Dear investors,

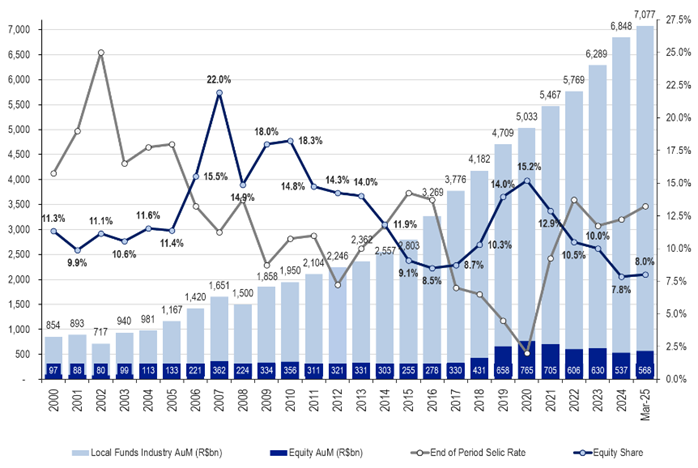

The Brazilian stock market has been losing space in the portfolios of local investment funds since 2021. Today, 8.0% of the total capital managed by funds is invested in variable income, very close to the lowest level in 25 years (7.8% at the end of December 2024) and well below the average of 12.7%.

Local equity fund allocations (R$1.4T billion)

Source: BTG Pactual – Brazil: Follow the money, May 13th 2025.

The main reasons for the low allocation are in the newspapers almost daily: concern about the fiscal deficit, the growing debt of the Brazilian government and high interest rates, which encourage the current motto of the Brazilian investor: why take risks on the stock market in this scenario and with the CDI so high?

The motto is reinforced by recent history: from January 2021 to May 2025, the IBOV yielded ~17% while the CDI yielded ~55%. Added to the fact that investment decisions in variable income are always more complex than simply investing in post-fixed securities and observing the constant progression of your assets, it is fair to question why it would make sense to invest in the stock market in Brazil now. Meanwhile, Ártica's funds are almost completely allocated to stocks, so we are expected to have an answer.

Our first point is that stock market investments are not destined to return on the IBOV. There is much more room to obtain additional returns, through asset selection, on the stock market than in fixed income. Investors in Ártica Long Term FIA had a return of 74% (1.35x the CDI) in the period in question, even with the tide against stocks. The broader reasons to invest in stocks now are that companies are structurally biased to yield more than credit investments and the best way to seek good returns is to buy when there is low capital allocation in the stock market, since this is precisely when it is undervalued. Let's explore these points.

The average return of companies needs to exceed the CDI

The original sources of economic value are natural resources and human time spent on something that has immediate (services) or future (consumable products, capital goods, and technology) utility. Since there are infinite ways to organize the use of both, and attempts to do so in a centralized manner have been famously unsuccessful, the main advantage of the modern capitalist system is to create incentives for the constant and decentralized pursuit of the best possible organization through a self-calibrating price system: the well-known mechanism for determining prices by balancing supply and demand.

The classic example of how productive activity is organized based on this price mechanism is that any good will be produced more soon after demand for it increases, since the emergence of demand above the available supply will cause prices to rise, which will encourage the creation of additional supply capacity to restore equilibrium. The same logic works in reverse, and the optimization of capital use follows the same principle, from a slightly altered angle of view: when demand for something rises, the rise in prices causes the capital allocated to create additional supply capacity to have the expectation of higher returns, so there is an incentive to allocate more capital for this purpose until supply and demand are rebalanced and the return premium that existed until then disappears.

Fundamentally, credit is not necessary to solve the capital allocation problem. All investments could be made directly in companies and each investor would directly experience the risk of the economic activities they decided to encourage by making their capital available. The benefit brought by the credit mechanism is to provide greater capital mobility in the economy. Instead of having to deeply understand the expected return of a sector and make the decision to invest in it for an indefinite period, given that the sale of shares in a privately held company is a complex process, it is possible to outsource much of the problem to someone who already understands the sector that requires capital and already has an allocation plan in mind. The owner of the capital makes a loan under terms that are much simpler to analyze: a pre-determined rate of return and payment schedule, and a structure of guarantees to reinforce the borrower's commitment.

The benefit to the creditor is clear. For the entrepreneur, it only makes sense to take out loans if the agreed interest rate is considerably lower than the expected return on the use of the capital, since the risk is disproportionately on his side. Of course, in many cases borrowers make mistakes and end up worse off than their creditors, but if this negative outcome becomes too common, entrepreneurs will start to borrow less capital, opportunities for investment in credit will become scarcer than the capital available to be loaned, and creditors will have to reduce the interest rates required to stimulate interest in new credit operations in the market. In other words, the interest rate also follows the logic of prices. The surplus between the average return on investment in companies and the average interest on loans is necessary to keep the credit system functional, in the same way that it is necessary to make a profit on the sale of a product to ensure its continued supply.

This logic does not necessarily hold true at all times. Just as imbalances between supply and demand can cause periods of significant highs or lows in prices, seasons of poor business results due to unpredictable factors can frustrate entrepreneurs’ expectations and leave creditors in a better position. However, in the long term, it is unsustainable for the profitability of credit investments to remain higher than the profitability of businesses, as this would mean that entrepreneurs, who are truly responsible for creating real economic value, would accept receiving less than chronically passive rentiers, even when faced with the possibility of simply ceasing to lead businesses and becoming just another creditor.

A brief addendum is that the average interest rate on loans to companies is always higher than the CDI, which is in force in very short-term credit operations between banks, which have very low risk. Therefore, it is expected that the average return on businesses in general will be considerably above the CDI over long periods.

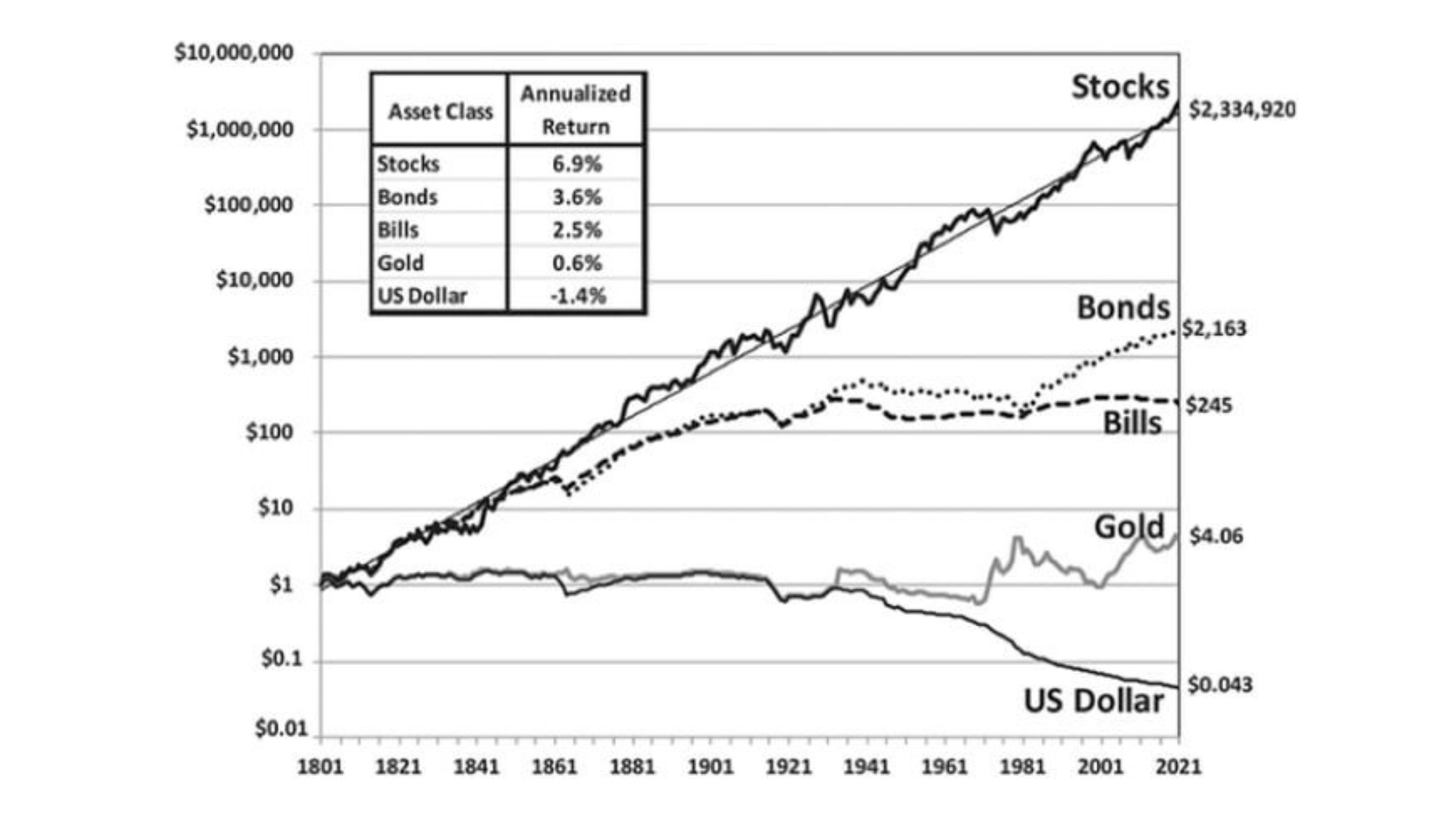

If the theoretical argument is not enough, the most comprehensive empirical data comes from the very long-term study done by Jeremy Siegel, who analyzed fixed income and equity returns in the American market over more than 200 years and summarized the results in this famous graph, originally published in his book “Stocks for the long run”.

Note: real returns, above inflation

There is also anecdotal evidence: have you ever heard of large fortunes created through investments in CDB, LCI, LCA and the like?

When is it time to buy?

Despite the conclusion that being a partner in companies tends to be more profitable than being a creditor in the long term, the equity market is notably cyclical and the purchase price of shares greatly impacts the return obtained. The best way to be sure about the purchase price that is attractive for investments is a well-known process: i) qualitatively analyze how the business of the company in question works; ii) estimate the cash flow generated by the business in the coming years; iii) calculate the intrinsic value of the share by discounting the estimated cash flow at your target rate of return; and iv) only buy when the price is considerably below your estimated intrinsic value (the good old safety margin). It is not a highly complex task, but it does require a certain amount of time. However, there are simple and quick ways to check if there are signs that it may be a good time to look for undervalued shares.

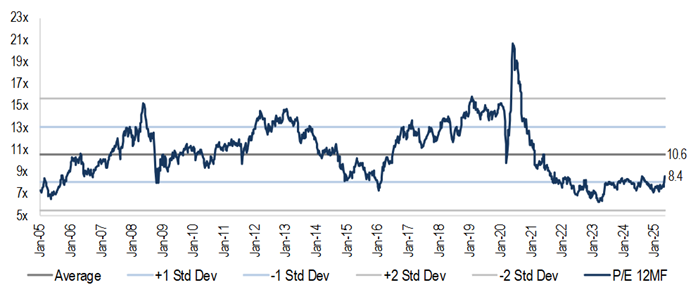

One of these ways is to monitor the evolution of the stock market’s average valuation multiples. Although simplistic, the indicator provides a general idea of how current prices compare to their “normality”. Several investment banks regularly publish this index, which is currently ~21% below its average over the last 20 years.

Average Price/Earnings Multiple* on the Brazilian stock exchange

*Considers estimated profit for the next 12 months Source: BTG Pactual – Brazil Strategy Monitor, May 23rd 2025

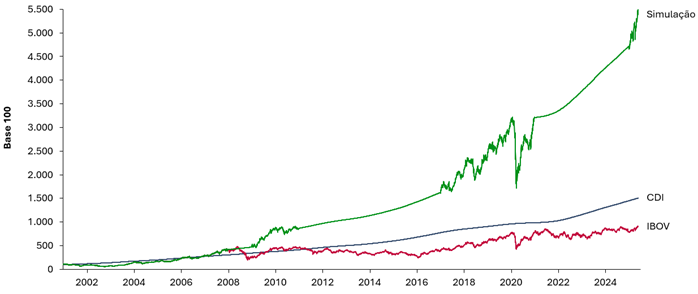

Another way is the one we mentioned at the beginning: check the level of allocation of national stock exchange funds, because when it is low, it is usually a good time to buy. This statement is not immediately obvious, because most of the capital invested in the Brazilian fund industry comes from professional investors and it is implicit that they would be making mistakes along with the other categories (foreign investors and individuals). To test whether this statement is true, let's simulate the return of a simple strategy: invest in IBOV when the level of allocation of national stock exchange funds is at minimum levels (and starts to rise) and in CDI when it is at maximum levels (and starts to fall). The investment periods in each index and the returns obtained in this simulated strategy are illustrated below.

Investment in IBOV and CDI according to local fund allocations in variable income

Simulated strategy return

The interpretation of these facts that seems most fair to us is that local investors, like all others, have pro-cyclical behavior: as the stock market generates good returns, they gain confidence and increase their allocation to the stock market; when stocks start to fall, they become frustrated and migrate to fixed income. This is how the pendulum behavior of the markets is generated, which, despite being a well-known phenomenon, inevitably continues to repeat itself.

The trap is largely psychological. Most people, whether professionals or not, are insecure when faced with uncertainty and seek reassurance in the behavior of those around them. This is a good strategy in many situations in life. If you see a crowd running, it is advisable to run in the same direction and only then ask why. In investments, it is advisable to develop your own analyses and draw your own conclusions regardless of what the majority thinks. The conviction to act in the opposite direction comes from diligent analytical work and a pinch of faith in the old Latin proverb: fortis fortuna adiuvat – fortune favors the brave!

Check out the comments from Ivan Barboza, manager of Ártica Long Term FIA, about this month's letter in YouTube or in Spotify.