Why invest in stocks outside Brazil?

Dear investors,

Our investment history is almost entirely in the Brazilian stock market. While a large portion of Brazilian investors believe that our stock market is not a good investment environment, due to the country's political and economic turmoil and the famous comparison of the IBOV's return with the CDI's over recent decades, we have a different view. Although a passive equity investment strategy doesn't have very attractive prospects, there's plenty of room for good returns with active management. This is the strategy we've successfully executed over the past decade. However, we've recently begun to look outside Brazil.

In 2022, this international investment theme gained some prominence, as several multimarket funds invested in foreign economies, and even the general public began seeking investments abroad, through new brokerages offering accounts for trading abroad. However, this movement was driven by concerns about the Brazilian economy and the consequent desire to diversify into other geographies, while our motivation is quite different. Let's explain why we still like the Brazilian stock market and why, even so, it made sense for us to seek investments in other countries as well.

The good side of the Brazilian stock market

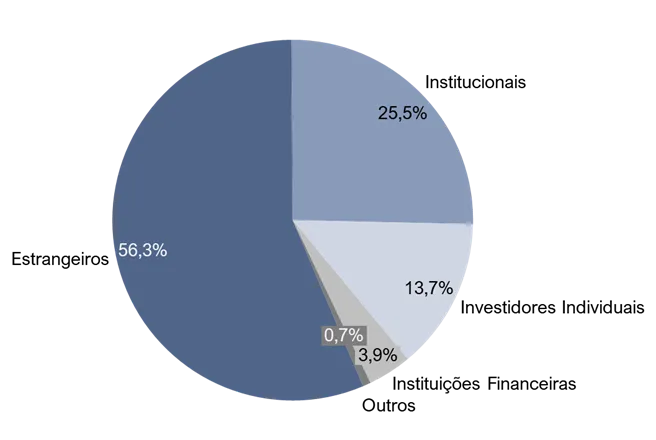

Investing in stocks is a competitive activity. To achieve above-index returns, it's necessary to be more accurate than the market average. As in any competitive dynamic, the first thing a participant wants to know is who the other competitors are and how challenging it is to overcome them. Therefore, an important question is: who invests in the Brazilian stock market? A good reference for this information is the share of each type of investor in the total volume traded in the spot stock market, as reported monthly by B3 itself:

Investors in B3's Total Monthly Volume (April 2024)

For foreign investors, Brazil is a completely peripheral market. The total value of companies listed on the Brazilian stock exchange represents ~2% of the global stock market, and only ~70 companies are worth more than ~2 billion. Below this value, the American market classifies stocks as small caps. In other words, for an American institutional investor, we are a small emerging market of small caps. Many foreign investors who invest in Brazil do so as part of a portfolio diversification strategy in emerging markets, evaluating the average valuation of the stock exchange and the expected growth of the Brazilian economy relative to that of developed economies. Few will conduct in-depth analyses of Brazilian companies.

Individual investors have diverse profiles, but they generally lack in-depth technical knowledge and lack the free time to dedicate to stock analysis. Most perform superficial analyses or follow the recommendations of a subscription service that provides market analysis.

That leaves institutional investors and financial institutions. These are professional, qualified investors with dedicated teams and information systems. However, this category encompasses both equity funds and other types of funds, particularly multimarket funds, and many of them do not have active equity management strategies. They may follow the index portfolio and tactical variations around it, or pay more attention to balancing stocks with other asset classes than selecting the best stocks.

In other words, fewer than 30% of Brazilian stock market participants (potentially, far fewer) are actively conducting in-depth analysis of specific companies. Furthermore, many investment funds still face the problem of having a volatile investor base, which becomes desperate when market sentiment deteriorates and begins to withdraw. Therefore, even if the fund manager believes it's time to buy more, they may be forced to sell to return the money to their shareholders.

This is the competition we face in Brazil. The typical investor operating on our stock exchange pays less attention to the details of listed companies than to the country's macro environment. This generates stock price volatility that is sometimes uncorrelated with each company's expected financial results. This is the perfect environment for fundamentalist investors to operate: a market where stock prices fluctuate significantly around each company's estimated intrinsic value, which is precisely the prerequisite for opportunities to buy low and sell high.

The bad side of the Brazilian stock market

On the other hand, there are three characteristics we consider detrimental to our stock market. The first is the small number of assets. Today, there are 340 companies listed on the B3, and only 214 of them have liquidity greater than R$500,000 per day. This is still considered quite low, but it allows us to operate with small positions. This significantly limits the range of opportunities we have to evaluate.

The second negative factor is that the Brazilian economy lacks strength in sectors that simultaneously offer high profitability and global competitive advantages. For example, several of our listed companies operate in commodities sectors, characterized by volatile results that make it difficult to accurately estimate their fair value. Others are highly regulated or state-controlled, with the resulting unpredictability brought on by potential political interference. Removing businesses in sectors we deem uninteresting from the list leaves between 100 and 150 companies. This is a fairly small pool of opportunities, and consequently, the number of excellent investment theses available in this sector is quite limited.

The third aspect is Brazil's legal uncertainty, particularly regarding tax matters. In many businesses, even with diligent and responsible executives, significant legal disputes arise over the amount of taxes owed by the company. The inconvenience of this scenario for investors is that, in many investment cases, there is a chance that the company could lose a significant portion of its value if the court ruling goes against its request. Litigation is often complex, with highly uncertain conclusion times and outcomes. To illustrate how disruptive this is, in one investment case, we evaluated a tax dispute that had been ongoing for over 10 years. We read over 500 pages of legal proceedings and met with several lawyers. The result of all this work was an estimate of the magnitude of the losses associated with each possible outcome scenario, a very vague notion of the chances of each scenario materializing, and the expectation that the case would still take years and years to resolve.

Why we started looking outside

The balance of the positive and negative aspects of the Brazilian stock market still seems positive to us. It offers good investment opportunities, with some frequency, for those willing to carefully select the companies in which to invest. However, international stock markets caught our attention because an atypical window of opportunity emerged.

What developed countries are now facing are inflationary crises very similar to Brazil's, the difference being that Brazil began combating inflation about a year before the United States and Europe. Thus, while our central bank is already cutting interest rates, central banks in other countries are still at a similar stage to Brazil's in the second half of 2023: at the peak of interest rates, discussing how long they will have to keep them at that rate or whether any further increases will be necessary.

Investors' reaction to this rising interest rate scenario around the world was the same as what we saw in Brazil: there was a large migration of capital from equities to fixed-income securities, and consequently, stock prices fell due to the pressure of selling. As a result, several stock exchanges are at valuations well below their historical average, the same scenario we see here in Brazil. The current supply of cheap stocks is a global phenomenon.

Amid this tumultuous macroeconomic environment, it's worth noting that not everything is cheap. Amid attractive average valuations, there are bargains and companies trading at bold prices. A notable example is the price level of American big tech companies. These are undoubtedly excellent companies with great potential, but it's not obvious that valuations in the range of 25 to 60 times price/earnings are great bargains.

Is investing abroad more difficult?

The major disadvantage of investing abroad is having to deal with the risk of exchange rate fluctuations, which are like commodity prices: impossible to predict. In theory, the exchange rate between two currencies should vary only based on the difference in inflation in both currencies, but in practice, the real exchange rate can remain far from this theoretical equilibrium point for very long periods. For example, the analysis below shows the exchange rate between dollars and reais (USD/BRL) since 1999, when Brazil adopted a floating exchange rate regime. The red line is what the exchange rate should have been over time if the theory worked perfectly, and the blue line is the real exchange rate.

Real vs. Theoretical Exchange Rate (USD/BRL)

The analysis serves as a benchmark for where the exchange rate should gravitate in the long term, but it doesn't help much in predicting what the exchange rate will be in the coming years. The problem with this is that a large exchange rate fluctuation can ruin the return on a successful investment from the perspective of the invested company's local currency, if the capital is converted back into reais at a much worse rate than the one prevailing at the time the investment was made.

We take two precautions to mitigate exchange rate risk: the first is the good old-fashioned margin of safety: to invest outside Brazil, we require a larger discount on the share price in relation to its fair value, to compensate for the extra risk; the second is to avoid investments in cyclical businesses abroad, as the exchange rate could be unfavorable at the time of the sector cycle when it is appropriate to sell the shares.

Aside from exchange rate issues, there are no major impediments to investing in other countries, as long as we select those with stable economies and business environments we understand. The type of fundamental analysis we perform is applicable to any geography, and today, physical location matters little when it comes to gathering data and communicating. Scheduling video conferences with executives in London is as simple as scheduling with executives in São Paulo.

The advantages of looking at the whole world

The main impact of looking outside Brazil is that we've expanded our universe of potential investments from 214 companies to over 25,000 listed stocks worldwide. The advantage is statistical: the chance of finding extraordinary opportunities in a sample size of 25,000 stocks is much greater than finding something extraordinary among 200 local stocks, just as it's easier to find a 2.20-meter-tall person in a group of 25,000 people than in a group of 200. Thus, we can be much more rigorous in our selection criteria and still expect to find stocks that meet our requirements.

Another advantage is that the stock markets of developed countries are much larger than Brazil's, both in terms of company size and the size of the investment funds operating there. In the American market, equity funds with less than USD 1 billion are considered small, and those below USD 10 billion are still considered medium. This is why companies valued under USD 2 billion are considered small caps.

Today, Ártica Long Term has approximately R$ 250 million (~USD 50 million) under management, a tiny size by global standards, which translates into a relative advantage for operating in developed markets. For us, it's a good investment of time to deeply analyze a company where we can allocate R10% of our portfolio (USD 5 million), with daily liquidity above USD 100,000. For a typical American fund, stocks of this size are too small and not even worth the effort of analyzing. In other words, we won't be competing with the good American managers when evaluating shares of companies valued at USD 1 or 2 billion. Since what matters most to us is the return generated for our investors, we will continue to make the most of the advantage afforded by our current size and seek to operate in the least competitive environments possible.

What we have done so far

For about six months, we've been looking at stocks in places with business cultures we're already somewhat familiar with: the United States and Western European countries. So far, we've invested in two companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. The fact that they're both British is a coincidence; we didn't find them specifically targeting England.

One of them is a small-cap that fits well into the typology we described, with a market cap of ~R$ 600 million and daily liquidity of ~R$ 750,000. It's too small for most UK funds to appreciate. It grew by an average of 21% per year over the past 5 years and maintained an average return on equity of 15% per year in pounds sterling. We bought shares in this company at a valuation of approximately 5x Price/Earnings.

The other is a large-cap company worth tens of billions of dollars. It's a mature global company that no longer experiences significant growth, but maintains good profitability, strong cash generation, and is trading at 7.5x Price/Earnings, while it used to trade between 10-15x Price/Earnings before the inflationary crisis. In this thesis, what attracted us wasn't exactly these price references, but the fact that the chance of losses is low and there is potential for significant appreciation of the business within a few years, due to changes in the sector context.

As you've noticed, we don't want to disclose the specific companies yet, as they are small positions in our portfolio, and we may still buy more. If they reach a significant size, we'll provide more details in a future letter.