Dear investors,

After an optimistic end to 2023, with a strong rise in the IBOV in November and December, the market returned to general discouragement with variable income investments this year. Whenever prices fluctuate a lot, the natural reflex is to look for an explanation about what is happening in the economy that justifies the price movements and settle for the thesis that seems more plausible. However, this behavior implicitly carries the premise that the observed variation is an appropriate reflection of reality, and not a generalized pricing error.

There is some controversy about assuming that the market is always right. A group of economists and investors argue that prices are always the results of the best estimates that can be made regarding each asset, a reflection of the collective wisdom of the group of active investors in the market who constantly evaluate the information available at a given moment. Another view says that the investing public occasionally makes mistakes in their pricing or is forced to trade assets in the market for reasons other than intrinsic value analysis, so that asymmetries arise between the likely value of the assets and the price at which they are being traded. Our vision is aligned with this second group and we believe that, today, the prices of some shares on the Brazilian stock exchange do not reflect the fundamentals of their businesses.

Can the market really be wrong?

The more investment time we have, the more skeptical we become with very abstract arguments, in which there is no clarity about the concrete factors and agents behind a thesis. Therefore, treating the market as an abstract and omniscient entity seems to us to be a bad idea. A first reason is that the price does not exactly represent the collective opinion of all investors about how much an asset should be worth, but rather the equilibrium point between supply and demand for that asset at that exact moment. The concepts are correlated, but not equal.

There are several reasons that can prevent an investor from constantly acting in accordance with his convictions. The most common is simply not having the capital available to act: if you believe that an asset is very cheap, but you do not have the liquidity to buy it, you will not participate in the day's price determination. If you need to consume capital for some reason (for example, covering operating losses), you may even be forced to sell assets that you consider cheap. In times of economic stability it is not common for several investors to find themselves in this type of situation simultaneously, but in times of crisis, exactly this is expected to happen and it becomes understandable that prices are no longer guided purely by intrinsic value analyses. .

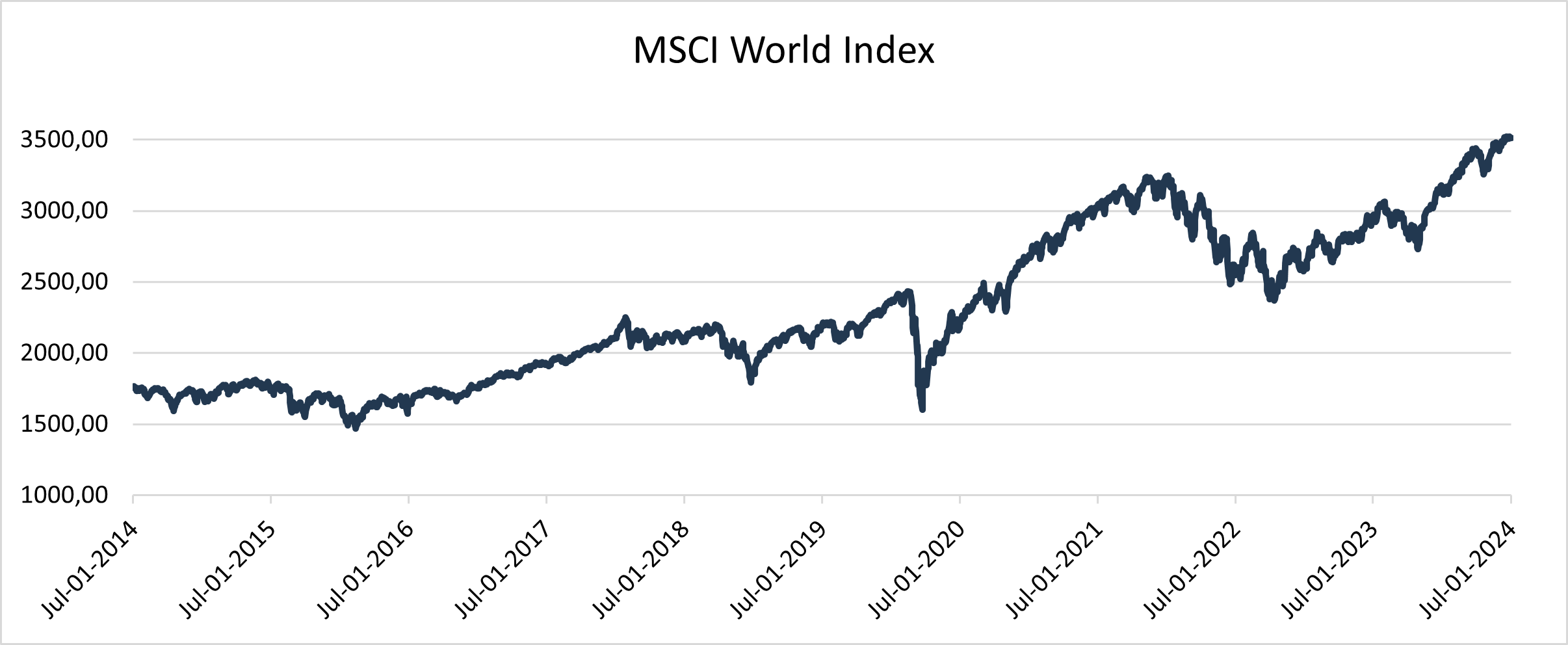

Another angle of view that corroborates the fallibility of market pricing is to observe how much the price of shares varies. The MSCI World Index is an index that considers the prices of approximately 1,500 companies from 23 developed countries, which represent ~85% of the total value of these countries' stock markets. In other words, it is broad and diverse enough to be a good representation of the global economy. The fundamentals behind this index, almost by definition, cannot be very volatile, since the global economy is an enormously complex system and very dependent on productive capital (infrastructure, factories, machines, etc.) and human capital (degree of qualification of people), two factors that almost never vary much over short periods. The types of events that could cause large variations are technological revolutions, in the positive sense, and global catastrophes on the order of magnitude of world wars, in the negative sense. However, this is the chart of the MSCI World Index over the last 10 years:

Not as stable as we might hope. Therefore, in the absence of a series of events of global proportions that justify such observed volatility, it seems more reasonable to consider that market prices are not always adequate representations of the real economic value of the assets they represent.

Admitting the possibility of the market being wrong at certain times, let's analyze the current Brazilian scenario and consider whether we are in such a moment. There are two central topics of concern among most Brazilian professional investors today: the global inflationary crisis and the way in which the current government has been seeking fiscal balance. Both topics are complex to analyze in detail, but we will provide a summary of what is currently said about it and our interpretation.

The impact of the global inflationary crisis in Brazil

The global inflationary crisis is not new. The BACEN (Brazilian Central Bank) began the movement to raise interest rates, the classic strategy to combat inflation, in March 2021. The Fed (Federal Reserve) began this movement in March 2022 and the ECB (European Central Bank) in July 2022. The most recent news is that the Fed decided to keep interest rates high for longer than the market initially projected, in the same way as we saw happening in Brazil. This has two main impacts.

The first is that, with higher American interest rates and concerns about the economy, many investors made the decision to migrate capital to American fixed income securities, seen as the safest among investment possibilities. From this migration comes selling pressure in several other asset classes, including our small Brazilian exchange, in which foreign investors currently represent around 55% of the total trading flow.

The second is that BACEN has been hesitant to lower the base interest rate, despite inflation in Brazil in the last 12 months (Jun/23 to May/24) being 3.9%, considerably below the average inflation of 5 .7% per year in the last 20 years. The argument presented by BACEN can be followed through the COPOM minutes, but it is well summarized in the excerpt “a scenario of greater global uncertainty suggests greater caution in the conduct of domestic monetary policy”. There is a huge controversy surrounding the interest level maintained by BACEN. As monetary policy is not our specialty, we will restrict ourselves to the observation that today the real interest rate is 6.6% per year, compared to the average of 5.1% per year over the last 20 years.

Our interpretation of these two factors is not positive, but it is milder than what we have heard from other investors. The selling pressure generated by the migration of capital to fixed income certainly affects share prices, but it has no effect on the intrinsic value of the Brazilian companies whose shares are being sold and, therefore, is a merely temporary factor, which does not change expectations long-term return. The extension of the contractionary policy by BACEN hinders the growth of companies and makes the financing available to them more expensive as long as interest rates remain high, so there is an impact on the real value of the businesses. However, the intrinsic value of each company is much more dependent on what the average interest rate is expected to be in the long term than on the discussion of whether BACEN will reduce interest rates a little more at the next COPOM meeting or in 6 months. In other words, the deterioration in value caused by a few extra quarters of high interest rates is on the order of a few percentage points, not dozens of them.

The desired Brazilian fiscal balance

Since the beginning of the Lula government, there has been tension around the issue of fiscal balance, so the context is well known: the public sector currently spends more than it collects, the so-called fiscal deficit, and the government has been resisting any initiative from the beginning of spending cuts. Thus, the way we have sought to achieve fiscal balance is through increased revenue.

The government's fundraising headquarters is also nothing new. We wrote in the October 2023 letter that we expected the tension around fiscal responsibility to persist throughout the Lula government and we continue with the same expectation, since the absence of fiscal austerity is based on the ideological conviction of leftist governments that it should be increase the public sector. The fact in itself already generates discomfort, as Brazil is not known for its low taxes and pressuring the productive sector with even more taxes does not seem to be the best path.

Furthermore, the way in which they have sought to increase revenue has been generating additional discomfort because, instead of admitting that they are increasing taxes, the government has made a statement that it is only correcting anomalies in the tax system, through changing rules. calculation and interpretation of tax benefits already granted. The practical result of these changes has always been to increase the effective rate, so there is clearly an increase in the tax burden and the discourse that denies this fact understandably generates distrust on the part of businesspeople and investors. Even more damaging is the uncertainty generated: what will be the next change and which businesses will be affected? The range of Brazilian sectors that have some type of tax benefit is enormous and, therefore, a large part of the economy can be the target of veiled tax increases.

On these points, we are aligned with the prevailing market view. We understand that this search for revenue through unpredictable changes to tax rules is harmful to the business environment in Brazil. However, it is not something that makes investments unfeasible. Our approach has only been to assume worst-case scenarios on tax matters when estimating the fair value of each business. It is also worth considering that the impact of an increase in taxation is not necessarily a direct reduction in the profitability of a business. As companies in the same sector usually enjoy the same tax benefits, a rule change impacts all competitors equally and the competitive position of each company tends to remain unchanged. The problem is that, if the tax increase is fully passed on to the price, the volume of demand is expected to decrease. Thus, the impacted sectors have to go through the dilemma of giving up growth or part of their profitability.

Is Brazil getting better or worse?

Anyone who invests in Brazil knows that there are rare periods when there are no controversies and political noise on the horizon. Therefore, a good dose of instability and systemic problems in our economy are already incorporated into the price level considered normal in our market. So much so that the average P/E multiple of the Brazilian stock market over the last 10 years is 10.3x, while this same multiple in the American market is 18.3x. Today, our stock's P/E multiple is at 7.5x. So, the question is: is the current scenario really that bad?

A year ago, IBOV was very close to the current price. At the time, the SELIC rate was 13.75% per year with 12-month accumulated inflation of 3.2% (i.e., real interest of 10.5% per year) and there was still uncertainty about how long BACEN would maintain interest rates at that level. GDP was expected to grow by 2.2% in 2023. The tax reform was still under discussion, with no clear prospect of approval, and the new rule for the spending ceiling was still open, with the expectation of a fiscal deficit.

Since then, the SELIC rate has fallen by 3.25% and real interest rates have fallen by 3.9%. GDP grew 2.9% in 2023, 32% above the projected value. Inflation remains under control, with a lower risk of rising again. Fiscal issues are still a problem, and are unlikely to stop being so soon, but we are relatively better off than we were a year ago. The tax reform was approved, although the details of how it will be implemented are still pending and we have a spending cap rule that, even though it is far from ideal, limits the growth of public spending and tends to work as long as the economy continues to grow. All in all, things have clearly improved over the last 12 months.

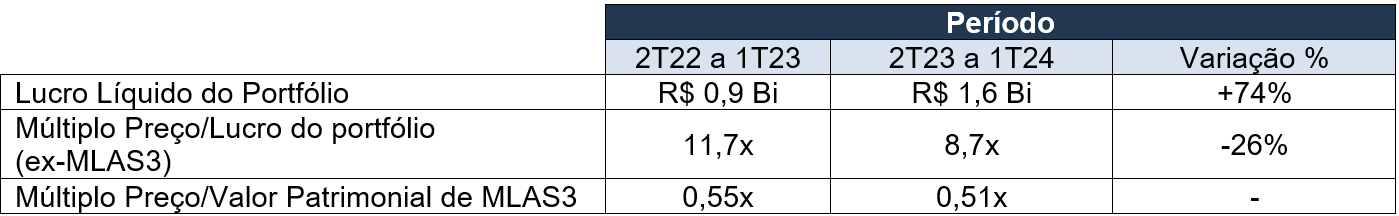

Even more important than these macroeconomic factors is the evolution of companies' results during this period. At this point, we will take the liberty of analyzing only what interests us: the profits and prices of the companies in which we invest through Ártica Long Term FIA. The comparison of the situation a year ago and today is summarized in the table below:

Due to this substantial improvement in the results of our investee companies, Ártica Long Term FIA has risen around 20% in the last 12 months. However, the Price/Earnings multiple of our current portfolio of Brazilian companies is lower than before. We segregated Multi (MLAS3) because of the negative net profit for 2023, which makes the Price/Earnings multiple meaningless, the Price/Equity Value multiple remained stable even with better prospects for the company today.

In other words, the fund is now cheaper than it was a year ago, in relative terms, even with the more favorable economic scenario and a clear trend of improvement in the operational results of the businesses we have in our portfolio. In the most careful analysis we carry out internally, in which we estimate the fair value of each of the invested companies and compare them with their market values, we currently have an atypically high discount level. We do not see anything that justifies this price level as adequate. It seems to us that these shares are simply cheap.

Still, there remains an argument that we have heard quite frequently: there is no expectation of any trigger that could make the stock market rise in the short term. However, when companies are doing well and their shares remain cheap, is it really necessary for some particular event to occur or is it enough for investors to notice the potential return implied by current prices and decide to buy again?

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.