Dear investors,

The European Central Bank decided to start cutting its base interest rate in June this year. The Federal Reserve followed suit and cut US interest rates in September. Meanwhile, the Central Bank of Brazil (BACEN) had already been cutting the SELIC rate since August 2023. The early move was consistent because Brazil began its monetary tightening cycle much earlier than developed economies, probably due to its greater experience in dealing with inflation problems. However, a surprise came last month.

Contrary to the trend of the most important central banks in the global economy, the Central Bank of Brazil decided to reverse the direction of interest rates and approved a small increase, from 10.5% to 10.75%. Today, the market estimates that we will return to 12.5% and some say that we will reach 13.75% again. A few months ago, no one was talking about this possibility. We can learn two lessons from this recent history.

The first is that macroeconomic projections are very unreliable and do not serve as a good basis for investment theses. We already wrote about this in February 2022, in the letter “How to deal with the macroeconomic scenario”, but nothing like a fresh example to reinforce the point. The second is that there is wisdom in the culture of traditional Brazilian entrepreneurs, who prefer to keep the level of debt of their companies lower than what financial theory says would be ideal. Practically all of the business literature that predominates in Brazil is imported from the United States and most of it is directly applicable. However, some points need to be tropicalized. The way of dealing with corporate debt is one of them.

Why almost every company has debts

A company has two main sources of capital external to the business itself: equity, invested by its shareholders, and debt, granted by creditors. The basic function of a company is to remunerate this capital invested in its operations at a satisfactory rate, which is called the cost of capital.

A company's ability to generate operating results is independent of the source of the resources invested in its business. The agreement between shareholders and creditors determines only the division of profits. Shareholders want to obtain the highest possible return, accepting a certain level of risk, while creditors want the return predetermined in the debt contracts, running the lowest possible risk of not receiving it. Thus, the agreement is that creditors have priority in receiving their share of the profits and, in return, accept a predetermined return lower than the profitability that shareholders expect for the business.

If the return on the company is, in fact, greater than the cost of debt, the shareholders will keep the surplus and the return on equity will be greater than the return on the business itself. For example, if a company has 50% of its capital in the form of debt and 50% in equity, the cost of debt is 14% per year and the return on the business is 18% per year, the return on equity will be 22% per year (0.5*14%+0.5*22%=18%). If the return on the business were 10% per year, the return on equity would be 6%. This is the concept of leveraged return. The greater the share of debt in a company's total capital, the more leveraged the return on equity, for better or for worse.

An important detail is that the cost of debt is not constant. The more debt a company takes on, the greater the risk that creditors will not receive the agreed return, since a larger portion of the profits is needed to cover interest and debt repayments, and any variation in the profitability of the business may cause the generation of operating cash to become insufficient. Therefore, the cost of debt increases in line with the increase in the share of debt in the capital structure.

The theory goes that the ideal scenario is for a company to finance itself with debt up to the point where the cost of taking on additional debt equals the cost of equity capital. This would be the optimal leverage point, which would generate the best leveraged return on shareholders’ capital. We will debate whether this point is truly optimal, but it is fair to conclude that it will almost always make sense to have debt, since the cost of debt is usually substantially lower than the cost of equity capital while debt is low.

The Brazilian reality

Theoretical calculations often fail to be accurate in real situations. Even engineers apply safety factors to their calculations to reduce the risk of reaching the theoretical limit. The same practice applies to business management, which deals with much more uncertain situations. This is especially true for businesses in Brazil.

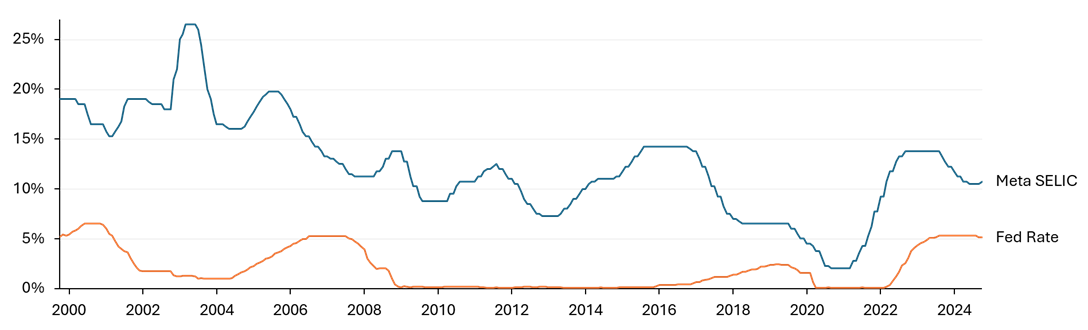

In the US market, it is a little easier to deal with the issue of leverage. The economy is more stable and the standard is for corporate debt to have pre-fixed interest rates. There is still uncertainty about business results, but the cash flow needed to cover interest and amortization is known from the outset. In Brazil, it is more common for corporate debt to be post-fixed, indexed to the CDI, and we know very well how much our economy fluctuates. The graph below compares the evolution of the SELIC, the base interest rate in Brazil, with the Fed Rate, the base rate of the US economy.

SELIC Target and Fed Rate History

Source: Central Bank of Brazil and Federal Reserve

The difference in stability and the range of variation between the two rates is notable. Brazilian interest rates fluctuate so much that creditors themselves prefer not to take the risk of carrying out pre-fixed operations, or they demand such a high return premium to cover this uncertainty that most businesspeople prefer to take on post-fixed debts and face the problem of having a fluctuating financial cost over the years.

In addition to the unpredictability of financial expenses, there is an aggravating factor for companies. When interest rates rise, the economy as a whole slows down. It becomes more difficult to increase revenue or pass on prices, and business results tend to be weaker precisely when more cash flow is needed to cover debt interest. Many companies end up unable to honor debt payments and default. With a higher level of default, creditors demand an even higher risk premium and the problem deepens.

The average cost of corporate credit in Brazil (excluding subsidized lines) is around CDI + 10%. With the current SELIC rate, this means that companies would need a return above 20% per year for it to make sense to take on debt. Very few businesses consistently achieve this level of return. Debts with a reasonable cost end up being only those with real guarantees or endorsements from highly capitalized partners, or raised by very large companies that are well-known in the financial market. For the rest, the cost of debt in Brazil is prohibitive and most credit operations end up being made at times when the entrepreneur has no other option, and not because it is really worthwhile.

The common sense of traditional Brazilian businesspeople, that it is better to simply avoid debt, is a sound recommendation in this environment where we have an unstable economy, volatile interest rates and such a high bank spread.

Why is Brazil like this?

Most business owners blame the banks. Seeing interest rates rise precisely when the company is going through a difficult phase, they say that the banks' credit logic is to rent an umbrella when it's sunny and ask for it back when it starts to rain. In turn, the banks say that the blame lies with the business owners, who plan poorly, manage their businesses poorly and generate a level of default that requires high interest rates for the credit operation to remain viable. The tendency to point the finger at the immediate counterparty is understandable, but the problem comes from a broader context.

The bank operates in the manner necessary for its own business to be profitable. The entrepreneur takes on debt when he believes he will get a sufficient return or when there are no alternatives to keep his business alive. The problem is that making accurate financial planning in an economy that has had its base interest rate varying between 2 and 14% in the last 5 years is like building a house of cards on a rocking chair.

The necessary solution is for the economy to be managed in a more stable manner, with a government that adopts more conservative fiscal practices and a central bank that values market stability. However, we are aware that this statement is like the insight of the young manager who concludes that the solution for a company in difficulty is simple: increase its revenues and reduce its costs. We do not have high expectations that the Brazilian economy will improve any time soon, and pragmatism leads us to simply accept that this is the scenario we have to deal with.

How to invest in this environment

Due to high interest rates and economic uncertainty in Brazil, many people conclude that it is best to invest in credit securities. However, both debt and equity are subject to the same business risks related to the invested company. The difference is that equity serves as a buffer against possible losses imposed on creditors. This protection works well when the fluctuations in results are small, but it is not effective in extreme cases, in which the company files for bankruptcy protection and requires creditors to write off part of the value of the debts to enable the recovery of the business (again, see the case of Americanas). It is like having a seatbelt, which reduces the risk of damage in any collision, but is much more effective in a car accident than in a plane crash.

Since fixed income is very popular in Brazil, it is common to see credit securities with lower return premiums than we believe would be appropriate for the related risk. Pricing sometimes seems to ignore the chance of more serious problems, which would affect both shareholders and creditors. Thus, our preference is to invest in stocks, with direct exposure to business risks, but without the contractual limitation of return that fixed income securities have.

Knowing this exposure to risk and the fact that we live in a volatile economy, investing in businesses that would yield excellent returns in a stable scenario can be a trap. Even when everything seems to be going well in Brazil, which is clearly not the case today, it is unlikely that we will go many years without a new crisis. Therefore, we seek to invest in businesses that are capable of weathering varied macroeconomic scenarios without collapsing. Generally, this means not investing in highly leveraged companies.

There was a time when several American business schools argued that companies should pursue their optimal capital structure, which usually resulted in high leverage. It was even argued that indebted companies were better managed, since executives would be required to maintain the cash flow discipline required to meet interest and amortization payments. A famous analogy compared this logic to the claim that drivers would drive more cautiously if there was a knife stuck in the steering wheel and pointed at their chest.

Warren Buffet criticized this line of thinking, saying that no one in their right mind would put a knife in the steering wheel to drive better, because even if this reduces the risk of accidents, any small collision can still pose a risk of death. The same goes for companies. Situations that a non-leveraged business would go through without major problems could lead to bankruptcy for a heavily indebted one.

We believe that the more uncertain the economic scenario, the more important it is to prioritize the resilience of results, rather than seeking theoretical optimums. Leveraging too much in Brazil is like putting the knife in the steering wheel and driving on a bumpy dirt road. Not very wise.

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.