30 years of crises in Brazil

Dear investors,

Political and economic crises are a normal part of the Brazilian stock market. Because half of our capital flows come from foreign investors, we import all global crises and even contribute a few more domestic crises.

Since the Plano Real, we've had ten periods in which the Bovespa index fell at least 25% from its peak in the previous six months. We used this criterion to select the major crises within this timeframe and will briefly summarize each of them. By observing how the stock market performed during these crises and in the years that followed, we'll seek to understand the best way to manage investments in the turbulent Brazilian market.

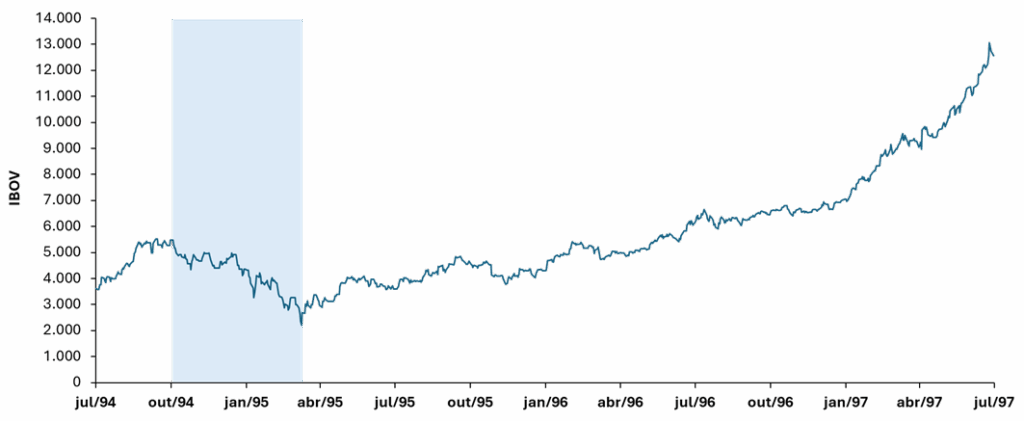

1995: Mexican Crisis (Tequila Effect)

In December 1994, after a period of political instability and significant fiscal deficits, Mexico experienced an abrupt devaluation of its currency, the peso, which rose from 3.5 to over 7 pesos per dollar in just a few days. In the following months, the country experienced massive foreign capital flight, high inflation, and recession.

The event created widespread distrust of all emerging markets. Brazil had recently implemented the Real Plan, and fears arose that the real would follow the same path as the Mexican peso. To stem capital flight, the Brazilian Central Bank drastically raised interest rates in early 1995, and the stock market suffered, falling 60% from its recent high.

The measures proved effective in containing the damage caused by the crisis and maintaining monetary stability. The following years were excellent for the Brazilian stock market. The IBOV index grew fivefold before being hit by a new crisis originating in Asia.

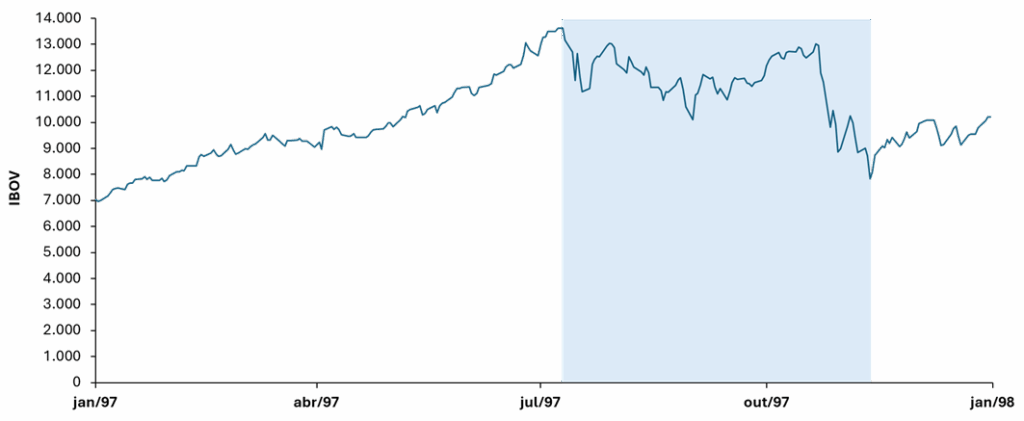

1997: Asian Crisis

The 1990s marked the end of the economic miracle period for several Southeast Asian countries. The economic model that transformed the region was based on bringing in foreign capital to finance the development of export industries that took advantage of the abundant cheap labor available. The policy was successful for decades. As an example, South Korea's per capita GDP rose from 1960 to 1997. However, very positive economic cycles often lead to excesses, and this was also the outcome of Asian economic miracles.

The availability of easy foreign currency credit led Southeast Asian governments to borrow to finance all kinds of development projects in their countries without properly assessing their profitability and risks. When results began to disappoint foreign investors' expectations, credit sources dwindled, and foreign capital flows became negative.

The crisis was triggered by the devaluation of the baht, Thailand's currency. Until July 1997, Thailand adopted a fixed exchange rate regime that kept the baht stable against the dollar. This regime encouraged many Thai companies and banks to take out dollar-denominated loans with the plan to repay them with their baht revenues, disregarding the exchange rate risk involved. When foreign capital began to leave the country, it was no longer possible to maintain the exchange rate peg, and the baht collapsed. The consequence was a wave of insolvencies that brought the Thai economy to the brink of collapse. The crisis first spread to other countries in the region and then to markets around the world. The Brazilian stock market reached a low of 43% between July and November 1997. In the first months of 1998, the market recovered, but another similar crisis soon followed, linked to Russia.

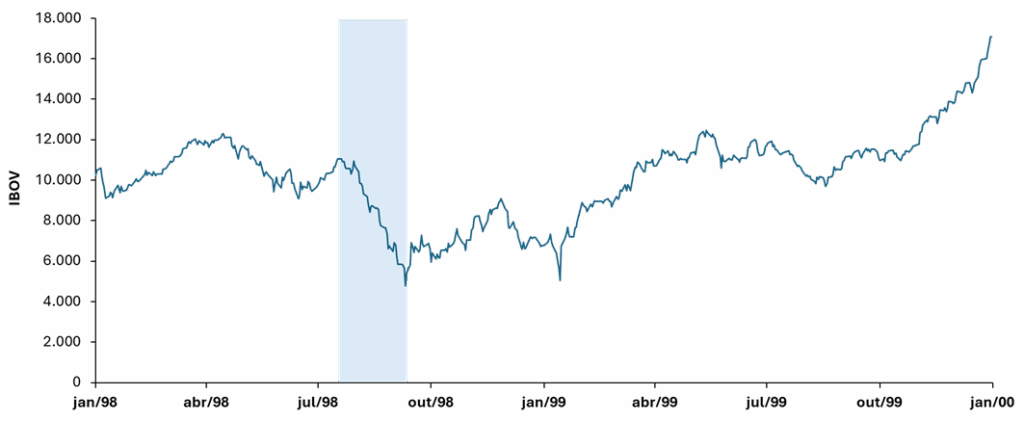

1998: Russian Moratorium

In 1998, post-Soviet Russia was experiencing persistent fiscal deficits, dependence on foreign capital, and mounting public debt when, on August 17, the Russian government announced an emergency plan involving the devaluation of the ruble, the restructuring of the Russian banking system, and a partial moratorium on its domestic debt. The announcement surprised international creditors and triggered an even more intense crisis of confidence that generated even more intense capital outflows from Russia and other emerging markets.

At the time, Brazil adopted a currency band system that kept the real overvalued, and our public debt was partially pegged to the dollar. Given the Russian crisis, investors began to doubt the Brazilian government's ability to maintain the currency band system. There were large outflows of foreign capital, pressure on international currency reserves, and high volatility in the stock market. The IBOV index fell 61% from its year-end high before beginning to recover.

In November 1998, Brazil took out loans from the IMF to protect its exchange rate and avert an impending crisis, but the measure was ineffective. On January 15, 1999, the Central Bank announced the abandonment of the exchange rate band regime, which was replaced by the floating exchange rate regime that remains in effect today. On the date of the announcement, the IBOV rose 33%, and there was a strong recovery in the following months. By the end of March, the IBOV had risen 112% compared to its last price before the announcement.

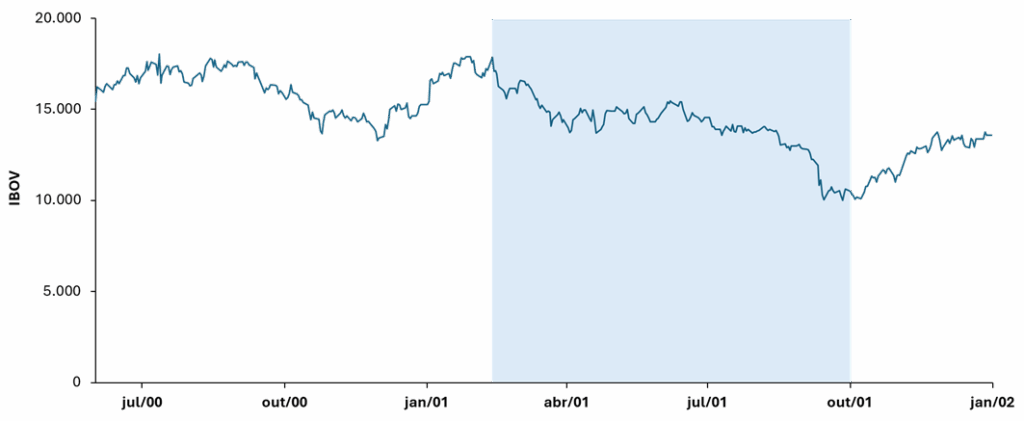

2001: Energy crisis and 9/11 terrorist attack

In 2000, Brazilian GDP grew 4.4%, driven by the industrial sector and exports benefiting from the devaluation of the real following the adoption of the floating exchange rate regime. The following year, an infrastructure bottleneck emerged in the electricity sector. Partly due to scarce rainfall and partly due to a lack of investment in electricity generation in previous years, in 2001 there was insufficient capacity to allow the national industry to continue growing. In May, the government announced the energy rationing plan, the "blackout," which imposed a 20% reduction in consumption, with fines and supply cuts for those who failed to meet the target. Inevitably, economic growth was compromised, and GDP grew only 1.4% that year.

The external environment also contributed to the deterioration of our stock market. Argentina was mired in an economic crisis that also created distrust in Brazil, and in September the terrorist attack that brought down the Twin Towers in New York occurred, sending shockwaves through global markets. The IBOV (Bovespa Stock Exchange) hit its lowest point of the year in the same month, 44% below its January high. In the following months, the markets partially recovered and by the end of December had risen 31% from its lowest point. However, the IBOV would only surpass its last high in October 2003, partly because we experienced another crisis in 2002. This time, it was solely due to the local political climate.

2002: Pre-election crisis (Lula's first term)

When Lula began to lead in the polls during the 2002 elections, investors began to fear a rupture in the Brazilian government's economic policy. The Workers' Party (PT) had a historically aggressive rhetoric that fueled speculation about the possibility of a public debt default, uncontrolled inflation, and state intervention in the economy. The crisis of distrust led to mass redemptions of capital invested in local investment funds, forcing stock sales at any price that sent the IBOV (Bovespa) index down to 39% from its year-end high.

After Lula's inauguration, the government showed signs of continuity that reassured the market: the Central Bank president was retained, the appointment of Antonio Palocci to the Ministry of Finance was well received by the market, and the federal government published a letter committing to surplus targets and inflation control. In the following years, the Brazilian market experienced the longest bull market cycle in recent history, driven by China's growth, which caused a global commodity boom and benefited Brazilian exports. From its low in October 2002 to May 2008, at its peak before the subprime crisis, the IBOV rose 778%.

2008: Subprime

In the 2000s, with low interest rates and a continued upward trend in the American real estate market, financial institutions offering credit for new home purchases began to relax their risk criteria. Assumptions that real estate would always be sufficient collateral, as it would continue to appreciate in value, and that the formation of diversified portfolios would mitigate credit risks, allowed the creation of a massive number of high-risk real estate credit securities, known as subbrime. Rating agencies classified these real estate portfolios as low-risk assets, and the extra returns they offered attracted capital from financial institutions and institutional investors around the world. In the second half of 2006, American real estate prices began to fall.

In 2007, the housing market price decline intensified, and subprime borrowers began to default. Real estate became insufficient collateral, and there was no way to recover the invested capital. In 2008, the crisis erupted. The entire chain of securities assets based on subprime loans began to collapse, contaminating the balance sheets of various types of institutional investors: banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and others.

The crisis peaked in the second half of 2008, when several American financial institutions became insolvent. The landmark event was the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States before the crisis. Soon after, Bear Sterns, the fifth-largest American investment bank, and AIG, the world's largest insurer at the time, had to be rescued from imminent bankruptcy by the Federal Reserve, which feared a collapse of the global financial system if the major institutions were not kept solvent.

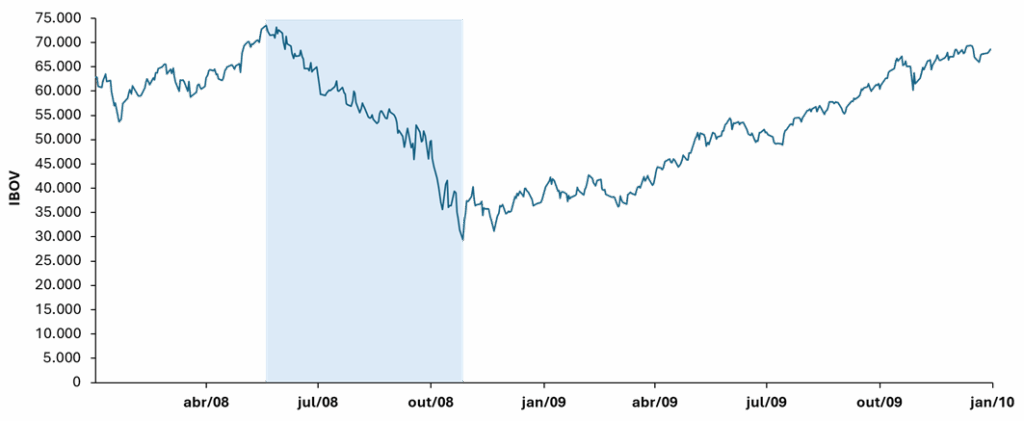

Brazil could not help but be impacted by this grim scenario. Between May and October 2008, the IBOV index fell 60%. Despite the severity of the crisis, the market began to recover relatively quickly. Within a year of its lowest point, the IBOV index rose 115%, but only surpassed its pre-crisis high almost ten years later, in September 2017.

2011: Greek debt crisis

After joining the European Union, Greece gained access to easy credit and lower interest rates. With little originality, the Greek government launched an economic development plan based on expanding public spending financed by fiscal deficits and growing public debt. To stay within the Eurozone's financial rules, Greece manipulated fiscal data for years. The true scale of the problem only came to light in 2009, when a new prime minister took office and revealed that the 2009 fiscal deficit was not 6% of GDP, but 13% (later revised to 15%). Immediately, the market began demanding much higher interest rates on new loans to Greece.

In 2010, the country received a bailout package from the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. In return, the government committed to several fiscal austerity measures necessary to rebalance public finances, but which intensified the Greek recession. Even with external aid, the crisis was not controlled, and in 2011 a second bailout package was announced, accompanied by the restructuring of Greek debt held by private creditors. In these situations, restructuring is often a euphemism for partial default. Those holding Greek bonds at the time lost about half of their investment.

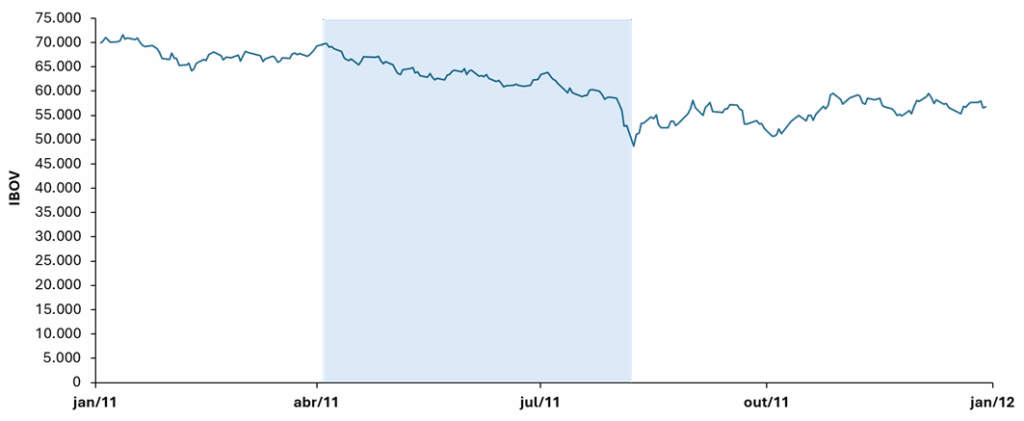

Brazil was affected by the traditional breakdown in trust with emerging countries that occurs when any of them experience severe problems, and by the reduction in exports to the European Union, which was experiencing a recession and was Brazil's second-largest trading partner at the time. The IBOV index fell 30% and took years to recover, as the global economy remained weak for a long period, even in the face of expansionary monetary policies from several central banks in developed countries.

2013: Federal Reserve austerity and protests in Brazil

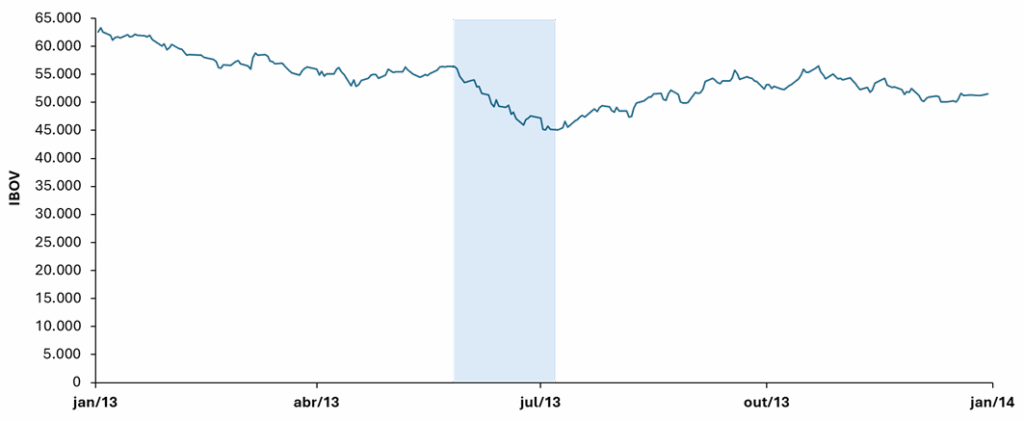

Since the subprime mortgage crisis in 2008, the Federal Reserve has maintained an expansionary monetary policy known as quantitative easing, which involves constant purchases of financial assets to inject capital into the market. In May 2013, the Federal Reserve signaled that it would begin to reduce these asset purchases, which sparked a violent market reaction.

Although Brazil was not directly involved in the problem, the event caused a rise in US interest rates and capital flight from emerging markets. The Brazilian stock market, dependent on foreign capital flows, suffered.

Several internal factors contributed to the problem. Brazilian GDP growth was below expectations, inflation was exceeding the Central Bank's target ceiling, and there was some political turmoil in the country, contributing to the perception of risk. June 2013 was when protests over rising public transportation fares reached their peak and encompassed other issues: corruption, healthcare, education, and excessive spending on the World Cup. These events already indicated the fragility of Dilma's administration, and the IBOV index reached a price of 29% in early July, below its yearly high.

2016: Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff

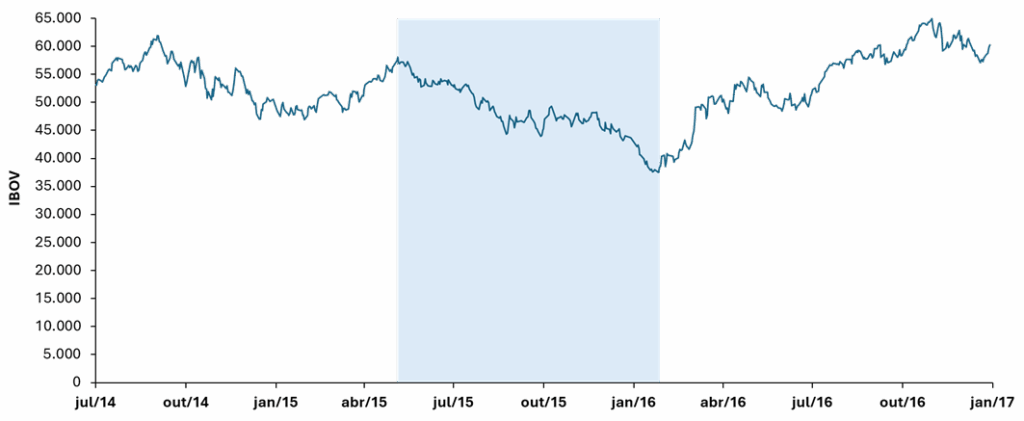

Brazil grew a paltry 0.1% in 2014. In an election year, then-president Dilma Rousseff adopted expansionary measures and postponed fuel and energy price adjustments in an attempt to curb inflation. After a narrow reelection, the hangover of artificialities set in: growing deficits and accounting maneuvers in the public accounts that became known as "fiscal pedaling." The country plunged into recession. GDP declined for two consecutive years (3.5% in 2015 and 3.3% in 2016), and public debt grew from 52% to 70%. Simultaneously, Operation Car Wash revealed systemic corruption at Petrobras and other institutions under federal government control. As expected, the market reacted accordingly.

On December 2, 2015, the Chamber of Deputies initiated impeachment proceedings against Dilma Rousseff. Market pessimism peaked in early 2016, when the IBOV index fell 35% from its previous year's high. In May, Dilma was removed from office, and in August her mandate was definitively revoked. Throughout this process, the market gradually regained confidence in Brazilian institutions, and the IBOV index ended the year 60% above its January low.

2020: Covid-19 Pandemic

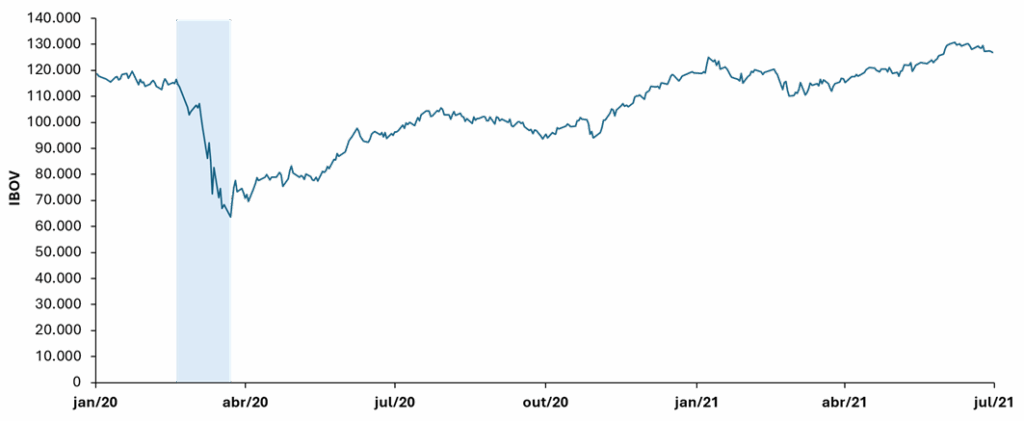

This was the most unusual crisis of the entire period. We were surprised by a new virus that caused severe respiratory problems in some of those infected and spread rapidly throughout the world. In an attempt to contain the spread of the virus, almost all countries restricted the movement of people in public spaces, known as lockdowns. As a result, productivity in various industrial and commercial activities was hampered. Markets panicked, not only because of the economic damage but also because of the uncertainty surrounding how long the pandemic would last and the extent of the damage until it was contained. Stock markets around the world experienced one of the most abrupt declines in history. In Brazil, the IBOV index fell 45% in just over a month.

Responding to the crisis, governments and central banks around the world announced aggressive economic stimulus and social assistance packages, and stock markets recovered almost as quickly as they fell. In the three months following the March low, the IBOV rose 50%. By the end of 2020, the index had already recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

Lessons from past crises

It's remarkable how volatile the Brazilian stock market is. As if domestic problems weren't enough, our dependence on foreign capital makes our stock market vulnerable to any turbulence in the global economic landscape, and our status as an emerging market generates suspicion whenever another country in the same category experiences problems. But, as with almost everything, there's a glass that's half-empty and half-full.

We've had a crisis every three years, on average, over the past few decades. Each one caused substantial wealth destruction for those invested at the peaks before the crashes. However, volatility proved exaggerated in most cases, and in more than half of the crises, the market recovered quickly after falling beyond what was justifiable. The same events that pose a threat also offer extremely profitable investment opportunities.

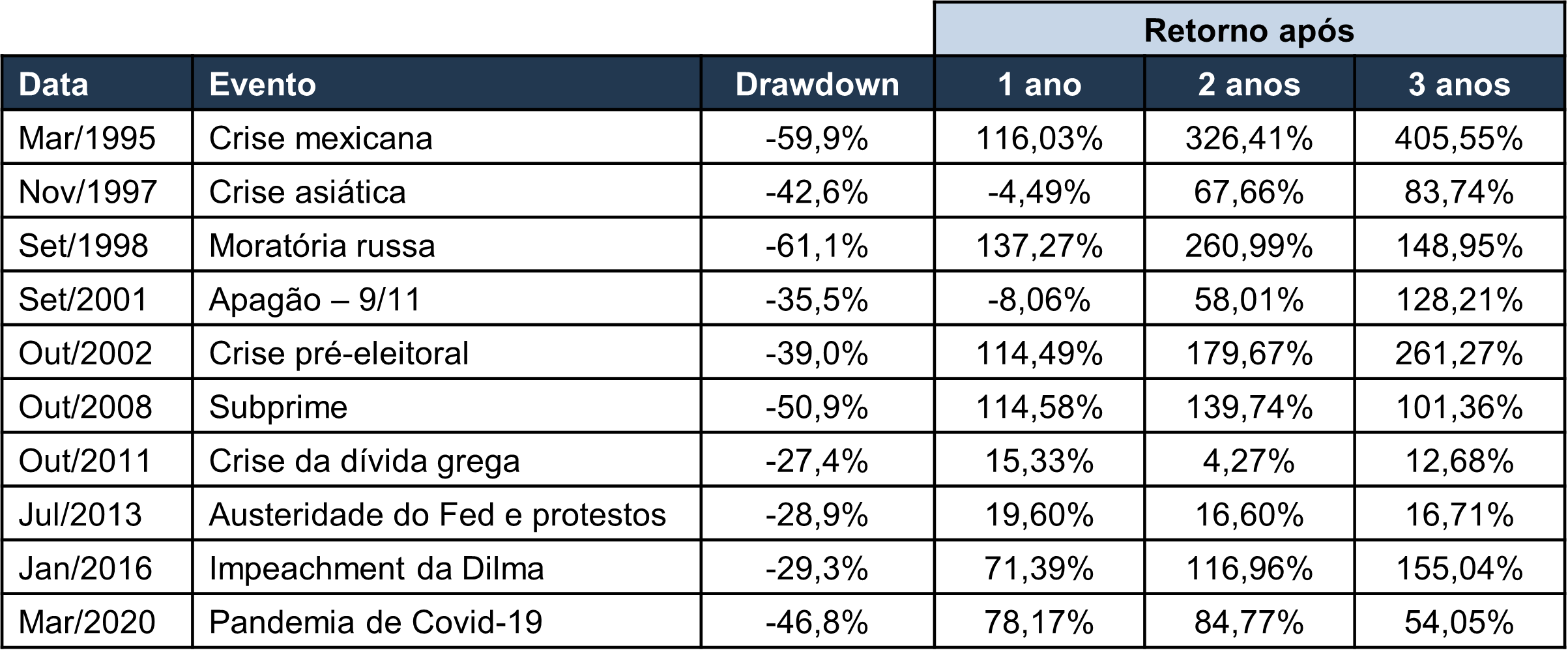

The table below summarizes the IBOV's return in the years following the lows of each crisis. The return was excellent in several of them.

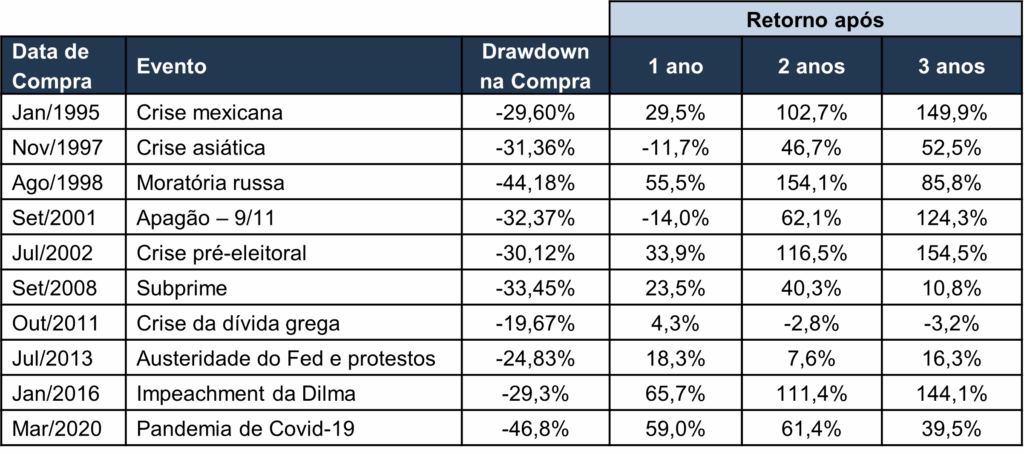

If equal amounts of capital had been invested at these points and held for three years, the average return of this "portfolio" would have been 33% per year. However, this return is entirely theoretical, as it is impossible to know in advance which days would be the lowest point in each crisis. A more accurate simulation considers the entry point to be the moment when the IBOV index reaches a drawdown of 25% and remains below it for five consecutive trading sessions. We assume purchases are made evenly over the subsequent 20 trading sessions. The exit dates from the simulation are completely arbitrary, based on the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd-year anniversaries from the entry point and also assuming sales made over the subsequent 20 trading sessions. The results are summarized in the table below.

Investing the same amount for three years during each crisis, the average return from the simulation would be 21% per year. Not bad for a simplistic strategy restricted to the IBOV index. Theoretical simulations aside, there are two important lessons to be learned from these tables.

The first is that the greatest risk for stock investments isn't present when the economic outlook is bad and the general mood is pessimistic. In these moments, the danger is already priced in. The real risk of wealth destruction exists during moments of euphoria, when investors become careless and the prevailing narratives are rationalizations for why inflated prices still make sense.

The second lesson is that being able to remain coolly rational and act in moments of widespread despair is one of the main sources of return for stock investors. Some legendary investors attribute this ability to some innate factor that shields them from the paralyzing fear that prevents most from buying during downturns. Our view is that, like almost every human ability, this one is part innate and part derived from discipline and training. The experience of having lived through several economic cycles and the discipline of following well-defined principles greatly helps distance oneself from the collective mood of the market.

Where are we today

Recalling past crises provides an interesting perspective for assessing the current scenario. It becomes clearer that Brazil's situation is not as bad as it once was, despite the current problems and the pessimism that still prevails among local investors. Since the pandemic, we haven't experienced any acute crises. The problem is chronic: fiscal imbalances and constant political turmoil have prevented the start of a new bullish cycle in our stock market. From its pre-pandemic peak to today, a period of 5.5 years, the IBOV (Brazilian Index of Industrial Value) rose 11.3%. In the same period, the IPCA (Brazilian Consumer Price Index) varied 37.5%, and GDP saw real growth of ~14%. In other words, the Brazilian economy has advanced, but stock prices have not.

The same image illustrates well what happened to some listed companies: their financial results and share prices advanced at odds, creating attractive investment opportunities. Ártica Long Term has yielded ~2.5x more than the IBOV over the last three years. What we did was simply ignore the political noise and remain focused on seizing this type of opportunity.