How We Find Good Opportunities

Dear investors,

There's a tendency to believe that extraordinary results come from extraordinarily complex methods. This is true in some cases, but it's far from a general rule. There are several activities in which effective methods are simple and well-known. But then, why doesn't everyone do what they know works and achieve excellent results? For at least two reasons. The most obvious is that not everything that's easy to understand is easy to execute. Placing a stone on top of a mountain is simple, in concept. You just have to carry it there. The other, more curious reason is that many simply don't believe something so simple can work and don't even try or don't maintain the discipline of execution, especially necessary in activities where results depend on consistency and take time to appear. Instead of doing the obvious, they continually search for the "magic formula." As you can imagine, investing in stocks is one of these activities.

The investment philosophy we follow, called value investing, is so old, simple, and well-known that it has become commonplace. Many investors claim to follow it and advocate similar concepts, but most of them experience mediocre returns. It feels like something is missing.

Value investing isn't incomplete per se, but it often lacks clarity on how to apply its principles to concrete cases encountered in real life, which resist fitting neatly into generic and abstract definitions. To address this, investors often create their own typologies of investment theses, including more concrete and easily recognizable characteristics that help filter out opportunities of interest and quickly interpret those that resemble predefined schematics.

We also use this tool to create mental models to guide our search for good opportunities and categorize our investments. Below, we'll briefly review the principles that underpin our main thesis models and explain each of them.

Traditional Principles

What we seek are opportunities to buy good, affordable companies. Failing to find them, we start looking for good companies at a fair price or acceptable companies at deeply discounted prices. The method is the same when buying anything, and the difficulty lies in properly evaluating the target and the offered price. Therefore, the first step is to understand what constitutes a good company.

If our primary objective is to obtain the highest possible return on invested capital, we must seek companies capable of achieving precisely that: obtaining high profitability on the capital employed in their operations. This is no easy task due to the dynamics of the free market itself, in which several companies compete with each other to be chosen by their potential customers, who seek the best possible product or service at the price they are willing to pay. This auction of offers puts pressure on the selling prices charged by the business and, under normal conditions, causes the profitability of capital invested in its operations to converge towards the average cost of capital in the market, composed of the basic interest rate plus a return premium that compensates for the business risk, in the view of investors in general.

If our primary objective is to obtain the highest possible return on invested capital, we must seek companies capable of achieving precisely that: obtaining high profitability on the capital employed in their operations. This is no easy task due to the dynamics of the free market itself, in which several companies compete with each other to be chosen by their potential customers, who seek the best possible product or service at the price they are willing to pay. This auction of offers puts pressure on the selling prices charged by the business and, under normal conditions, causes the profitability of capital invested in its operations to converge towards the average cost of capital in the market, composed of the basic interest rate plus a return premium that compensates for the business risk, in the view of investors in general.

There are several other possible advantages, but this is a long topic and we'll leave it for another occasion. For now, the only interest is understanding that good companies are those with sustainable competitive advantages and consistently generate returns on investments in their operations that are higher than the average market cost of capital. The next point is to understand what it means to say a company is cheap.

The shareholders' capital effectively employed in a company's operations is, roughly speaking, the value of equity recorded in its financial statements. To obtain the business's intrinsic rate of return, it would be necessary to purchase shares at a price close to their book value. This is rarely possible, as share prices are set in the market by auction. When it is common knowledge that a business generates high and consistent returns, investors compete to buy its shares, driving prices far beyond book value, to a level where the implicit return on investment once again approaches the average cost of capital.

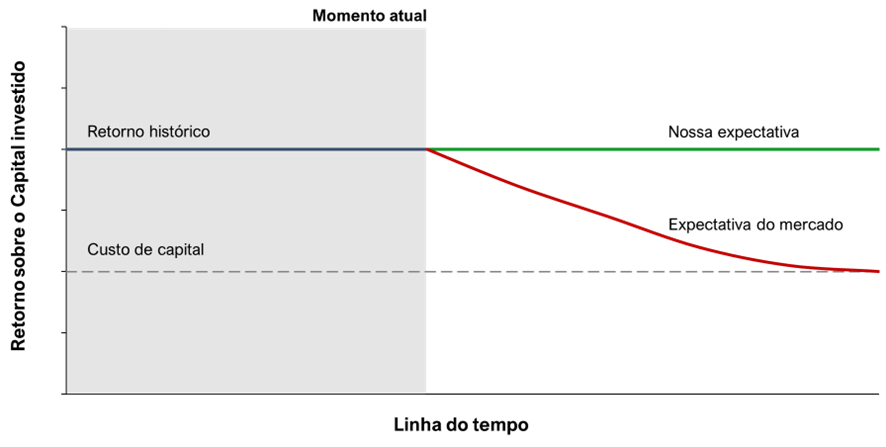

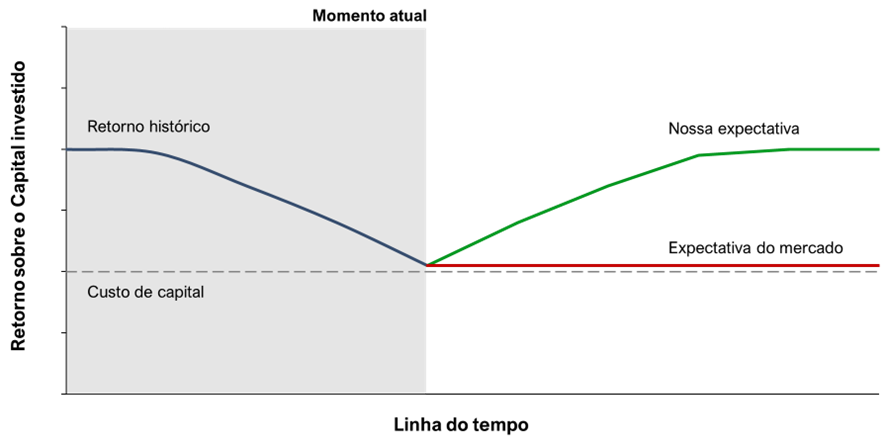

If the general public of investors were always efficient in evaluating investment opportunities, all prices should always converge to values that would result in the same median returns. This is not actually the case, but we can affirm that stock prices always reflect the market's average expectation for the company's future cash flow, discounted to present value using the average cost of capital as the discount rate. Thus, when we state that a stock is cheap, we are saying that our expectations for its future results are higher than the market's expectations. It is important to be clear on this point and to understand why we are projecting performance above what other investors believe. Our mental models for finding good opportunities were defined precisely from the perspective of identifying in which situations we might be interested in going against the general market belief.

Ultrarunners

Ideal companies are those that consistently generate good results. The only problem is that, given a long history of good and stable results, forecasting the coming years is an easy task for any investor, and the market usually prices shares accordingly, eliminating atypical return premiums.

Shares of such companies tend to fall only when people become generally pessimistic. Macroeconomic or political problems in the country, for example, can cause a segment of the market to believe that all businesses will suffer and adjust their expectations accordingly. If the shares of good companies fall along with the others, attractive opportunities may arise.

Buying stocks in these dire economic scenarios means believing in the business's continued existence even amidst adversity. For this thesis to be valid, the company must have clear and relevant competitive advantages capable of protecting the business throughout the crisis or, at least, enabling it to survive until good times return.

Schematically, the graph below illustrates the difference between our expectations and those implicit in the market price in this type of thesis.

Examples of our investments that fit into this category are Fleury and Caixa Seguridade, companies with excellent and consistent results that we had the opportunity to acquire at attractive prices due to factors external to their businesses.

Challengers

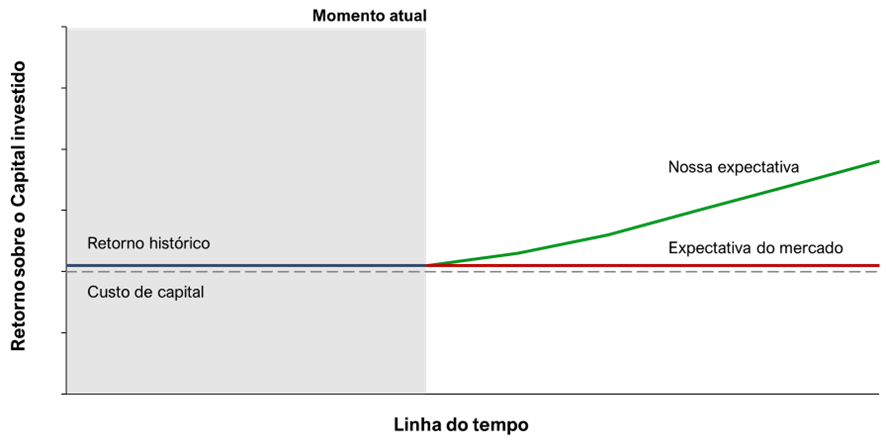

Another type of situation is when a company without a distinguished track record undergoes a change that could boost its profitability. This could be something internal, such as the launch of a promising product or entry into a new business segment, or something completely unrelated to the company itself, such as a price increase due to a sudden increase in demand.

Opportunities like these are difficult to spot because they require in-depth analysis of businesses with less-than-impressive track records. Something needs to catch our attention for us to dedicate time to the company. Sometimes it's reports from industry insiders about changes taking place. Sometimes we stumble upon an interesting idea while we're studying other things.

The upside of finding opportunities like this is that, because they're less visible, the potential increase in profitability may be completely overlooked in the market's assessment. If we can buy at a price that still yields an acceptable return if we're wrong about the move, there's a clear asymmetry between potential return and risk. It's as if we're buying a free option to participate in the potentially optimistic future for the business.

A famous example is Nvidia, which manufactured video cards for electronic games and realized its technology could be used for the computational processing required by artificial intelligence models. Entering this new segment dramatically increased the company's revenue and profitability. Unfortunately, we didn't participate in this thesis, but a more modest example is our investment in Marcopolo, a leader in the bus body sector in Brazil. The company experienced a decade of weak sales, but the Brazilian bus fleet was aging, generating pent-up demand that began to manifest itself in 2023, when there was no longer sufficient manufacturing capacity in the country. With this imbalance between supply and demand, Marcopolo's profitability doubled and its share price tripled. For those interested, we shared this thesis in our October 2021 letter.

Sprinters

There remains the most traditional category of opportunities among value investors: businesses that are simply too cheap, regardless of their quality. Companies that are unappreciated by the market may go through a difficult period and have their shares excessively penalized. They may be completely disregarded by most investors, due to low liquidity or the mediocrity of their business, and their shares may fluctuate erratically, depending more on the decisions of one investor or another than on efficient market auction dynamics.

Regardless of the reason for the low price, the essence of these theories is to buy so cheaply that the risk of loss is low. Sometimes, opportunities arise to buy below the liquidation price of the business. In other words, if the company were to close its doors, sell all its assets, and pay off its liabilities, it would have more capital remaining than all its shares are worth on the stock market.

For these theses to be truly successful, the stock price must correct within a few years. The longer the time, the closer the return on investment will be to the business's natural profitability, which, in these cases, is lower than we desire. Because time is against the investor in these situations, it's not our preferred investment. Typically, we'll only buy stocks with this profile if we can see some trigger that makes a repricing likely in the near future.

What has made this category so well-known, and what keeps it in our mental models, is the fact that there are always opportunities like this somewhere in the market. Finding them depends solely on persistence and the amount of time invested in searching.

Our investment in the English company Anexo falls into this category and exemplifies the search process well. We conducted a quantitative mapping process in search of companies valued at very low multiples but with a track record of acceptable profitability, which generated a list of just over 300 stocks. After an initial manual screening—a quick look at each company's profile—around 25 companies remained. A second, more cautious screening resulted in five remaining. Anexo was among the finalists.

Most often, there won't be any good opportunities even among hundreds of companies mapped this way, but the protocol can be repeated several times, with different filtering criteria, until something is found.

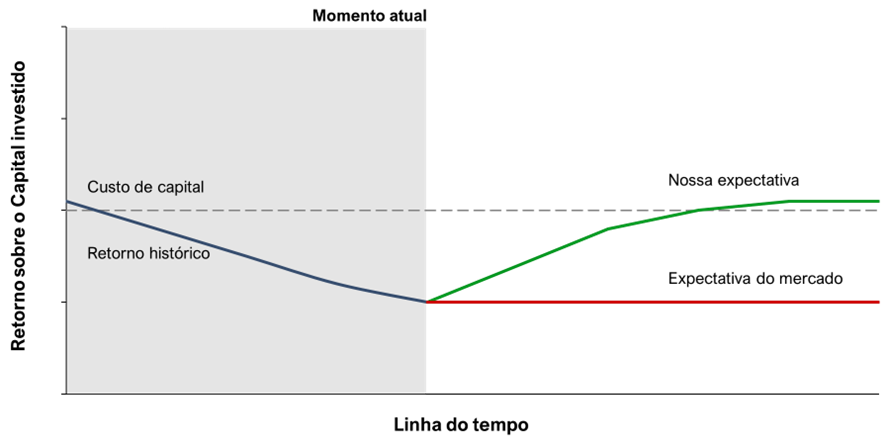

Comeback players

Finally, our favorite type of opportunity. Even excellent companies have their bad luck and occasionally post poor results. The market is skittish and short-term. When a streak of consistent profits is broken and disappoints analysts' expectations, shares fall. Despite a company's track record of success, many investors may be wary that recent results signal a new level of profitability, or they may sell because they're unwilling to endure a few quarters of weak results. When this happens, it's worth investigating. Outside of major economic crises, it's rare to have the opportunity to pay low for high-quality stocks.

In these cases, the core of the investment thesis is understanding whether the negative event responsible for the poor results represents systemic changes in the business, which may be irreversible, or whether the effect is temporary. The worrisome systemic changes are those that eliminate competitive advantages associated with a history of above-average returns. If this is the case for the company being evaluated, the price drop may be well justified, as it is unlikely to regain its original position. An example of a lost competitive advantage is the story of Intel, which dominated the CPU (computer processor) market for decades, until its technology was surpassed by the partnership between AMD and TSCM in 2017. In recent years, Intel went from $20 billion in annual profit to $20 billion in losses and is still unable to produce CPUs as advanced as its competitors.

When bad results are temporary, the opportunity is obviously good, but caution is needed before jumping to that conclusion. High-quality companies are often well covered by the market. When their stock price falls in a favorable economic environment, it means that most investors believe that, due to factors specifically related to the business, the downturn is not temporary or that the downturn may last for a long time. The majority opinion may be wrong, but we take special care to be especially diligent before going against the market on theses under everyone's scrutiny.

Our investment in Porto, a leader in the auto insurance sector and now present in several other segments, represents this category well. Its profitability was negatively impacted by shocks the auto insurance sector suffered during the pandemic. In short, for a period, insurance policies were sold at low prices, based on assumptions that later proved to be optimistic. When costs rose above forecasts, Porto's profits fell, and the market penalized its shares. However, we saw new policy prices adjusted and Porto maintained its customer base intact, so it was only a matter of time before the low-priced policies expired and were renewed at the adjusted prices. The recovery path has not had any negative surprises, and the investment has already been successful. For those seeking more details, we explained this thesis in the March 2024 letter.

Closing

Other investors have already shared how they classify their theses, and there seems to be a good deal of personal preference in defining these categories. The range of opportunities covered tends to overlap widely, but the way they are grouped and the nuances in the descriptions vary from case to case. Still, reading about these examples from the past has helped us understand the opportunity selection process and develop our own mental models. In honor of the generosity of those who came before us, we also offer our contribution to this topic.