The risk of debt in Brazil

Dear investors,

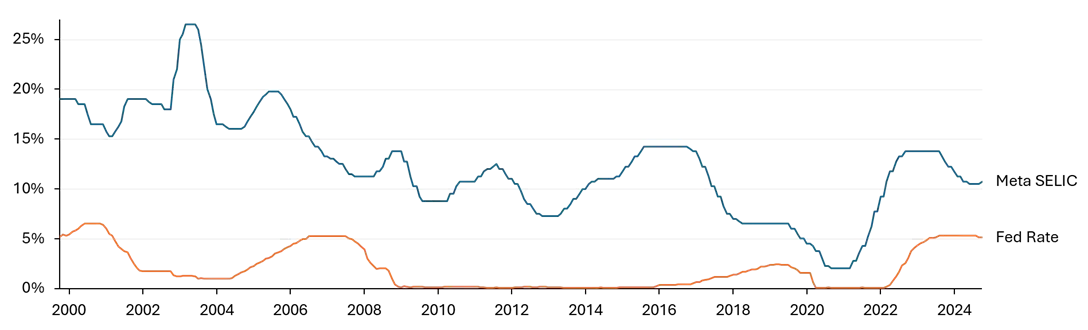

The European Central Bank decided to begin cutting its benchmark interest rate in June of this year. The Federal Reserve followed suit, cutting US interest rates in September. Meanwhile, the Central Bank of Brazil (BACEN) had already been cutting the SELIC rate since August 2023. The early move was consistent because Brazil began its monetary tightening cycle much earlier than developed economies, likely due to its greater experience in dealing with inflation problems. However, a surprise came last month.

Contrary to the global economy's most important central banks, the Central Bank of Brazil (BACEN) decided to reverse the course of interest rates and approved a small increase, from 10.5% to 10.75%. Today, the market estimates that we will return to 12.5%, and some say we will reach 13.75% again. A few months ago, no one was talking about this possibility. We can learn two lessons from this recent history.

The first is that macroeconomic projections are highly unreliable and do not serve as a good basis for investment theses. We wrote about this in February 2022, in the letter "How to Deal with the Macroeconomic Scenario," but nothing like a fresh example to reinforce the point.

The second is that there is wisdom in the culture of traditional Brazilian businesspeople, who prefer to keep their companies' debt levels lower than financial theory dictates. Virtually all of the business literature prevalent in Brazil is imported from the United States, and most of it is directly applicable. However, some points need to be adapted to the local market. The way corporate debt is handled is one of them.

Why almost every company has debt

A company has two main sources of capital external to the business itself: equity, invested by its shareholders, and debt, granted by creditors. A company's primary function is to remunerate this capital invested in its operations at a satisfactory rate, which is called the cost of capital.

A company's ability to generate operating results is independent of the source of the resources invested in its business. The agreement between shareholders and creditors determines only the division of profits. Shareholders want the highest possible return, accepting a certain level of risk, while creditors want the return predetermined in the debt agreements, running the lowest possible risk of not receiving it. Thus, the agreement is that creditors have priority in receiving their share of the profits and, in return, accept a predetermined return lower than the profitability that shareholders expect for the business.

If the company's return is, in fact, greater than the cost of debt, shareholders keep the surplus, and the return on equity will be greater than the return on the business itself. For example, if a company has 50% of its capital in the form of debt and 50% in equity, the cost of debt is 14% per year and the business return is 18% per year, the return on equity will be 22% per year (0.5*14%+0.5*22%=18%). If the business return were 10% per year, the return on equity would be 6%. This is the concept of leveraged return. The greater the share of debt in a company's total capital, the more leveraged the return on equity, for better or worse.

An important detail is that the cost of debt is not constant. The more debt a company takes on, the greater the risk that creditors will not receive the agreed-upon return, as a larger portion of earnings is required to cover interest and debt repayments, and any variation in the company's profitability can cause operating cash flow to become insufficient. Therefore, the cost of debt increases as the share of debt in the capital structure increases.

Theory dictates that ideally, a company should finance itself with debt until the cost of taking on additional debt equals the cost of equity capital. This would be the ideal leverage point, which would generate the best leveraged return on shareholders' capital. We'll discuss whether this point is truly ideal, but it's fair to conclude that it almost always makes sense to have debt, as its cost is usually substantially lower than the cost of equity capital while debt is low.

The Brazilian reality

Theoretical calculations often fail in real-world situations. While even engineers apply safety factors to their calculations to reduce the risk of exceeding the theoretical limit, the same practice applies to business management, which deals with much more uncertain situations. This is especially true for businesses in Brazil.

In the US market, the leverage issue is somewhat easier to deal with. The economy is more stable, and corporate debt typically carries fixed interest rates. Uncertainty surrounding business results remains, but the cash flow required to cover interest and amortization is known from the outset. In Brazil, corporate debt is more commonly post-fixed, indexed to the CDI, and we know how volatile our economy is. The chart below compares the evolution of the SELIC, Brazil's base interest rate, with the Fed Rate, the US economy's benchmark interest rate.

SELIC Target and Fed Rate History

Source: Central Bank of Brazil and Federal Reserve

The difference in stability and the range of variation between the two rates is notable. Brazilian interest rates fluctuate so much that creditors themselves prefer not to take the risk of carrying out fixed-rate transactions, or they demand such a high return premium to cover this uncertainty that most entrepreneurs prefer to take on floating-rate debt, bringing upon themselves the problem of having a fluctuating financial cost over the years.

In addition to the unpredictability of financial expenses, there's an aggravating factor for companies. When interest rates rise, the economy as a whole slows down. It becomes more difficult to increase revenue or pass on prices, and business results tend to be weaker precisely when more cash flow is needed to cover debt interest. Many companies end up unable to meet debt payments and default. With higher default rates, creditors demand an even higher risk premium, and the problem deepens.

The average cost of corporate credit in Brazil (excluding subsidized lines) is around CDI + 10%. With the current SELIC rate, this means that companies would need a return above 20% per year for it to make sense to take on debt. Very few businesses consistently achieve this level of return. Debt with a reasonable cost ends up being only those with real guarantees or endorsements from well-capitalized partners, or raised by very large companies well-known in the financial market. For the rest, the cost of debt in Brazil is prohibitive, and most credit operations end up being undertaken when the entrepreneur has no other option, rather than because it is truly worthwhile.

The common sense of traditional Brazilian businesspeople, that it's best to simply avoid debt, is a sound recommendation in this environment where we have an unstable economy, volatile interest rates, and such a high bank spread.

Why is Brazil like this?

Most business owners blame the banks. Seeing interest rates rise precisely when the company is going through a difficult period, they say that the banks' lending logic is to rent an umbrella when it's sunny and ask for it back when it starts to rain. In turn, the banks blame the business owners, who plan poorly, manage their businesses poorly, and generate a level of default that requires high interest rates to keep the credit operation viable. The tendency to point the finger at the immediate counterparty is understandable, but the problem stems from a broader context.

The bank operates as necessary for its own business to be profitable. Entrepreneurs take on debt when they believe they will achieve a sufficient return or when there are no alternatives to keep their business afloat. The problem is that making accurate financial plans in an economy where the benchmark interest rate has fluctuated between 2 and 14% over the past 5 years is like building a house of cards on a rocking chair.

The necessary solution is for the economy to be managed more stably, with a government that adopts more conservative fiscal practices and a central bank that prioritizes market stability. However, we are aware that this statement is like the insight of a young manager who concludes that the solution for a struggling company is simple: increase revenue and reduce costs. We don't have high expectations that the Brazilian economy will improve any time soon, and pragmatism leads us to simply accept that this is the scenario we must deal with.

How to invest in this environment

Due to high interest rates and economic uncertainty in Brazil, many people conclude that investing in debt securities is best. However, both debt and equity are subject to the same business risks related to the invested company. The difference is that equity serves as a buffer against potential losses imposed on creditors. This protection works well when earnings fluctuations are small, but it is ineffective in extreme cases, where the company files for bankruptcy protection and requires creditors to write off part of the debt to enable business recovery (again, see the case of Americanas). It's like wearing a seatbelt, which reduces the risk of injury in a collision, but is much more effective in a car accident than in a plane crash.

Because fixed income is very popular in Brazil, it's common to see credit securities with lower return premiums than we believe would be appropriate for the related risk. Pricing sometimes seems to ignore the possibility of more serious problems, which would affect both shareholders and creditors. Therefore, our preference is to invest in stocks, with direct exposure to business risks but without the contractual return limitation that fixed-income securities have.

Knowing this risk exposure and the volatile economy, investments in businesses that would yield excellent returns in a stable environment can be a trap. Even when everything seems to be going well in Brazil, making it clear that this is not the case today, it is unlikely that we will go many years without a new crisis. Therefore, we seek to invest in businesses that are capable of weathering varying macroeconomic scenarios without collapse. Generally, this means avoiding highly leveraged companies.

There was a time when several American business schools argued that companies should pursue their optimal capital structure, which generally resulted in high leverage. It was even argued that indebted companies were better managed, as executives were obliged to maintain the cash flow discipline required to meet interest and amortization payments. A famous analogy compared this logic to the assertion that drivers would drive more cautiously if a knife were stuck in the steering wheel and pointed at their chest.

Warren Buffet criticized this line of thinking, saying that no one in their right mind would put a knife to the steering wheel to drive better, because even if it reduces the risk of accidents, any minor collision can pose a risk of death. The same goes for companies. Situations that an unleveraged business would navigate without major problems could lead a heavily indebted one to bankruptcy.

We believe that the more uncertain the economic outlook, the more important it is to prioritize resilient results, rather than seeking theoretical optimums. Overleveraging in Brazil is like putting a knife in the steering wheel and driving on a potholed dirt road. Not very wise.