The Hard Side of Value Investing

Dear investors,

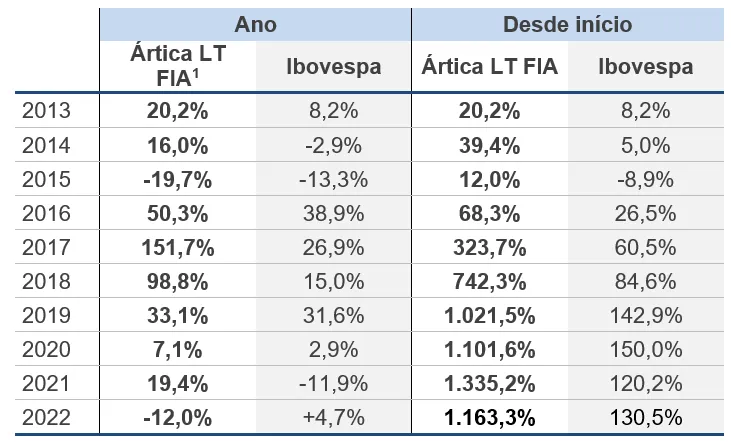

We ended 2022 with a return of -12.0% for the year, compared to +4.7% for the IBOV and -15.1% for the SMLL (small cap index). The cumulative return since the fund's inception, approximately 9 and a half years ago, is 1,163%, representing an average return of 30.7% per year (vs. 9.2% per year for the IBOV):

During this period, we maintained our traditional strategy: identifying companies with resilient businesses and historically high profitability and buying their shares when prices were low. We began our buying season in the last quarter of 2021, when some stocks reached a price level that already seemed attractive to us, and we have continued to execute gradual purchases until now.

Knowing the price trajectory of the stocks we chose to hold in our portfolio, we started buying about three quarters earlier than would have been ideal. We don't think we overpaid for any of our positions, but it certainly would have been better to wait and buy the same stocks at even lower prices than we initially paid.

Missing the best timing is one of investors' eternal curses. Because it's impossible to predict stock price movements in short periods, it's expected that the execution of purchases and sales will always be suboptimal. But even when aware of this, it's always unpleasant to calculate how much better the execution could have been.

Building on this positive tone, in this letter we will discuss the difficulties of investing following a truly long-term fundamentalist philosophy and what we understand is necessary to do so successfully.

Macroeconomic uncertainty

When we read today's headlines, at first glance they may seem worrying. In Brazil, the new government has shown little concern for fiscal responsibility, increasing spending beyond the ceiling without clear revenue counterparts, which could result in an increase in the public debt-to-GDP ratio, which is already quite high for an emerging country. Globally, we see signs of a slowdown in major economies, resulting from more restrictive monetary policies adopted by Central Banks after years of low interest rates. Furthermore, international economic relations have been reviewed following the geopolitical conflicts occurring worldwide, which could lead to a reorganization of supply chains, taking into account political stability and predictability in favor of efficiency and economic productivity.

However, we've been through much worse periods, and yet stocks have enjoyed strong gains in subsequent periods. Newspapers are filled with explanations of what's happening in the economy, but it's much easier to understand the logic of the past than to predict the future. We're quite skeptical about the possibility of predicting macroeconomic movements, especially given the number of random factors that affect the economy over time. No one predicted the pandemic and the war in Russia and Ukraine, the sources of much of today's macroeconomic problems.

Economists typically label these events as non-recurring and explain that their projections would have come true had these extremely rare events not occurred. However, the question isn't how often a pandemic or a war with global geopolitical impact occurs, but rather how often any unpredictable event with significant economic impact occurs.

Random factors can be both good and bad. Sometimes, a new technology emerges that dramatically increases productivity in a given sector. In other cases, a climate change causes one country to have excellent harvests while another has terrible agricultural productivity. The country with abundant harvests may benefit from GDP growth, a favorable trade balance, and currency appreciation, without any merit other than being in a place where rainfall was just right. This already illustrates the difficulty of working with macroeconomic projections. If you need further convincing, our February 2022 letter We analyzed the accuracy rate of macroeconomic variable projections in the expectations system compiled by the Central Bank of Brazil. In short, it's far from good.

How to deal with uncertainty

Being aware of unpredictability is better than having the illusion that the future is predictable. If you have to choose a vehicle for a 100km race on unfamiliar terrain, it's better to choose a horse, which can go anywhere, than a Ferrari, which only runs on asphalt. Depending on the track, you may not finish first, but you'll finish the race.

The essence of the investment strategy is the same: without knowing what we'll face, the best decision is to prioritize investments in companies that are capable of continuing to operate under a wide range of possible scenarios. This requires that their businesses be adaptable to different macroeconomic scenarios or operate in naturally stable market sectors.

Drawing on examples from our own portfolio, Multi is an adaptable business, as its expertise lies in importing finished products or components (particularly from China), assembling them, and distributing them in Brazil, remaining reasonably agnostic to the specific products in question. The company currently handles over 7,000 items, with a portfolio profile quite different from what it was five years ago. Our thesis hinges more on Multi's ability to continue executing the cycle of selecting, importing, and selling new products than on the specific performance of the company's current products.

Whirlpool, the manufacturer of white goods for Brastemp and Consul, is an example of a business operating in a stable market. The white goods sector has a very slow technological evolution (think about how much your refrigerator has changed in the last 10 years), where brand is a very important decision-making factor for consumers, and cost efficiency depends heavily on scale. Therefore, few companies dominate this sector worldwide, and we haven't seen major changes in the organization of this industry in recent decades.

The tricky part of this strategy is that businesses with this profile won't always outperform other potential investments. In 2022, several commodity-related companies outperformed our portfolio, but we resisted investing in these sectors because the risk associated with future commodity price declines seemed significant. In our imaginary race, if the first 50km were on a road, you'd hate yourself for choosing the horse and only rejoice when you came across a stream to cross.

Although our two examples didn't have their best year in 2022, they are solid businesses that continue to generate profits even in this difficult environment and are well-positioned to expand their results when the economic scenario recovers. Improvement will certainly come, although we don't know exactly when, as the cyclical nature of the economy is well known. The question you may be asking is: why hold or buy stocks during downturns, rather than wait for the crisis to pass? Excellent question.

The pain of buying low

We like to buy stocks at prices significantly below our perceived value. This is only possible during downturns, amid bad news and widespread market pessimism, when some investors lose faith in companies and decide to sell their shares at any price. No one is willing to sell us shares at deeply discounted prices when the macroeconomic outlook is positive, the company is delivering excellent results, and the market sentiment is excellent. Buying at a very low price requires facing negative scenarios.

Some say the trick is to wait for the market to start recovering before buying, but that advice is as effective as the recommendation to buy low and sell high. Obviously, this would be a good tactic if it were possible to know the exact moment in the economic cycle we're in today and if no one else in the market had the same awareness of that moment. In real life, opportunities to buy at a very low price disappear when macroeconomic uncertainty subsides. It's this problem of pinpointing the exact moments in economic cycles that makes us long-term investors.

It's easier to accurately estimate how much rainfall will fall over the next five years, based on historical rainfall averages over time, than it is to reliably estimate how much rainfall will fall in a given week a few months from now. Similarly, it's easier to estimate that a company will generate a certain level of earnings over five years than to accurately predict a specific quarter's earnings. Therefore, our investment theses assume we'll remain positioned for a long period, making it likely we'll experience both good and bad macro periods. With the expectation of navigating this entire cycle, it's much more favorable to buy during stress scenarios, when prices are lower, and have the patience to wait for things to improve. It sounds simple, but it's harder than it seems.

Fall resistance

It's rare to be lucky enough to buy at the exact moment the price trend is reversing, so that the stock only rises after the purchase. When buying in the midst of crises, it's more common to have to watch your stock fall for some time. This requires both analytical skill and a good dose of psychological resilience.

Analytically, performing a thorough assessment of the invested company's true value is what gives you the confidence to maintain your position based on a thesis. If you know something is worth around $100, bought it for $70, and saw the price drop to $50, you might regret not waiting longer to buy everything at $50, but you have the comfort of knowing that $70 was still a good price (this example sums up our current situation). Without this reference to true value, investing would become an agonizing game of chance.

Even with this analysis in hand, maintaining an investment means watching price drops day after day, amid a barrage of negative news and numerous people saying this is one of the worst crises of all time and that there may be no recovery because "this time is different." Not allowing oneself to be overwhelmed by excessive emotions and remaining purely rational during these times is a test of discipline and temperance. It's necessary to distance oneself from day-to-day life and look back to understand how history unfolded during other crises. Reasonable expectations are usually less extreme than newspaper headlines suggest: there's always something different in each case, but the same dynamics of economic cycles have been observed countless times. As Mark Twain said, "History doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes."

This practice becomes easier over time. Today, after nearly 10 years of investing through Ártica Long Term, we tend to enjoy times of crisis, because these are precisely the times when we can invest in new ideas at significantly depreciated prices.

Tendency to act

Executing a long-term, fundamental investment strategy is also difficult because our instincts are designed to react quickly to each new stimulus in the environment, rather than to navigate a cycle that develops slowly over several years.

In turbulent times, the temptation is to move too much. Many investors nervously alter their portfolios, reacting to every new newspaper headline. It may seem diligent to move with every new development, as it's part of the job to incorporate new information into analyses, but it's not every day that something emerges that will truly impact the long-term outcome of a thesis. In most cases, the impact of new developments is overestimated, and unnecessary movements are made, rendering the investment strategy incoherent and increasing transaction costs.

Doing nothing isn't easy when it contradicts our impulses. Calmly waiting for market turbulence to pass, observing the market's desperation and frenetic movements, requires self-control analogous to that required for dieting. Losing weight, in theory, is easy and doesn't require any action: just don't eat. The hard part is staying quiet while starving.

The way to counter instinctive impulses is to rely on pure rationality. We know that a country's economy depends on such a large set of agents, has such complex governance, and is impacted by so many random events that it's not easy to steer it, voluntarily and in a planned manner, in any direction, for better or for worse. Except for the effects of major events that occur from time to time, things tend to change slowly. So, there's a certain dissonance in abruptly changing one's mind about the future at any given moment.

Lack of feedback

Another challenge faced by long-term investors is the limited amount of feedback they receive over the years on their investment theses. Unlike learning to play a musical instrument, where each mistake is immediately apparent and a new attempt can be made soon after, an investment thesis can take years to prove itself right or wrong. A fundamental investor will typically execute only a few dozen theses in their lifetime. Therefore, the possibility of empirical learning is quite limited, making trial and error a poor method for learning to invest.

Investing well requires a quasi-academic life, of continuous study and a conviction derived from accumulated knowledge and rationality, which is different from the conviction we have when executing something we've done hundreds of times and seen the same result over and over again. It's necessary to maintain this "academic conviction" to avoid letting instinct prevail in critical moments and to be able to continue acting rationally and consistently. Napoleon Bonaparte said that a military genius was one who could act mediocrely while everyone around him was losing their minds. We believe this same logic applies to the world of investing.

Perspectives for the Arctic Long Term FIA

We purchased most of our current holdings over the past five quarters, going against the grain of the broader market. We're aware of the current macroeconomic risks, and have even explored some of them in our last three letters. However, because we purchased our shares at such low prices, we have good return prospects even if the economic environment takes a few years to recover.

As there is still considerable uncertainty regarding the new government, especially the impact its policies will have on the yield curve, it is unclear whether we will see any recovery throughout 2023. However, Brazil has gravitated toward centrist policies for several decades, so we continue to consider this scenario as a base case. The public's own reaction to the government's unorthodox moves tends to influence them toward a more lenient course of action.

In any case, we will remain attentive to the evolution of the country's economy, monitoring whether the deterioration predicted by so many will actually occur, but without allowing ourselves to be influenced by the extreme political discourse that has persisted since the presidential campaigns.

We remain confident in the quality of the companies we currently hold in our portfolio and their potential returns. As our greatest demonstration of our faith, we made a substantial volume of new equity contributions to Ártica Long Term throughout 2022, supported by several long-time investors and some new investors we were pleased to welcome. While several equity funds experienced massive waves of redemptions, Ártica Long Term closed the year with approximately R$1.4 billion in net inflows.