Dear investors,

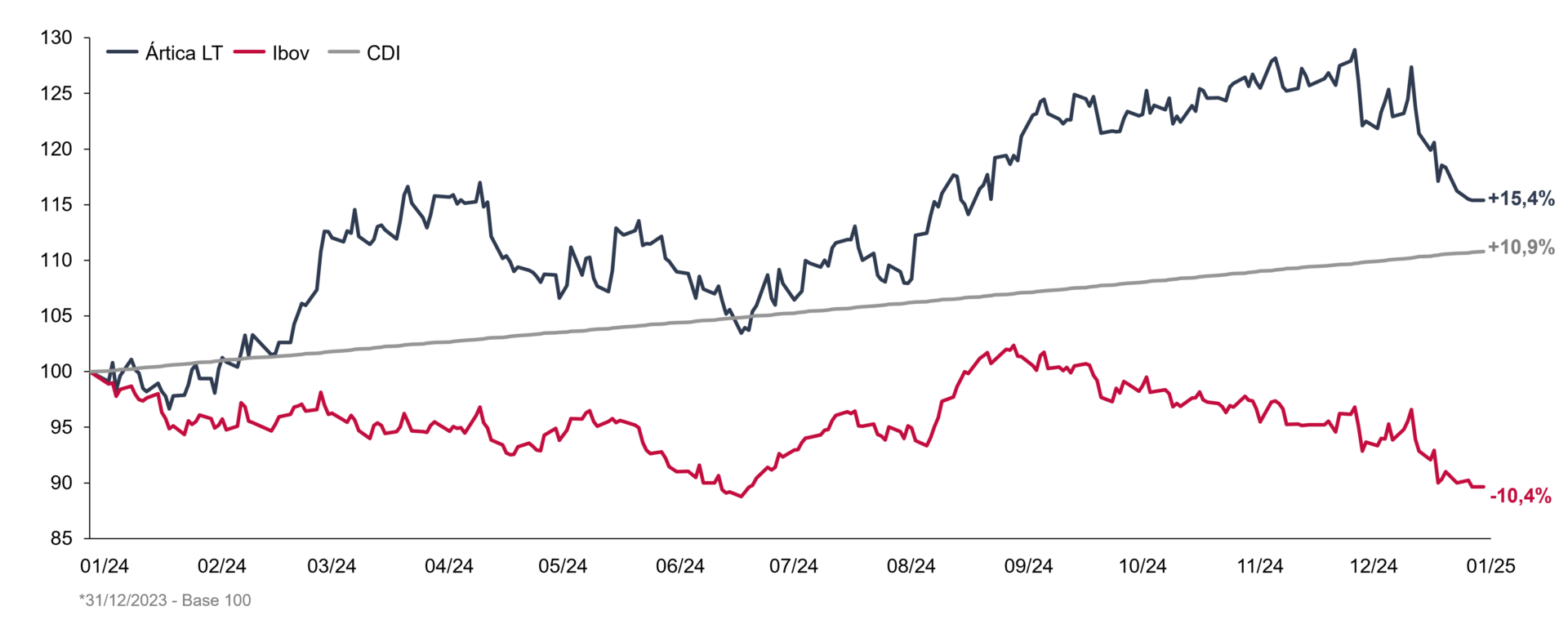

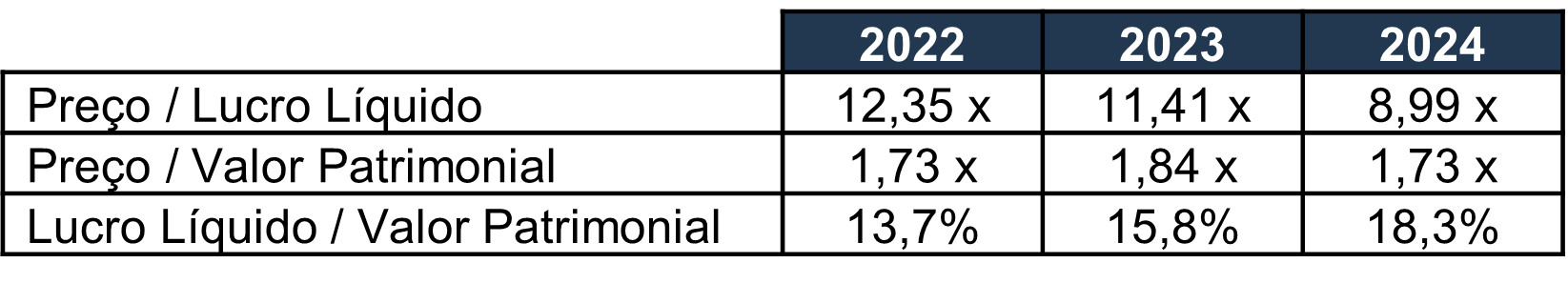

The IBOV ended 2024 with a return of -10.36%, reflecting the market's bad mood with variable income that has been going on for several months. Most investors have been migrating their capital from variable income to fixed income, attracted by the SELIC already at 12.25% and with forecasts of reaching 14.25% in the coming months. The movement has been interpreted as an obvious strategy in the current context.

In parallel, Ártica Long Term ended 2024 with a return of +15.40%, above both the IBOV and the CDI.

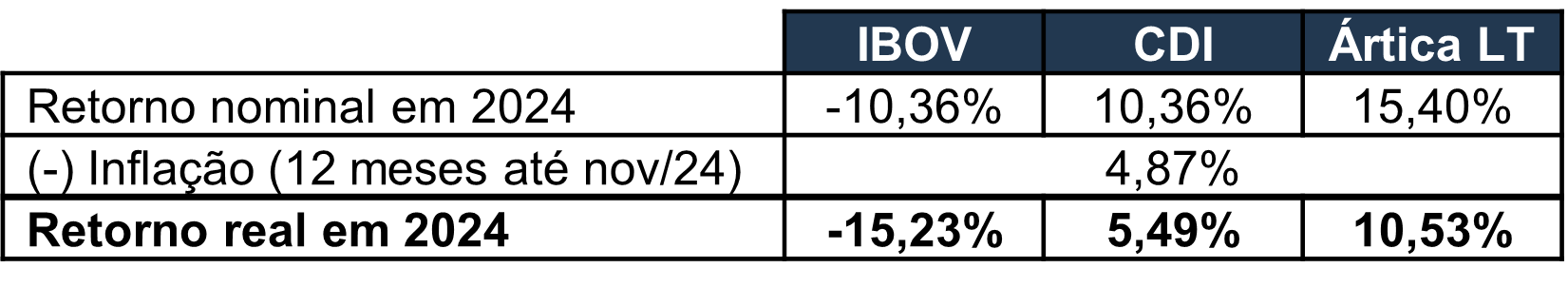

Comparing the real rate of return of Ártica Long Term and the indexes, the difference in additional purchasing power generated for our investors becomes clearer:

Return comparison in 2024

The result raises concerns that the prices of the shares in our portfolio have risen more than they should have and may now be expensive, but this impression is dispelled by a quick analysis of how the weighted averages of the multiples and profitability of the shares in our portfolio have evolved in recent years:

Average multiples of the Ártica Long Term FIA portfolio

Note: Weighting by portfolio share at the end of 2024. To calculate 2024, the results of the 12 months up to 3Q24 (latest available to date) were considered. MLAS3 was excluded from the P/E analysis due to losses in the period.

The price increase came purely from an increase in the profitability of our companies. In relative terms, prices fell. The P/E multiple for 2024 was 27.2% lower than that of 2022. So, we pose the following provocation: investing in companies that have been improving their results, but still have their shares falling in price, in relative terms, does it seem like a good or a bad idea? Better or worse than the CDI?

Let's take a step back to look at the situation more conceptually.

Fixed income and variable income prices move in the same direction

There is a strong bias towards focusing on data that is most readily available. As a result, we follow stock prices and the annual rate of return on fixed-income securities. This creates confusion because every asset has both a price and an expected return, and these indicators are inversely proportional. If a security yields R$ 100 per year, this return is equivalent to 10% of the amount invested if the security's price is R$ 1,000 and to 20% if the price is R$ 500. In other words, the lower the price of the same asset, the higher its expected rate of return should be, and vice versa.

In fixed-income securities, the rate of return is determined and the price of the security varies freely. When the rates of return offered in the market are rising, it means that the prices of the securities are falling. In stocks, the same logic applies: when prices are falling, it means that the expected rates of return are rising. So, there is an incongruity in being excited about fixed income when the rates of return rise (and prices fall), but being discouraged about stocks when their prices fall (and expected rates of return rise).

Post-fixed securities, although also classified as fixed income, have a fixed price and variable rate of return. This is similar to a stock with a fixed price. In this case, it makes sense to be excited when interest rates rise, but this type of security carries a reinvestment risk, since high interest rates now do not guarantee good profitability throughout the maturity period. If interest rates fall, the option would be to sell the post-fixed securities to buy something else, but it is expected that the price of stocks and pre-fixed securities will have already risen during the fall in interest rates.

Having clarified the confusion created by the convention of following inversely proportional indicators, let's get to the point of why interest rates are rising in Brazil.

Interest, inflation and the impact on the real economy

Throughout 2024, we have been following the clash between the government, which is suffering from high interest rates on public debt, and the Central Bank, which says that high interest rates are necessary to combat inflation. We wrote about the dynamics between government spending, inflation, and interest rates in our September 2024 letter. For our current purposes, it is enough to recall that the interest rate hike projected today is justified by the diagnosis that the Brazilian government is overspending, as this contributes to rising inflation and requires the central bank to raise interest rates as a counterbalance.

In addition to the problem of increasing public spending while fighting inflation, the Brazilian government is running a deficit. Excessive spending causes the public debt to grow even more and also increases the risk of government bonds. Governments that have debts in their own currency do not default on their payments, but they can force the Central Bank to arbitrarily issue more currency (print money) to pay the debts, generating inflation.

The practical effect of this process is that the government appropriates part of the capital of those who have assets backed by the national currency (fixed income securities in reais) and distributes this capital to the beneficiaries of public spending. This last point has been less discussed. Government spending always ends up in the pockets of public employees and companies that provide services to the government, which, in turn, have their own expenses with people and companies not directly related to the government. In other words, the primary impact of financing public spending through inflation is negative for those with fixed income and positive for the real economy.

The side effect that harms the private economy is the rise in interest rates, which increases the cost of corporate debt and reduces the availability of credit for consumption, cooling demand. However, these effects are not distributed equally among companies. Companies that are in debt and have no connection with consumer chains fueled by government spending are harmed, while those that are debt-free and operate in sectors with demand fueled by public spending can benefit.

Two conclusions can be drawn immediately. The first is that variable income encompasses companies from such diverse sectors that any generalization about the category is usually quite flawed. The second is that it is not obvious to consider fixed income a safer investment than stocks when the problem is a government deficit and accelerating public spending.

Another point in favor of stocks is that real assets do not have their value eroded by inflation. Fixed-rate securities will certainly lose value in an inflationary environment, but companies will not, since their value is made up of operations, various assets, intellectual property, etc., which have an intrinsic economic value. If the currency loses value, the price of this set of assets rises so that the real economic value is preserved.

This does not mean that a scenario of excessive government spending is desirable for those who invest in stocks, because the long-term impact of deficits and inflation is to reduce confidence in the government, drive away foreign capital and reduce the country's productivity, since the government's capital allocation does not have economic efficiency as its main goal. However, it is better to own stocks than fixed income securities in this scenario. The recent stories of Turkey and Argentina are practical examples of this statement.

In Turkey, inflation due to excessive government spending was already high for some time (15-20% pa), but it got out of control in 2022 (peak of 85% pa) and remains high to this day (~50% pa). However, the Turkish stock market rose by 29% pa in US dollars from the end of 2021 to the end of 2024. In Argentina, in the 5 years prior to the entry of the Milei (2019-2023), average inflation was 79% pa. During this period, the Argentine stock market rose by 19% pa in US dollars.

What is the chance that the macroeconomic scenario projected today will materialize?

Keynes said that economic projections were always made by extrapolating the current scenario into the future, except for specific effects that were predictable with reasonable confidence, even knowing that the premise of continuity of unpredictable factors is highly unlikely to materialize. For lack of an alternative, the practice became a convention and the process of valuing assets was considered correct if done in this way. The observation is made in the book General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936, and the same practice remains unchanged to this day.

The convention is old, but it has not become more efficient over time. Macroeconomic projections are notoriously unpredictable precisely because of the number of random factors that are implicitly considered constant in them. Just remember how much the narrative of what the near future would be like has changed over the past year. Looking at a longer term, it is clear that this was not an exceptional year. Forecasts change all the time, as new facts materialize, and the accuracy rate of any macroeconomic theses is quite low.

Consensus on macroeconomics often ends up becoming collective errors. Even so, a large number of investors consider the prevailing theories at the moment as key factors in making capital allocation decisions, which seems to us to be an unadvisable approach because, in addition to the history of errors, nothing that is being widely publicized could be an informational advantage that would lead to better decisions than the market average. If it's in the newspaper, it's already in the price.

We prefer to maintain the intellectual honesty of admitting that we do not know what will happen with interest rates, inflation, the fiscal policy of the Lula government or any other of the traditional macroeconomic variables. But this is not a new situation. We have never had good predictions about things of this nature and we have still managed to get good returns. The key point was made a long time ago by Warren Buffett: there are important factors that can be predicted and factors that are also important but impossible to predict. The best allocation of time is to worry about what is predictable, rather than wasting effort on what is unpredictable.

The good old investment strategy

When the environment is turbulent and confusing, a good practice is to go back to basics.

Companies have value because they offer a product or service that society wants to consume. This value could be lost if demand is reduced or captured by competitors. Therefore, a defensive portfolio should focus on sectors where demand is stable and on companies whose competitive position is sustainable.

If interest rates are unstable, high debt levels can cause negative surprises in financial expenses and can affect the company's ability to continue investing and operating at competitive rates. Therefore, it is prudent to avoid highly leveraged businesses in unstable scenarios.

The last principle is to buy cheap, to offset any negative surprises that turbulent economies may bring. This step should be the most difficult to execute for companies that meet the previous criteria, but it is quite common for stock prices to fall together when market sentiment deteriorates in Brazil. It is likely that part of the explanation comes from the volume of investments linked to foreign investors, multimarket funds, index funds and quantitative funds, which typically do not perform in-depth fundamental analyses on each company and, in aggregate, must account for more than 70% of the B3 trading flow (there is no detailed data to confirm the exact percentage).

We are among a minority of investors who still follow the old strategy of evaluating each opportunity based on its long-term fundamentals. Even fewer are those who truly admit ignorance about the macroeconomic future and focus only on the microeconomic factors of each business.

Our current portfolio was built according to these few basic principles. We invest in companies with sustainable competitive advantages, in sectors with stable demand, and that are cheap on the stock market today. The market volatility throughout the year has simply caused us to rebalance some positions at certain times, and the rather abrupt stock market crash in December has allowed us to invest in shares of companies that we have been coveting for some time (we will discuss the new positions with Ártica Long Term investors at the next quarterly earnings call).

We share the general apprehension about the situation in our country, but we remain optimistic about the return potential of our portfolio of companies, handpicked to face Brazil's uncertain future, and we believe we have a good chance of continuing to outperform the CDI in the long term.

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.