Americanas and SUR: risk or noise?

Dear investors,

One of the proverbs often repeated by Charlie Munger, the Berkshire Hathaway partner who turned 99 this month, is that "to a man with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail." In his always laconic style, it's a critique of the tendency to see the world in an oversimplified way, trying to explain everything through narrow ideas, rather than seeking to understand the nuances and complexities of each situation.

With all the turmoil Brazil has been experiencing, investors have been closely following every development, no matter how minor, regarding the economy and politics. We were no exception. We've dedicated more time than usual to these topics in recent months. However, we feel like newspaper headlines have been given more weight than they should in Brazilian investors' decisions. News has been the market's "hammer," considered a relevant factor in estimates about the likely future of the economy, even when highly speculative or with a very limited impact.

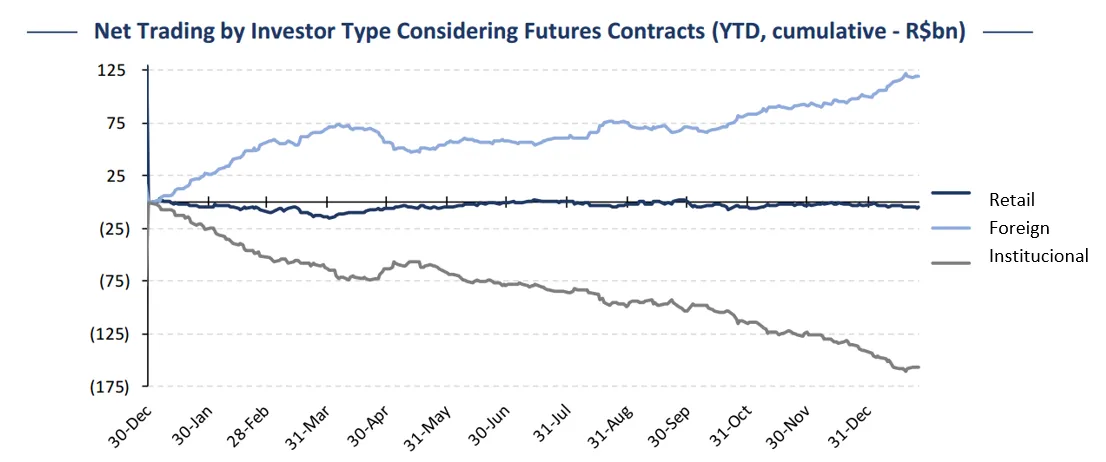

Meanwhile, foreign investors have purchased approximately R$120 billion worth of shares on the Brazilian stock exchange in the last 12 months, which were then sold by local investors. In other words, foreigners are "betting" that the future of our economy will be better than Brazilians themselves believe. Only one side can be correct.

Source: BTG (Brazil: Follow the Money)

There's an important detail: the sales by Brazilian institutional investors weren't solely driven by their managers' opinions. Equity and multimarket funds suffered R$146 billion in redemptions during this period, forcing managers to sell so they can return the money to their shareholders. Thus, this selling movement reflects the allocation decisions of the end user group of Brazilian investors, who are especially susceptible to the "man with a hammer" syndrome because they spend far less time than professional investors delving into in-depth economic analyses.

To illustrate how some recent events may have had a greater impact than warranted, let's discuss two cases that have gained attention in the last month: the Lojas Americanas bankruptcy and the new government's announcement of its intention to create a common currency with Argentina, the SUR.

The Americanas gap

Every now and then, a major fraud case is revealed in the markets. In 2020, it was IRB Brasil. This month, it was Americanas, which, apparently so far, failed to account for R$20 billion in debt on its balance sheets. The case has garnered so much media attention that several articles have explained what happened and speculated about the company's possible future, so we'll assume some prior knowledge and simply share our thoughts.

The value of the hidden debts is so great that the company has no chance of salvation without an injection of new capital. However, from a purely pragmatic point of view, the situation is tragic for Americanas shareholders, who saw their investments in the company reduced to dust overnight; bad for the company's creditors and suppliers, who will not receive everything they are owed; indifferent to the majority of the market, which had no relationship with Americanas; and good for competing retailers, who will be able to take a good part of the market share previously occupied by Americanas.

The largest group among these four is the indifferent or little affected. The loss was enormous for the company, which was worth R$10 billion on the stock exchange, but not so significant for the stock market itself, whose combined listed companies are now worth around R$4.2 trillion. However, the issue gained such prominence in the markets that it increased the overall cost of private credit operations.

Banks and credit fund managers suddenly became more aware of this type of risk (which has always existed) and began to overestimate its relevance when calculating appropriate interest rates for each loan. A completely different episode illustrates this overreaction to a newly materialized risk.

On September 11, 2001, two planes were hijacked by terrorists and flown into the World Trade Center (the Twin Towers) in the United States. Afterward, the number of airline passengers in the United States suddenly dropped by more than 30% compared to the number of passengers in the previous months. With the memory of the terrorist attack fresh in their minds, fear of flying increased, and countless people decided to replace airplane travel with car travel—a decision quite understandable and intuitive to human psychology, but completely irrational. The risk of death from air travel is much lower than the risk of death from road travel (currently about 18 times lower for commercial aircraft). Thus, the decision to travel by car, fueled by the recent memory of the attack, killed thousands upon thousands of people around the world. A tragedy much quieter than that of the people in the buildings under attack, but just as lethal.

In our last letter, we discussed the difficulties of maintaining rationality even when it points in a direction different from what's intuitive. It would certainly be uncomfortable to take a flight with photos of the plane crashes involved in the terrorist attack on every newspaper cover, but it would still be the rational decision. One of the most important skills for an investor to cultivate is to act according to what makes sense, rather than the most psychologically comfortable way.

One final comment about Americanas before we move on: to avoid investing in the company, it wasn't necessary to detect fraud, something very difficult to do from an outside perspective. It was enough to note that it had suffered nine years of losses in the last 10 years and depended on several consecutive capital injections to remain solvent. These are not the hallmarks of a good business.

The reverie about SUR

On his first diplomatic trip to Argentina, the new president announced the possible creation of a common currency to facilitate trade transactions in Latin America, with the suggested name of SUR. The episode caused some initial uproar, but it resonated much less in the market than the Americanas case. We believe that, based on the consensus of several experts, the plan is unlikely to come to fruition. In our own analysis of how such a project could evolve, we sought to understand the stage Mercosur was at compared to the history of the European Union.

In 1957, the European Economic Community (EEC) emerged, the economic bloc that preceded the European Union and established free trade and labor movement among the signatory countries. Thirteen years later (1970), a group was created to develop a plan to unify the member countries' currencies, but its implementation was initially thwarted by the complexity of aligning multiple currencies amid exchange rate instability. Only nine years later (1979) did the European Currency Unit (ECU) emerge, a scriptural currency used for financial transactions between the countries of the economic bloc. The ECU evolved into the Euro 20 years later (1999), and the adoption of the Euro as a currency took another three years (2002).

If we compare the recent announcement of the intention to evaluate the creation of the SUR with the creation of the European study group that emerged in 1970 and follow the same timeline from that point, the Sur would be born in 2032 as something similar to the ECU and would become a common currency in circulation in 2055. Even if there is good political will now, there are so many complexities and obstacles that something like this is unlikely to be implemented in a single presidential term, so it would require the support of consecutive governments in both countries for it to ever come to fruition. It may never happen.

This brief history alone is enough to allay concerns about the potential short-term impacts this project could have. Considering the barrage of criticism the idea has received, it's possible the new administration won't even want to expend political capital pursuing this issue.

The world likes new things

The risk of following these economic and political events too closely is that we gradually lose sight of the bigger picture. In our eagerness to consider each new development, we begin to forget the structural factors that develop slowly but have a greater impact.

In the letter we published in November, we discussed the positive impact that the trend toward decentralizing production chains, currently heavily dependent on Asian countries, could have on Brazil's economic development. In the same vein, the plan to decarbonize the economy could make Brazil's energy matrix, much cleaner than average, an attractive source of new investments in our country. These factors will remain valid for several years, but they tend to be forgotten by the general public, giving way to new developments, however less relevant they may be compared to the old news.

Although news impacts stock prices in the short term, long-term price movements are much more closely correlated with each company's financial results. Therefore, a constant effort is required to remain cool-headed and skeptical about current issues, separating what can truly have a lasting impact from what is merely noise. This is especially true when it comes to political issues, where noise levels are high.

What do buyers see?

Looking at the Brazilian scenario from afar, with a broader perspective and less attention to every political storm, our dramas are part of the country's normality: Brazil is constantly experiencing controversies and scandals. The specifics of the current drama are of little relevance in the long-term outlook. Brazil will most likely continue with the low economic growth it has experienced in recent decades, the result of confusing legislation, enormous productivity challenges, and an inefficient government.

Although not a very encouraging forecast, this baseline scenario is already reflected in average local market price levels. This is why real interest rates are higher and company valuation multiples in Brazil are lower than in developed economies. What motivates investors buying now, foreign or otherwise, is certainly the current price level, well below averages that already take into account our consistently tepid economy. It's a discounted price that offsets a good deal of macroeconomic and political risk.

We've already said that prices have been low for several months, and the fact that we haven't yet seen a reversal in market trends may bother the most eager traders. Therefore, it's always worth emphasizing that the timing of a reversal is unpredictable and could take several months. We always invest with the long term in mind, not because we like to make money slowly, but because we believe it's the safest and most assertive approach possible.