Dear investors,

It is a natural tendency to pay more attention to things that suddenly impact the world. Technological revolutions, wars and major political events are what make headlines. Meanwhile, slow but persistent movements over decades generate silent revolutions. As in the fable of the race between the hare and the tortoise, consistency can take you further than speed.

We will address one of these silent revolutions. There are two clear demographic trends that have been observed in many countries: fewer and fewer children are being born and people are living longer and longer. Within a few decades, we will inevitably have more old people and fewer young people. This will have a profound impact on the economy, which will have to adapt to a different profile of the population available to work and to consume.

We imagine that this is not a new topic for anyone, but, like everything that seems very distant, it is unlikely to be at the top of most people's list of concerns. However, change is not far off. It has been happening for decades and will continue to advance day by day. The aging of the population is as liquid and certain as its own cause: the passage of time.

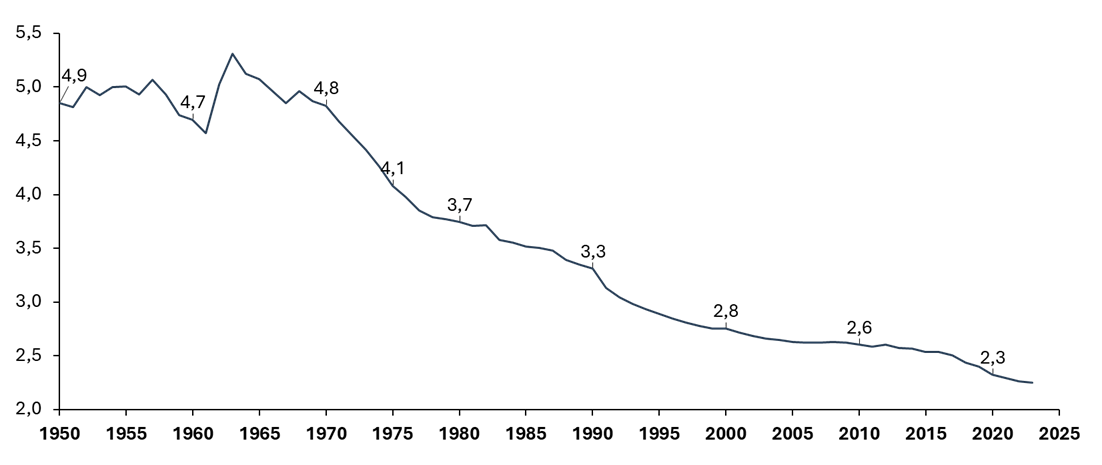

Decline in fertility around the world

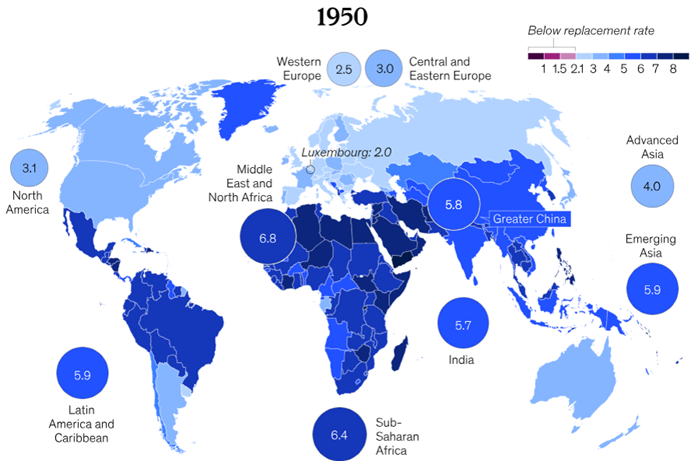

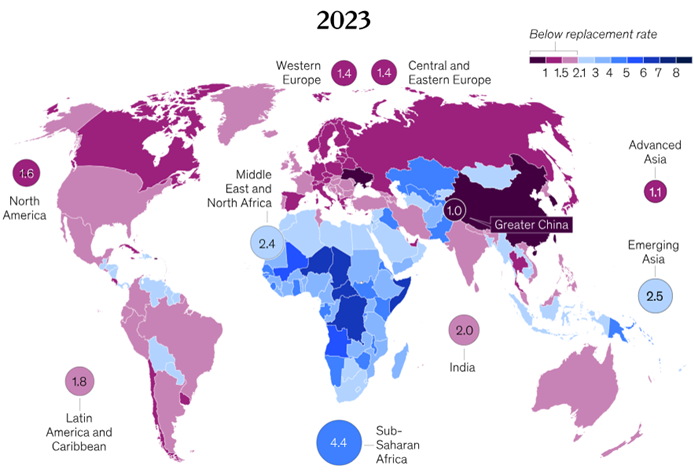

To maintain the population, women need to have an average of 2.1 children over their lifetime. Today, the average fertility rate in the world is 2.3, slightly above the replacement rate, but with a very uneven distribution. The underdeveloped world still has high fertility rates, while countries where two-thirds of the world's population live already have fertility rates below the replacement rate, including all developed economies on the planet.

The decline in fertility is not a recent phenomenon, but it has been quite abrupt from a historical perspective. In just over 60 years, global fertility has fallen by half. The graphs below put into perspective the magnitude of the change over the past few decades.

Global fertility rate (children per woman)

Source: UM WPP (2024), HFD (2024) –ourwordindata.org/fetility-rate

Fertility rates around the world – 1950 and 2023

Source: Mckinsey & Company – Dependency and depopulation: Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality

The change in the demographic profile is a direct consequence of the decline in fertility. The increase in life expectancy has some contribution, but approximately 80% of the phenomenon is derived from the number of children born each year.

The demographic profile will advance in a very predictable way due to an obvious fact: the number of people over 65 years old that will exist in the world in 2035 depends only on the number of people aged 55 years old alive today and the mortality rate, a stable statistical indicator. Thus, the fertility curve of the last decades determines the demographic profile of the coming decades in a completely irreversible way.

For future generations, the problem could be addressed by increasing the fertility rate. In theory, this would be feasible. Several countries with fertility rates below replacement have tried to encourage couples to have more children by offering financial support, tax breaks, and longer periods of leave after each birth. However, no country has yet succeeded in restoring its fertility rate to the required 2.1. As a result, the demographic change that is coming is inevitable.

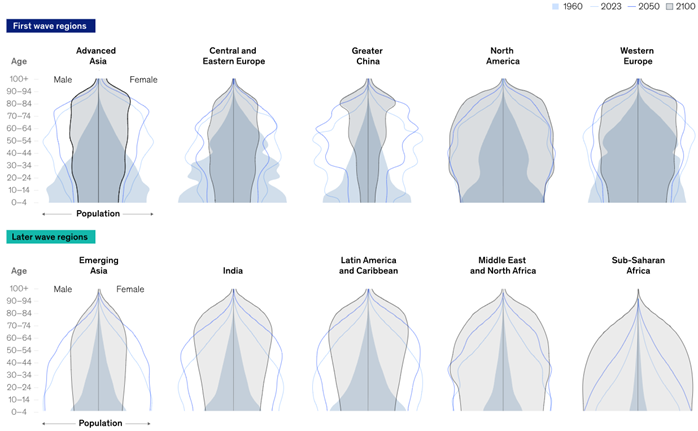

Changing demographics around the world

Source: Mckinsey & Company – Dependency and depopulation: Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality

Economic phases of life

To assess the impact of changing demographics on the economy, we need to make some simplifications. We will outline the situations and behaviors that have the greatest economic impact at each stage of a typical middle-class person's life, so that we can understand what will change as the number of people in each of these stages evolves over the years.

From birth until adulthood, people do not have significant economic productivity and are dependent on their parents. They consume little, due to the more limited range of needs during childhood and the lack of autonomy in consumer decisions. The largest category of expenses in raising children is education, at least in countries that do not offer quality public education. The rest of the demands tend to revolve around basic living expenses.

From the beginning of adulthood until about 35 years of age, the first phase of adult life, the focus is on building a professional life and forming a family. This is a phase in which income tends to increase, but little is invested because expenses increase in parallel. In addition to expenses related to the “infrastructure” for life: housing, cars and a variety of personal goods, this is the first phase in which people begin to have more money and can decide for themselves how to spend it. With retirement still a long way off, it is more common to indulge consumer dreams than to invest with old age in mind. After marriage and the birth of children, a new wave of costs related to raising and educating comes. The couple continues to consume a good part of their income while trying to advance in their careers and increase their income, since this is a phase in which it is difficult to control consumption.

The next phase is full maturity, typically between the ages of 35 and 55. This is when people generally reach the peak of their professional life and their income reaches its maximum level. Consumption increases accordingly and with a greater variety of destinations, since basic expenses are no longer so important. It is during this phase that discretionary consumption increases: travel, restaurants, and occasionally some luxury items. If children go to private universities, education may continue to be a significant expense. This tends to be the time when spending also reaches its maximum level. Even so, it is the time when more significant investments begin to be made, when income levels allow.

From age 55 until retirement, usually around 65, is a phase in which income remains high and basic expenses tend to fall. Careers are already well established, several assets have already been purchased and children are becoming independent. Some take advantage of the budget slack to increase personal spending and may indulge in some extravagances, but concerns about retirement become more evident and there is economic capacity, so this is the phase in which more investments are made.

Retirement is a significant milestone in economic life. Most people do not have full-time pension plans, so their salary drops or, at worst, stops altogether. The consumption profile tends to change significantly. Work-related expenses (transportation, clothing, eating out) cease and health care expenses increase. Some decide to simplify their lives, reduce recurring expenses and dedicate a larger portion of their budget to other purposes. For example, they may move to a smaller house, adopt more frugal habits and, at the same time, spend more on tourism or other leisure activities that were part of their retirement plans. Up until about age 75, people are considered “young-elderly” and can remain quite active, so the level of spending may not drop as much. On the other hand, investments tend to decrease significantly and the risk profile migrates to more conservative assets. The phase now is to consume what has been saved up to that point, taking care not to exhaust all the capital before the end of life.

From the age of 75 onwards, consumption levels tend to drop. People are no longer as willing to travel or do many activities, so life tends to become more focused on family and domestic routines. This is the phase in which health expenses become higher, but the rest of the budget goes back to covering only the basic costs of living. People start to think about what to leave to their children and may even make transfers while they are still alive. Investment profitability is no longer the focus and the main concern is capital preservation.

With all the necessary caveats for a summary of the entire life cycle on one page, this schematic view allows us to reflect more clearly on the main changes caused by the aging of the population.

Job market

Roughly speaking, a country’s economic output depends on its active labor force, the number of hours worked per person, and its level of productivity. A first indicator to look at is the percentage of the total population that actually works. Global standards consider the productive age to be between 15 and 64 years, so the higher the percentage of the population in this age range, the greater the economic potential of a country. The maximum share is around 70%, but population aging tends to reduce this indicator to somewhere between 50-60% in most countries.

The countries that experienced the decline in fertility rates first have already passed their peak population of working age. This group includes most European countries, the United States, China and Japan, which is currently the most advanced country in terms of changing its demographic profile and has been the case studied to predict the impacts of population aging. Most of the other countries, including Brazil, will reach their peak and begin their decline at some point in the next decade.

The first impact is the shortage of young workers, which mainly affects activities that require low-skilled labor. This phenomenon is already quite noticeable in several countries, and most of them have been resorting to immigration to fill the gaps that have emerged. One exception is Japan, which has resisted massive immigration and has suffered the most from the shortage.

The alternatives to immigration are difficult: either increase productivity or increase the per capita workload. Increasing productivity has been pursued with some success through new technologies such as artificial intelligence, factory automation and robotics. Increasing the per capita workload is a more difficult move. In theory, most countries have room for this, when compared to the Chinese workload, but their populations are not sympathetic to the idea and strongly resist any attempt to change in this direction. Immigration also has its problems, but we will avoid the subject so as not to lose focus.

If none of this is done, the consequence will be an economic recession. We do not see this as the end of the world, since quality of life depends much more on GDP per capita than on GDP growth itself, but it would be breaking dogma to accept that the economy will no longer grow, so efforts have been made to find a way to prevent this from happening. This is not a trivial goal. Japan – a small, developed country with an atypical level of general discipline – has only managed to keep its economy more or less stagnant for three decades.

Even maintaining GDP per capita is not obvious because of the falling percentage of the working-age population. At the peak of 70%, there are 2.3 working-age people for every young person or retiree. At the projected 50% for some countries, there is only 1 working-age person for every dependent. This is a heavy burden to carry, and there is a limit to how much workload can be increased, so the world will rely heavily on productivity increases to avoid a decline in the average quality of life.

Social security problem

There is another problem that is more complex and politically charged than the issue of available labor. Several countries, including Brazil, have structured public pension systems that have not actually invested the contributions of the first generations of participants, trusting that the contributions of future generations would be sufficient to finance the payments due to retirees. However, demographic trends will increase the number of retirees, beneficiaries of public pensions, for each active worker, contributor to social security. The direct consequence is that there are only two alternatives: contributions will increase or benefits will be reduced.

The increase in contributions could, in theory, be done by the government itself, but most governments with pension problems also have fiscal balance problems. So, it is more likely that they will increase taxes, increase the contribution period (postponing the retirement age) or adopt both measures, however unpopular they may be.

Reducing retirees’ benefits is an even more sensitive issue, understandably. People plan according to the pension terms that were offered to them (or imposed by law) and make their contributions throughout their lives. Reducing their benefits after retirement, when they are no longer able to work and have great difficulty in reorganizing their lives, is a tremendous injustice. However, there is no painless alternative.

This discussion is likely to generate a potential conflict between generations, as the extra efforts fall on the young population, which already has the expectation of contributing more than it will receive when it is their turn to retire. Young workers are forced to adhere to a pension system that is clearly a bad deal for them, and implementing changes is not politically easy, as there will be an increasing number of voters in age groups who are in favor of maintaining pension benefits.

Governments will probably resort to hybrid solutions that include all the alternatives: reducing benefits, increasing taxes and extending the contribution period. The last option seems the most palatable to us. One possibility would be to adopt a few extra years of work with reduced working hours, since life expectancy itself has been increasing. But we do not have the ambition to predict what the political decision will be in each country.

The Brazilian case

Brazil is in an intermediate demographic range. Our population continues to grow and is expected to peak around 2040, but the Brazilian fertility rate in 2023 was 1.6 children per woman, already below the replacement rate. The slow population growth that is still expected comes from the increase in life expectancy. The working-age population will peak a little earlier, around 2035, but growth until then will be only 1.6%, with no further significant demographic bonus from now on.

Projection of the Brazilian population (millions of people)

Source: IBGE, Arctic analysis

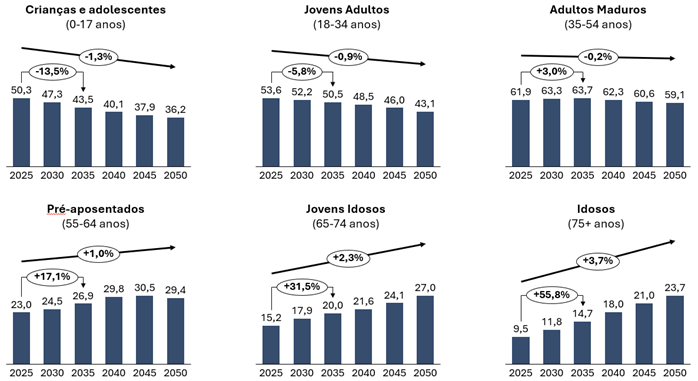

The most significant impacts for Brazil will come from changes in the demographic profile. We have adapted the IBGE projections to fit them into the age groups according to the life stages described above. This way, we can interpret the data in a qualitatively more relevant way to reflect on possible consumption and investment scenarios in the country.

Projection of the Brazilian population by age group (millions of people)

Impacts on the Brazilian economy

The most obvious impact of demographic change is on Brazil's consumer profile. Sectors that target children, teenagers and young adults are likely to face growth difficulties going forward. The most striking example is the education sector, especially in the elementary and secondary education segments, as the number of children and teenagers will fall by 14% in the next 10 years. Other examples of sectors that will be affected include toys and games, clothing and accessories brands aimed at teenagers and youth entertainment, such as nightclubs, festivals and the like.

Sectors focused on the over-35 demographic will benefit, especially in the older age groups. The elderly population will grow by 41% over the next decade, equivalent to a constant compound growth of 3.5% per year. This is a significant growth boost for the healthcare sector, for example. As a reference, people over 65 spend around 3 times more on healthcare than people under 25. Tourism and leisure activities suitable for the older public will also benefit from the greater number of retirees, with time and money at their disposal. Premium brands and luxury-related sectors are also likely to benefit, as the age groups that tend to have more room in their budgets for this type of spending will expand.

For the same reason, the financial and wealth management industry is expected to grow, driven by the 17% increase over the next decade in the number of people in the pre-retirement phase, when a larger portion of their income is invested. Mature adults, another target age group for the sector, will grow by only 3% over the period, but will still contribute positively.

Services and products linked to productivity gains should accelerate their growth. The shortage of young workers will stimulate increased investment in this direction, as it should inflate wage levels and make automation and related technologies more economically favorable, which may not be worth it until labor becomes more expensive.

There are sectors in grayer areas. The end of the population growth period should also imply a stagnation in the expansion of urban infrastructure, but this reasoning assumes that what exists today is sufficient. Brazil still has areas that would need significant investment to reach the recommended level for the current population, but this deficit is typically linked to the lack of economic capacity of these locations, so it is not obvious that expansions will happen. In Japan, where the population is decreasing, there are places where there are houses left over. Real estate prices in these regions have been falling and the construction industry has been focusing on renovating old buildings.

A less obvious impact is that the risk premium on investments in general tends to increase, as older people will represent an increasingly larger share of the total capital invested in the market and risk aversion tends to increase along with age. Another possible effect is that the basic interest rate tends to fall, due to the greater abundance of capital seeking low-risk fixed-income securities and the slower pace of economic growth, resulting from lower demographic growth, which reduces the demand for capital and, thus, interest rates. This has happened in Japan and the European Central Bank makes the same prediction for the European Union (The macroeconomic an fiscal impact of population ageing, 2022).

Impact on equity investments

For the stock market as a whole, the future is uncertain. On the one hand, the fall in interest rates would cause assets to appreciate. On the other hand, the increase in the risk premium would go in the opposite direction. Despite this uncertainty, this general effect seems to us to be much less relevant than the sectoral effects such as those we have illustrated. We believe that several good opportunities will arise for those who know how to reflect on how the aging of the population affects each business in particular and have the patience to wait for the effect of this slow but deterministic change.

We currently have approximately 25% of our portfolio in investment theses that benefit greatly from population aging: Fleury and Blau, in the healthcare sector, and Banco Mercantil, which offers financial services specifically for the over-50s. This percentage is expected to increase soon, as we recently approved an investment in a Japanese healthcare company. We plan to share more about the deal once we have achieved our desired portfolio allocation.

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.