What if the stock market keeps falling?

Dear investors,

In April, the IBOV fell 10.1%. Prior to that, the index had risen 17% between the beginning of the year and its peak on April 1st. The price of our share in Ártica LT FIA also fell 6.1% last month and has fluctuated significantly since the beginning of the year, so we'll dedicate this letter to a topic that couldn't be more relevant: stock price declines.

We've mentioned before that we experience periods of low prices with a more positive mood than the market as a whole. Our motivations for this stance seem almost obvious once understood, but they receive so little attention that we thought it would be beneficial for our readers if we presented them in more detail.

The Paradox of Multiples

When we buy stocks, there are only two ways to get some money back: i) receive dividends (or interest on equity) and; ii) sell the shares. The amount of dividends distributed depends on how much profit the company generates over time, and the price at which the shares can be sold depends not only on the profit generated but also on the market's expectations regarding the business's future growth and profitability, which, in simplified terms, we will assume is represented by the ratio between the valuation attributed to the company and the value of its net profit, that is, the company's P/L (Price/Earnings) multiple.

Assim, para termos bons retornos, deveríamos desejar que nossas empresas gerem o máximo de lucros possível e que seu múltiplo de P/L aumente ao máximo, certo? Pense por um minuto em qual é a falha deste raciocínio…

Evaluating only the return on a specific investment, this logic works perfectly. However, what we seek is not the maximum return on a specific investment, but rather the maximum return on our entire wealth over our lifetimes. With this goal in mind, the desire for our invested companies to generate as much profit as possible remains, but the second factor is reversed: the lower the Price/Earnings multiple becomes, the better, assuming the reason for the decline is not linked to some setback in the invested company. We'll explain why.

The cheaper the better

Initially, when we begin buying shares of a given company, we should obviously want the share price to be as low as possible relative to the company's ability to generate future financial results (in short, the lowest possible P/E multiple). As long as we have the capital available to buy more shares, this logic holds, and we should expect the share price to fall over the course of our purchases.

This point generates some psychological discomfort for many investors, as seeing the stock they're buying falling gives the impression that the initial purchases were made at a high price. However, assuming the initial purchase decision already considered the price attractive given the company's expected cash generation, the falling share price makes the investment opportunity even more attractive and should be viewed favorably by investors.

Having settled the point that buyers prefer low P/E multiples, the next argument is more subtle. Even after allocating all available capital and being unable to continue buying, a long-term investor should still consider themselves a potential buyer and prefer low P/E multiples, as invested companies will pay dividends over time, and the dividends received will need to be reinvested by purchasing more shares.

In general, when multiples of valuation of listed companies are below average, this is an opportune time to invest in shares, as the expected return on purchases made at attractive prices is, naturally, higher than average.

To the unbelievers

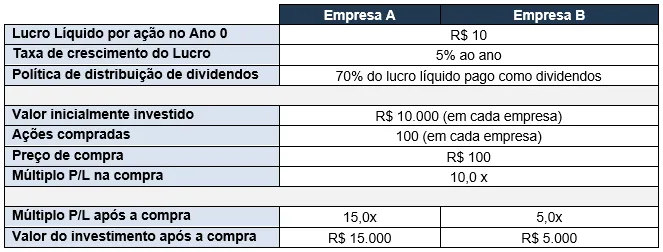

If you're not convinced, consider the following example, where an investor buys 100 shares of two identical companies, with just one difference: Company A's valuation rises by 50% shortly after the purchase, and Company B's falls by 50%.

Assuming that the valuation multiple, which changes immediately after the purchase, will remain the same forever, and that the investor will use the dividends received to buy more shares of the company that distributed them, let's observe how the investor's equity evolves in each of the companies.

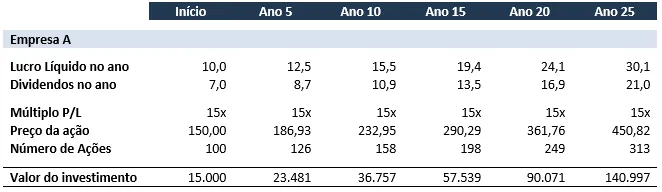

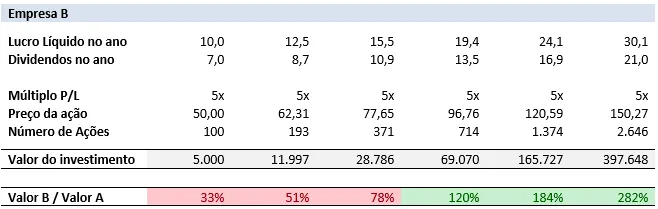

Even though, in Company B, the investor starts with a loss of 50% and a value equivalent to 1/3 of the shares in Company A, he is able to buy more shares in Company B with the dividends distributed by it, due to the valuation much lower. Over time, Company B becomes an increasingly better investment and outperforms Company A.

It's impressive how, even with such a sharp difference in multiples, in the long run the benefit of buying more shares at attractive multiples, using the business's own dividends, outweighs the benefit of a higher valuation multiple.

The secret is to buy cheap

The conclusion of the above analyses is obvious: buying low is good. But there's a less obvious continuation of this statement: buying low is always good, regardless of future price movements. If the stock becomes even cheaper, we'll fall into the example of Company B. Furthermore, it's impossible to predict short-term price movements, which makes any buying or selling policy based on an opinion about market price movements over a period of months ineffective. For these reasons, we adopt the practice of buying shares whenever we find good deals at attractive prices, ignoring the current "market mood."

Note that there's a vital point to be made in this approach. To buy cheap stocks, you need to know which prices are cheap. We're using the P/E multiple in the examples in this letter, but this is a vague reference point for a company's valuation. Assessing a company's worth is always more complex than simply looking at the historical P/E multiple and comparing it to the current P/E multiple. Essentially, each investor must estimate each company's long-term financial results and discount the cash flow generated by each business at a rate of return they deem appropriate, only then having a value benchmark against which the stock price can be compared and considered cheap or expensive.

Even if a good purchase price is guaranteed, the investment will only yield a poor return if the future of the invested company is worse than estimated at the time of purchase. The instantaneous price of a stock receives excessive attention, due to our constant desire to quantify the value of our investments, but it only matters at the time of sale, and selling is not mandatory. We can hold shares in our portfolio for as long as we see fit.

If stocks become expensive

When an invested company reaches levels of valuation When the stock's price is high, we begin to consider selling it. However, the reason for selling shouldn't be the share price itself, but rather the opportunity to reallocate invested capital to businesses with expected better returns. In other words, it only makes sense to sell when an investment opportunity is identified with an additional expected return sufficient to cover the transaction costs of this reallocation of resources.

Note that this need to reallocate capital invested in a company that has become expensive is a good problem to have, as the reallocation is completely optional. If we do nothing, the expected return should still be approximately what was estimated at the time the shares were purchased, assuming the invested business hasn't undergone major changes.

That's why we place such emphasis on the importance of buying good companies at attractive prices. The quality of the business ensures its long-lasting and profitable value, and the low purchase price ensures a good return regardless of the valuation multiples. valuation in the future.