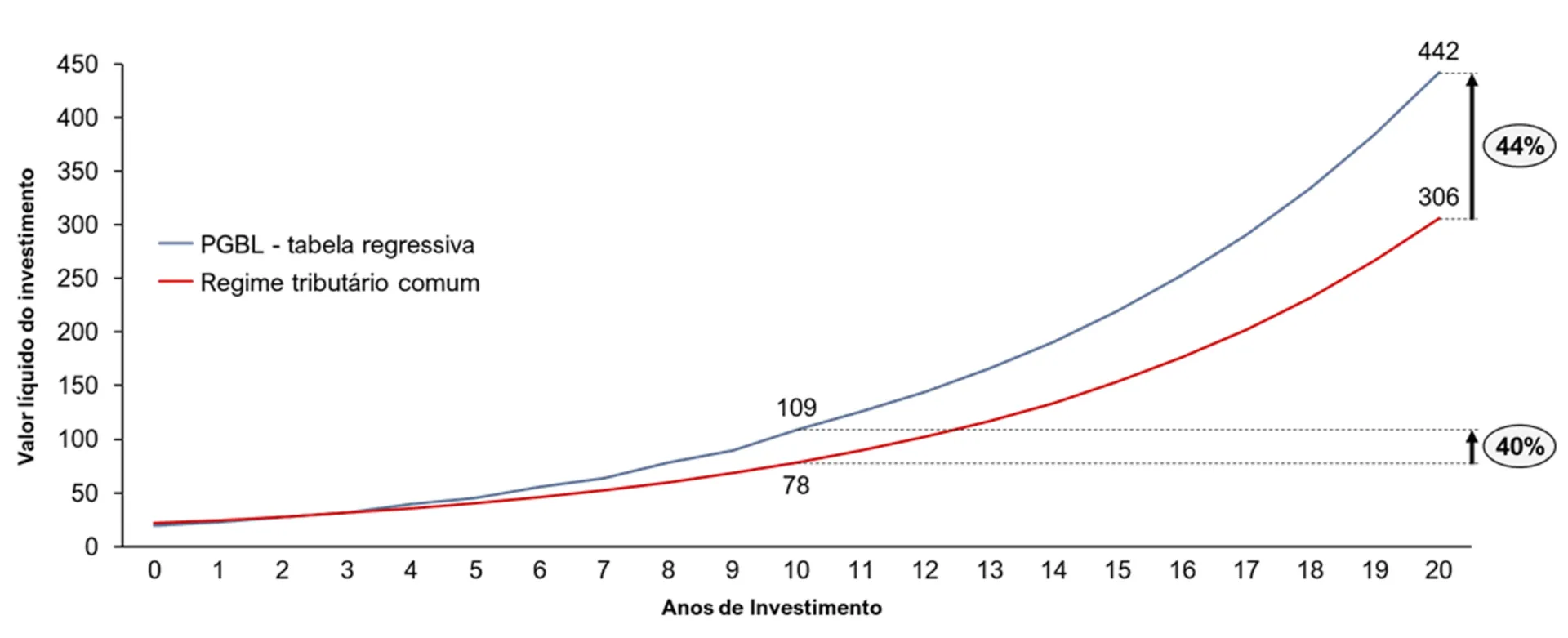

Combining the tax rate reduction and the income tax deferral, the difference is enormous. We simulated the case of someone earning R$250,000/year and investing R$30,000 (R$121,000 of their annual salary) in a pension fund with an annual return of R$151,000. If the investment is redeemed after 20 years, its net value will be R$441,000 higher than the value of an equal investment without the PGBL tax benefit.

Investment simulation in PGBL with regressive table

In short, for those who work under the CLT (Consolidation of Labor Laws) and earn in the upper income tax bracket, it is quite advantageous to invest in a PGBL (Property-Based Loan Plan) with a regressive tax regime. If possible, invest up to 12% of annual salary and for a period longer than 10 years.

VGBL

The VGBL's tax benefit is simply a reduction in the tax rate under the regressive tax regime, from 15% applicable to capital gains to 10% starting in the 10th year of investment. However, the VGBL has a useful feature for estate planning: in the event of the holder's death, the invested amount can be transferred to a designated beneficiary without going through the probate process and without charging ITCMD (from 2% to 8% of the estate, depending on the state of residence), as the VGBL operates similarly to life insurance.

There are two typical use cases for this VGBL mechanism: the first is when the probate process is expected to be lengthy and some heirs are unable to support themselves independently. The VGBL is a way to quickly transfer a portion of the estate to these heirs. The second case is when there is a desire to divide the inheritance differently than provided by law, since the VGBL is not included in the estate to be divided among the heirs. In fact, anyone can be named as a beneficiary of a VGBL plan, whether they are an heir or not.

What is the best strategy for investing in retirement?

As the Chinese saying goes, "The best time to plan a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now." The sooner you start saving for retirement, the smaller the amount you need to invest, as the effect of compound interest increases exponentially over time. So, anyone who doesn't yet have a retirement investment strategy should start thinking about one as soon as possible.

There are two basic principles that stem from the nature of these investments: you should invest with the very long term in mind, and there's no need for liquidity, as the idea is to only withdraw these funds upon retirement. Thus, the goal is to seek the best possible rate of return over decades, while maintaining a healthy dose of prudence. Price volatility unrelated to the fundamentals of the invested assets matters little, as, over very long periods, these market fluctuations tend to cancel each other out, and the return converges to how much the fundamentals have actually evolved. This mindset makes sense whenever there's no need to use the invested resources in the short term. The good principles for building wealth are the same regardless of the ultimate purpose of using the accumulated capital.

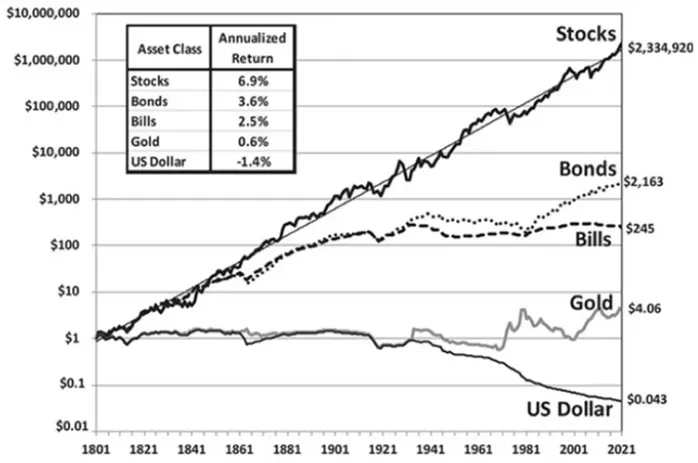

This is the investment philosophy we adopt in our funds, and we choose to invest in stocks because it is the asset class with the highest returns over long periods, a point well illustrated by Jeremy Siegel, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania (Wharton School), who collected investment data in the United States over 220 years and compiled it in the graph below.

Comparison of returns between stocks, fixed income, gold and the dollar

Source: Stocks for the long run, 6th edition (Jeremy J. Siegel)

Some argue that this conclusion doesn't apply to Brazil, since the IBOV has had returns very similar to those of the CDI in recent decades, with much greater volatility. However, our market offers many opportunities for those willing to select the best companies on the stock exchange and invest in them during times of stress, when prices fall sharply. We've been doing this for over 11 years, and the average return we've achieved since Ártica Long Term FIA was founded to date has been 29.2% per year, equivalent to 314% of the CDI return over the same period.

Launch of Ártica Previdência

Although our philosophy is well-suited to retirement investments, it wasn't previously possible to invest with us through PGBL or VGBL, as these plans require investments to be made only in funds created specifically to receive retirement funds. However, we have something new.

We just launched Ártica Previdência FIM, which went live last Friday (November 29th). We will follow the same investment strategy as our other funds (Ártica Long Term FIA and Ártica Polaris FIA), with two changes: first, pension funds cannot have more than 15% of their portfolio invested in a single stock, so Ártica Previdência will be slightly more diversified; second, the new fund will no longer need to maintain at least 67% of its capital invested in stocks, a requirement that equity funds be exempt from the come-cotas tax. This means we will have flexibility to invest, in addition to Brazil's most advantageous tax regime: an income tax rate on capital gains of up to 10% without come-cotas.

Ártica Previdência FIM is now available to BTG clients, along with Ártica Long Term and Ártica Polaris. Our funds are not publicly available on the product platform, so the first contribution must be made by requesting it from your BTG account advisor. After the first investment, the funds will appear in the bank's app, and additional contributions can be made independently. If you have any questions, we are available to help on WhatsApp. (11) 97891-7619.