Investment Case: Unipar Carbocloro

Dear investors,

We've had a few months of very turbulent markets. Given the period of uncertainty and anxiety, we've dedicated our latest letters to aspects more appropriate for that moment, such as investing in times of crisis and the historical returns of stocks vs. fixed income in various countries (including Brazil). For those who haven't read them yet, all of these letters are published on our website.

This month, we decided to share our investment case in Unipar Carbocloro.

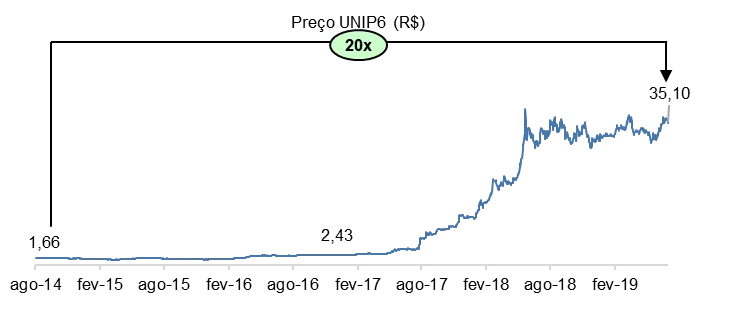

Unipar represented Arcádia's largest position in the 2015-19 period, and was our first 20-bagger (it provided a return equal to 20x the invested capital!), as detailed in the chart below.

Chart 1 – Historical return of UNIP61

Below, we detail our investment process in the company, from identifying the opportunity, through the purchase decision, and, most recently, the sale decision. Currently, we no longer hold the company in the fund.

Founded in 1969, Unipar Carbocloro is a petrochemical company. Currently, the company focuses on three segments: chlorine, soda (the largest producer in Latin America), and PVC (the second-largest producer).

For those who remember their high school chemistry classes, Unipar's production process is clear. The company uses salt (NaCl), water (H2O), and electricity as its main raw materials, transforming them into chlorine (Cl2) and caustic soda (NaOH).

Chlorine has a variety of industrial applications, including PVC production (plumbing pipe manufacturing), water and sewage treatment, agricultural pesticides, pulp and paper, and others. Chlorine can also be used to produce explosives, which gives the product two characteristics that make Unipar's business attractive: (1) due to the risk of explosion, chlorine cannot be transported over long distances, and (2) because of this application, a multitude of licenses are required for a company to be authorized to produce chlorine (and consequently, lye)—significant barriers to entry.

These characteristics give the industry a natural monopoly and make it a highly profitable business. Unipar has plants in the cities of Santo André (SP) and Cubatão (SP), allowing it to serve the South and Southeast regions, home to the country's largest consumers.

Since soda and chlorine are typically produced together, the soda market also faces the same barriers to entry. The main difference is that, because soda is non-explosive, it can be transported over long distances. Therefore, the company also faces global competition, and Unipar's prices are in line with those of the global market.

Focusing on these three segments is a recent development for the company. Historically, the company operated as a holding company with stakes in companies operating in various petrochemical sectors and even held a stake in a wind turbine manufacturer (Tecsis), currently based in Rio de Janeiro. The table below illustrates the corporate structure that comprised Unipar in 2006:

Chart 2 – Unipar’s organizational structure in 2006

Between 2006 and 2010, a series of transactions were carried out to simplify the company's corporate structure and focus on its most profitable business (Carbocloro). These transactions included the sale of Petroflex (2007); the sale of União Terminais (sold to Grupo Ultra in 2008); and Quattor (a company that encompassed Unipar's stake in Petroquímica União, Rio Polímeros, Polietilenos União), Polibutenos, and Unipar Comercial (sold to Braskem in 2010).

The complex history of corporate restructuring made analysis difficult and made the company potentially misunderstood by the market.

In 2013, Unipar acquired the remaining 50% in Carbocloro (until then, its stake was 50%) and became a company whose only asset was Carbocloro – a structure similar to the one that exists today.2

This transaction caught our attention because the terms of the deal presented a significant disparity when compared to Unipar's own market value. Unipar's main asset at the time was a 50% stake in Carbocloro, and the offer to purchase the remaining 50% was 20-30% higher than Unipar's market value! Since the two halves of the same asset should obviously have the same value, the offer made it clear that Unipar executives believed their operations were significantly undervalued on the stock market.

We then decided to deepen our analysis.

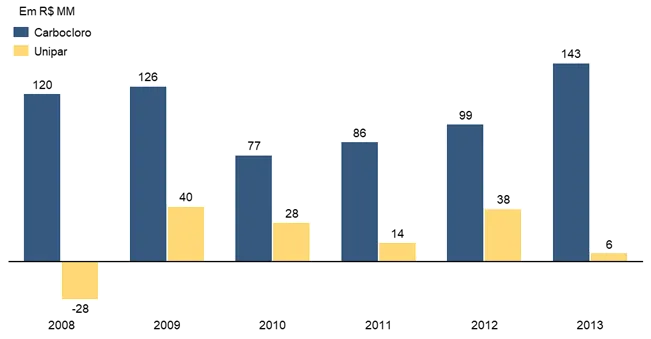

It made little sense to evaluate the financial history of the holding company Unipar, as it contained several operations that were sold during the restructuring, so the accounting results did not reflect the business's future outlook. As shown in the chart below, an analysis that captured only Unipar's results (and not Carbocloro's) would be ineffective in analyzing the company.

Chart 3 – Historical normalized net income (Unipar x Carbocloro)

The key was to analyze Carbocloro. Since Unipar provided little information about Carbocloro, we sought historical operational and financial information from alternative sources, such as balance sheets published in the Official Gazette. We recovered information dating back to the 1980s!

The findings were quite encouraging, as they showed typical characteristics of good businesses: stable volumes, high margins, and high cash conversion, typical of businesses with few competitors and a high barrier to entry.

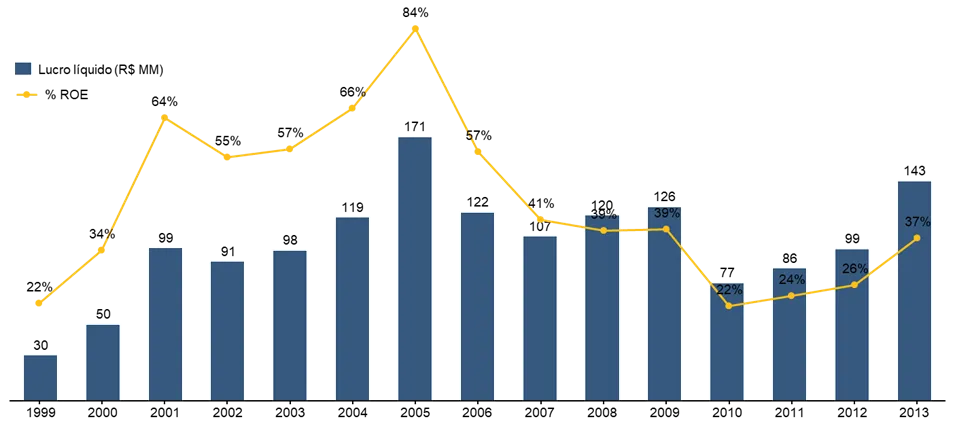

The chart below shows Carbocloro's net income and return on equity (ROE) at the time of the analysis. It should be noted that the company had never posted a loss, even during the worst crises, such as 2002-2003.

Chart 4 – Carbocloro’s historical net income and ROE

One negative point for the company was its lack of growth: its net income had not shown significant growth since 2001. We understood that two factors were weighing against the company: (1) the industry's idle capacity was near all-time highs, closely linked to the onset of the crisis during Dilma's administration; (2) soda prices were low on the international market, which, combined with a depreciated dollar, contributed to lower-than-normal profits. This conclusion, in a way, was comforting, because even during a downturn in the cycle, the company remained profitable and a cash generator.

Regarding valuation, our estimates at the time were that, under conservative scenarios, the company seemed quite discounted. Based on its cash generation, we estimated the company should be worth at least double its current stock market valuation—even with the CDI at the time hovering around 12%!

After considering everything, we made the decision to invest, starting purchases at the end of 2014.

Despite the stock's high return, we had to be very patient and disciplined. This is because we started buying in August 2014, and in just over six months, the shares had fallen approximately 25% (compared to a 12% drop in the Ibovespa index during the period)! Without a doubt, this wasn't an encouraging start for the position.

A drop of this magnitude justified a detailed review of the investment to assess whether we had made any mistakes or whether there had been significant changes in the company or the market that justified such a drop in value.

We found that, in fact, the company's operating results continued to be even better than our expectations, so the drop in shares seemed to be driven solely by market fear that macro factors could contaminate the company's results (the timing coincided with the peak of the crisis that culminated in the impeachment in 2016).

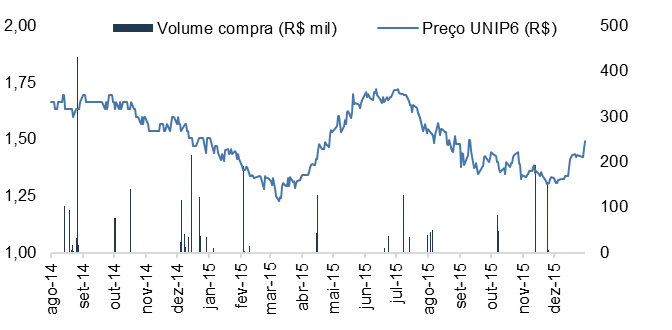

Our conclusion was that the drop seemed unreasonable, and we seized it as an opportunity to continue buying at an even lower price. We built the position over an 18-month period, during which the price remained attractive, as shown in the chart below.

Chart 5 – UNIP6 share price3 compared to the purchase volume

In this same period, the company's controller, aware of the discounted share price, made a purchase offer to close the capital at R$ 1.79/share4 (a premium of 15% over the then-current price). Fortunately, we were able to coordinate with other minority shareholders and veto the purchase proposal at this price.

Starting in 2016, the stock began to deliver good returns. Three factors contributed to the improvement in results and, consequently, the share price.

The first was the company's own performance, which, benefiting from the strong dollar exchange rate, generated cash of nearly R$1,000,000 over a three-year period (2014-16)—a figure higher than the market value at the time of our investment and higher than our estimated for the period. This cash generation was used to reduce net debt (which fell from R$1,000,000 to R$1,880,000 over the period), with the remainder paid to shareholders in the form of dividends.

The second factor was the company's 2016 acquisition of Solvay Indupa, a competitor with operations in Brazil and Argentina and a presence in the soda, chlorine, and PVC segments. Solvay Indupa had been up for sale for several years, and taking advantage of the lack of buyers (a sale to Braskem in 2014 was blocked by antitrust authorities), Unipar was able to acquire the asset at a favorable price. After a well-executed turnaround, Indupa became a cash-generating unit and enabled a significant increase in Unipar's results.

The third factor that influenced Unipar's results was the increase in the price of soda on the international market, as can be seen in the chart below. This increase was largely due to environmental issues, which prohibited the production of chlorine and soda using an outdated technology and forced several factories around the world to halt production. Europe was the first region to impose this restriction, in 2017, which eliminated a significant portion of global supply and drove up commodity prices. Other factors also contributed, such as growing demand from China and the fact that chlorine and soda plants in the United States were already operating close to their production capacity.

Chart 6 – Historical price of caustic soda (white line)

It is important to highlight that Unipar itself will have to replace its mercury plant in the coming years, which will require a significant investment.

Due to these factors, between 2015 and 2018, the company increased its net profit sixfold and its stock appreciated 20fold. In early 2019, due to the strong appreciation of the stock and the rise in the price of soda, we decided to sell our Unipar shares to invest in other businesses with greater appreciation potential.

We are still closely monitoring the stock, waiting for the day when a new buying opportunity at attractive prices will arise.

1 UNIP6 prices shown in the charts are adjusted for dividends and stock splits.

2 For the sake of completeness, there were two other transactions not mentioned. The first was the acquisition of a 25.25% stake in Tecsis (a wind turbine blade manufacturer) in 2011, and the second was the purchase of Indupa in 2016 (detailed in the text).

3 UNIP6 prices shown in the charts are adjusted for dividends and stock splits.

4 The original takeover price was R$4.40/UNIP6 share; the price presented in the text was adjusted considering dividends and stock splits.