Dear investors,

In order to try to draw parallels and understand potential implications for our investment decisions at this time of the pandemic caused by Covid-19, we decided to seek a historical perspective of how the capital market reacted in other periods of great crisis.

It is important to clarify that we are not analyzing, nor comparing, the dire humanitarian consequences of each of these past crises with the current one. What will become evident, however, is the enormous capacity of our society to overcome adversities and resume the course of economic growth.

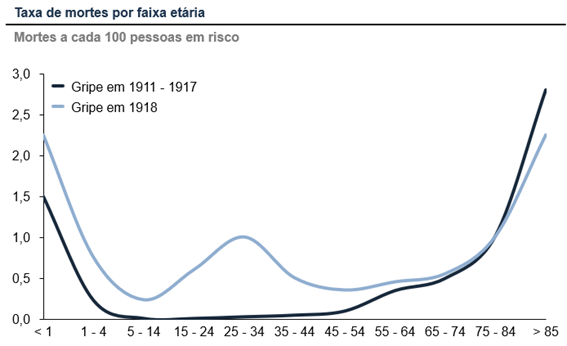

The Spanish flu infected one in four people worldwide, and is estimated to have killed about 2% of the world's population (that would be 160 million in today's numbers). Unlike flu waves in previous years, the 1918 flu disproportionately hit young people between the ages of 25 and 34[1], the main age group of the workforce:

As if that were not enough, this pandemic occurred between 1918 and 1920, at the end of the First World War, in which about 20 million people, including civilians and soldiers, perished. Whole countries lay in ruins. In terms of magnitude of loss of human life, this period is perhaps second only to that of the Black Death which peaked in Europe between 1347 and 1351.

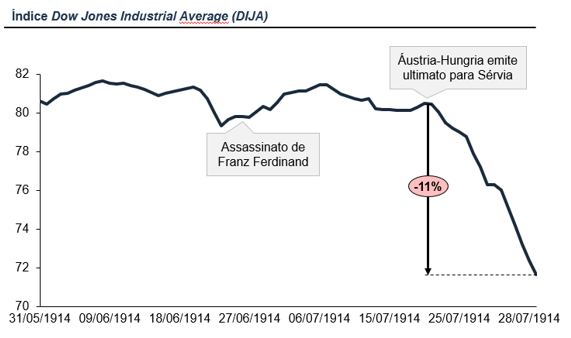

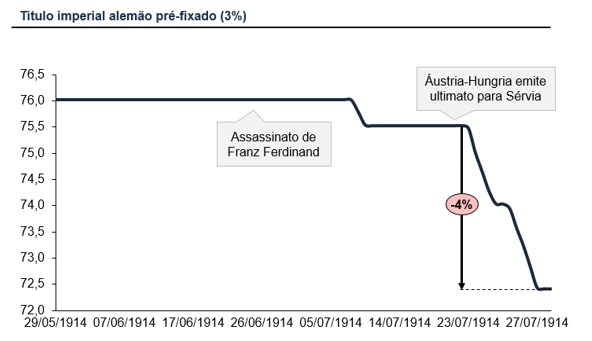

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 was the trigger for a series of events that culminated in the declaration of war by the Austro-Hungarian Empire against Serbia on 28 July. Germany declared war on Russia on August 1st, and within days the European nations were at war.

For nearly a month after the Archduke's assassination, financial markets did not react. Neither the value of shares in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) nor German government bonds seemed to price in the prospect of war. It was only when Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia that the markets panicked and started selling.

With the panic, the impact on global stock exchanges was immediate: the closure of all major European exchanges and many of the exchanges outside Europe, something that had never happened before. Other crises led to the closing of the stock market in the United States or in other countries, such as the Revolution of 1848 in France or the Panic of 1873 in New York, but the main stock markets in the world had never closed simultaneously.

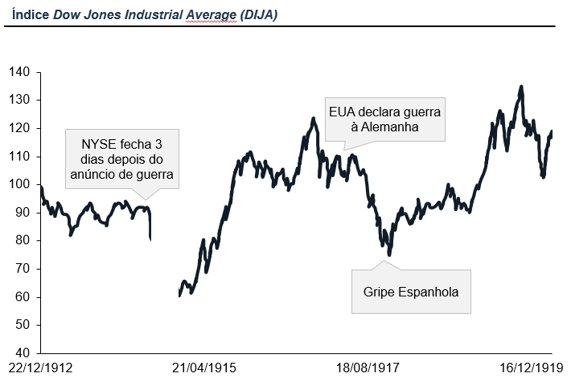

The NYSE was closed from July 30 to December 12, 1914.

Across Europe, the problem of catastrophic falls in stock prices was solved by putting a floor on stock prices. Initially, stocks and bonds were not allowed to trade below the price at which they traded on July 31, 1914. Governments also imposed restrictions on capital, limiting or preventing large capital flows out of the continent for the remainder of the war.

The Times of London began printing stock prices in London and Bordeaux on 19 September and in Paris on 8 December 1914. In January 1915 all stocks were allowed to trade on the London Stock Exchange, albeit with restrictions on price. The St Petersburg Stock Exchange reopened in 1917 only to close two months later due to the Russian Revolution. The Berlin Stock Exchange did not reopen until December 1917.

Obviously, it was a period of great volatility, in which the DJIA dropped from a level of around 90 points to ~60 at its minimum (~33% drop). Those who had calm and capital to invest in this period, and did not make hasty sales decisions, hardly lost money. The chart above does not include any dividends paid. Assuming reinvested dividends, an investor's return between January 1914 and January 1920 would have been 11.5% per year.

From a historical perspective, an investment in the DJIA in June 1914, on the eve of the war, maintained until today, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic and a generalized stock market crash, would have provided a return of 9.8% per year[2] in dollars (reinvested dividends), or almost 20,000 times the capital invested. In real terms, this is a gain of 6.5% per year above inflation for the period. It is worth remembering that this investment would still go through several other severe crises such as the crash of 1929, the Second World War, the cold war, the oil crisis, Black Monday, the September 11 terrorist attack and the 2008 global financial crisis.

World War II was the deadliest conflict in human history. Marked by 70 to 85 million deaths, most of which were civilians, it witnessed massacres, genocide (including the Holocaust), mass bombings, premeditated death from starvation and disease, and the only case of the use of nuclear weapons in a war until today. It begins on September 1, 1939, with the invasion of Poland by Germany, and ends on August 15, 1945, with the surrender of Japan, after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

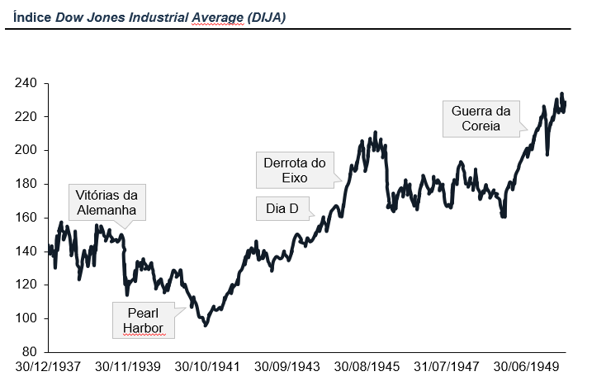

As we can see in the graph above, the DJIA followed the sentiment of the unfolding war: between 1940 and 1941, when everything indicated that the Axis powers would prevail, the unfolding of facts led the index to fall by around 33%. When the situation reversed, the index hit a high in which it more than doubled in a period of 4 years. A pre-war investment of USD 1,000 in June 1939 would have turned into USD 2,900 in June 1950, an average real return of 4.8% above inflation for the period.

Governments and stock exchanges learned their lessons from the First World War. When World War II broke out, the London Stock Exchange closed for only a week and the New York Stock Exchange never closed, except on August 15th and 16th, 1945 when the NYSE closed to recognize the end of the war. The Berlin Stock Exchange remained open throughout World War II, although minimum price policy and capital restrictions prevented stock prices from falling until the 1948 devaluation.

Finally, we bring a Brazilian perspective, presenting what was, perhaps, the worst period to date for our exchanges.

On the morning of March 16, 1990, the day after assuming the presidency, Fernando Collor de Mello announced a series of provisional measures to try to contain the hyperinflation that in 1989 had been almost 2,000%.

The most striking fact of this plan was the confiscation of savings: of all the money deposited, only 50 thousand new Cruzados could be converted into Cruzeiros and redeemed, while the rest would be blocked for 18 months. According to the commercial dollar exchange rate on the Monday following the announcement of the plan, the 50,000 new Cruzados would be equivalent to just over a thousand dollars.

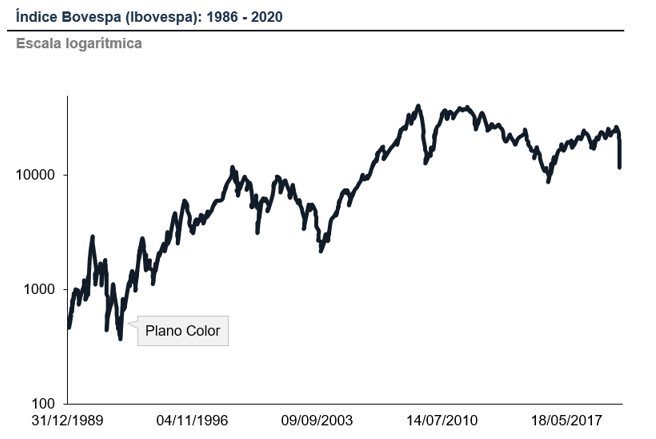

Uncertainty about the future and the need to redeem money to cover the amount blocked by the Government led to a series of curious facts in the following trading sessions. Due to the lack of liquidity, in the trading session of Monday, the 19th, the now defunct Rio de Janeiro Stock Exchange did not record any trading! Likewise, Bovespa would only have 9 trades (out of curiosity, 8 of them with Paranapanema shares, whose shares devalued by 49.7%.) On that day, the Ibovespa had a drop of 12.1%.

On Tuesday, with a slightly higher number of trades – there were 36 –, the Ibovespa recorded its biggest daily drop so far, of 20.9%. But it was the following trading session that went down in history as the index's biggest daily devaluation: 22.3% down, with 142 trades and a still very low financial volume of Cr$ 1.76 million. As a basis for comparison, the trading session prior to the announcement of the Collor Plan recorded a financial volume of NCz$ 1.33 billion, with 4,795 trades.

In just 3 days, the Ibovespa dropped 46% and, in dollars, an incredible 72.7% in the year (the best reference due to the hyperinflation that was not curbed and accumulated an increase of 1,700% in the year).

GDP fell by 4.3% in 1990, according to the IBGE – which at the time used a slightly different methodology to calculate national accounts.

To illustrate, let us think of a very “unlucky” investor who had invested in the Bovespa index before the announcement of Plano Collor, buying the index at 1,000 in dollars, and selling now, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, with the Ibovespa close to 12,000 also in dollars, would have a nominal return of 8.6% per year in hard currency. It's not a return to be proud of, but we're talking about getting in and out at the worst possible times.

By investing in the stock market, we are, in a way, investing in the human capacity to innovate and generate prosperity for society. The excellent appreciation of stock indices over the last 100 years has been accompanied by a significant improvement in the quality of life of the population. Today, a middle-class person lives better than the richest did 100 years ago.

We are fully aware of the unpredictability of the unfolding of the current crisis, and we hope that we can get out of it as soon as possible. But we are quite confident that the future of society and our investments will be better than the scenario we were in even before the Covid-19 crisis appeared without having to wait 100 years for that.

“The present is the past rolled up for action, and the past is the present unrolled for understanding” – Will & Arial Durant, The Lessons of History, 1968

[1]Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (January 2006). “1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics”. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12(1): 15–22.

[2]https://dqydj.com/dow-jones-return-calculator/