How we build portfolios

Dear investors,

In the last two letters, we wrote about how we seek investment opportunities and how we analyze the risk involved in each one. In this one, we will address the final step: how we combine these isolated opportunities into a coherent investment portfolio for our funds.

The goal is to allocate capital to the best opportunities available at a given time, without exposing it excessively to the risk of losses. Approved investment theses need to be compared to determine the appropriate percentage for each, so we need a method that allows us to make this comparison consistently. We also need to control the risk level of the portfolio itself, resulting from the grouping of selected theses and defined allocation levels. We will explain below how we address these issues.

How to compare investment theses

The theory of how to compare investment theses is trivial: simply compare the potential returns and risk levels of each. The thesis that offers the highest return per standardized unit of risk is the best. The practical problem is that there is no categorical method to determine these two variables of interest with precision.

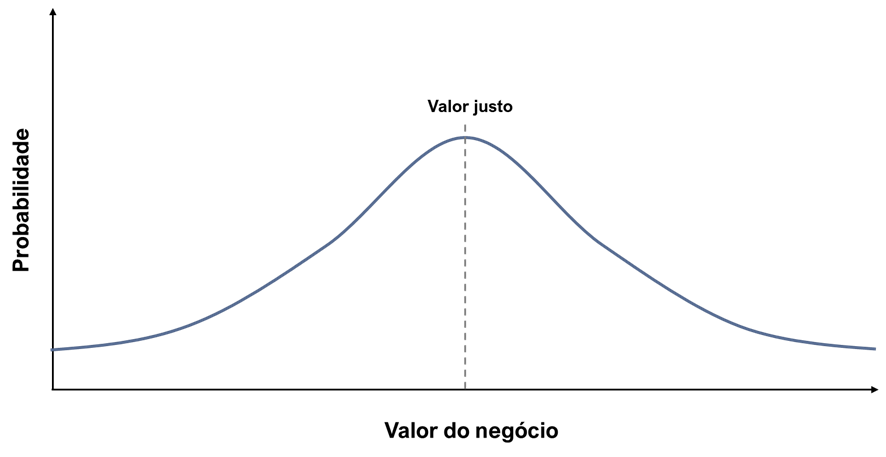

For each investment thesis, we develop a financial model that simulates the future results of the business and allows us to calculate the company's value, discounting its expected cash flow. Since this model depends on a number of uncertain assumptions, the calculated value is equally uncertain. Saying there is a single fair value for the business is a conventional oversimplification. The more realistic view is that there is a spectrum of possibilities for what the real value of the company could be, depending on what happens in the future. By running several simulations varying the most relevant assumptions, we would have a curve of possible values similar to this:

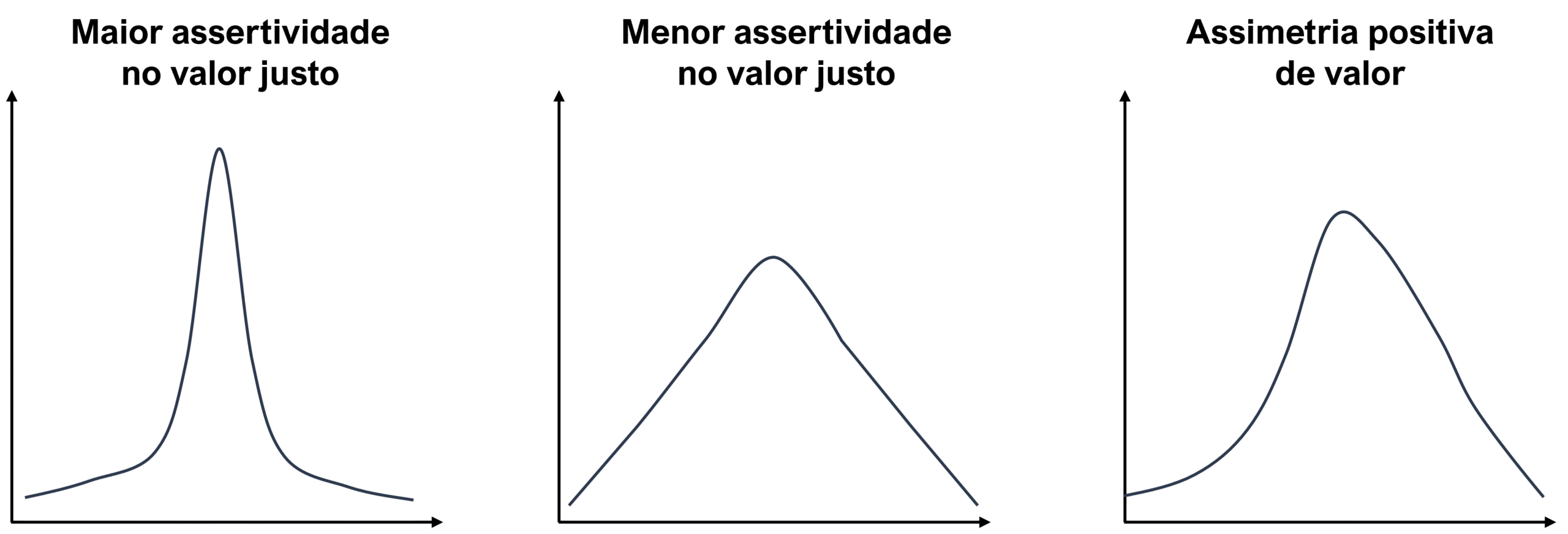

What we call fair value is the average of this probability distribution, but that's not the only important information. The shape of the curve is also relevant. Narrow curves mean that the business being valued is stable and the accuracy of the projections is higher. Wide curves mean greater risk. There are cases where the curve is asymmetrical, sloping towards either gains or losses.

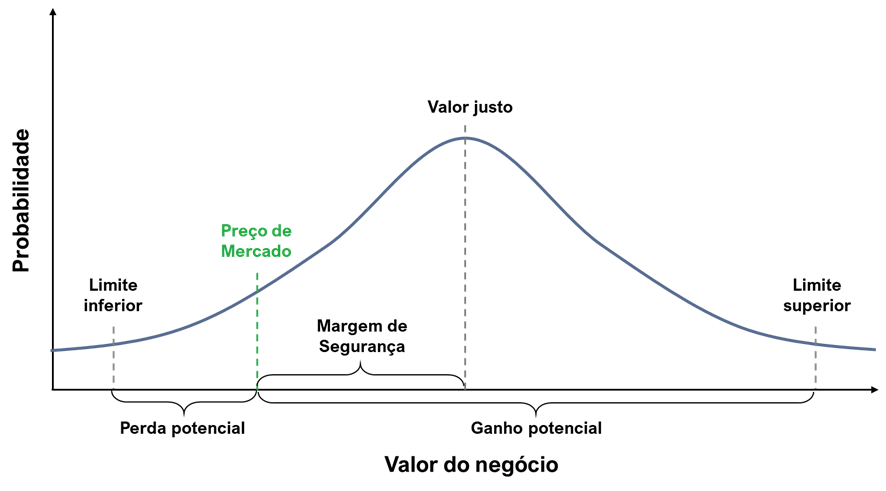

We simplified these results for everyday use as follows: what matters is the range of most probable values, so we can exclude the "tails" from the graph and keep the interval that represents ~90% of the probability distribution. Instead of having only the average value as a reference, we maintain three points: the average, the lower limit, and the upper limit. Thus, we can evaluate the risk-return relationship of each investment thesis by comparing the market price with these reference points. The price discount relative to the average value is what we call the margin of safety, and the difference between the price and the upper limit divided by the difference between the price and the lower limit establishes the relationship between potential gain and potential loss, as illustrated below.

With these analyses completed, comparing the two theories becomes trivial again. The greater the margin of safety and the higher the ratio between potential gain and potential loss, the better the thesis.

In parallel with this quantitative analysis, we also evaluate the qualitative aspects of companies according to a list of pre-established criteria. For example, level of competitiveness in the business segment, strength of competitive advantages, threat from different risk factors, growth potential, etc. For each of these, the company receives a score on a standardized scale, and the set of individual scores makes up an overall score that represents our view of the quality of the business. This methodology is known as scorecard, permite compararmos fatores difíceis de quantificar diretamente, mas ainda relevantes para as decisões de alocação.

By comparing the quantitative factors and qualitative scorecard scores of each company, we ranked the approved investment theses according to their attractiveness and were able to get an initial idea of which ones should receive greater or lesser capital allocation. To define the percentages that each thesis will represent, further steps are needed.

Individual allocation limits

There are two factors that limit the size of a thesis in our portfolio. The first is the liquidity of the stock. We need to maintain the funds' ability to return our investors' capital when requested, so each investment should be limited to the maximum size that can still be sold on the market within the funds' redemption period. The second is the risk of loss that the thesis carries, regardless of its potential for gain.

Imagine an investment that could result in an 80% loss of invested capital in an unfavorable scenario, but, on the other hand, could multiply the initially invested value tenfold. The ratio of potential gain to loss is quite favorable. The opportunity is attractive, but it wouldn't be prudent to allocate a very large percentage of the portfolio to it due to the significant risk of loss. As a rule of thumb, we define the maximum percentage of the portfolio we are willing to allocate to the investment thesis in question and limit the investment size accordingly. For example, if this limit is 4%, this hypothetical thesis could receive a maximum allocation of 5% (5% x 80% = 4%). If the potential loss were 25%, the maximum allocation would be 16%.

These limits, especially the maximum portfolio exposure to a single investment thesis, make it necessary to distribute capital among several theses. This is the famous diversification, which is advocated as a way to mitigate investment risks.

Effective diversification

It's easy to understand the reason for diversification by imagining a series of dice rolls. In just 5 rolls, it's difficult to predict how many times the number 6 will come up. In 6,000 rolls, it's very likely that a 6 will come up approximately 1,000 times. This is a statistical principle known as the Law of Large Numbers: the larger the number of samples, the more stable and predictable the average result will be.

The rationale for diversifying investments is analogous. If we have several investment opportunities with uncorrelated returns, the portfolio's actual return will approximate the return calculated from the expected values for each thesis (assuming the estimates are correct). The important point to keep in mind is that investment theses are not replicable events, like dice rolls, and the existence of a large number of theses with similar risk and return profiles is a purely theoretical ideal. In practice, we find few attractive theses, and their quality declines rapidly. That is, the tenth best thesis is already considerably worse than the first. For this reason, it is necessary to seek a balance between sufficient diversification to control risk and concentration on the best theses to make the portfolio's potential return attractive.

We choose to maintain between 5 and 15 investment theses in our portfolio, depending on the number of sufficiently attractive theses we find each season. When the stock market is down, it's easier to find several viable investment opportunities and diversify the portfolio more. When the market is up, it's harder to find good investments, and our portfolio tends to become more concentrated.

Our target number of positions is relatively small compared to what is practiced in the market, but the strategy is quite deliberate. The benefit of diversification diminishes as more and more theses are added to the portfolio, while the quality of the additional theses becomes progressively worse. From a certain point, adding a new thesis to the portfolio increases the portfolio risk even considering the greater diversification benefit, due to the lower quality of the company.

Because our portfolio is concentrated on the best investment theses, we need to ensure that they are not strongly correlated with each other, in order to keep the risk level under control. It's not enough to assess whether the companies are in different economic sectors. We map which variables have a significant impact on each thesis and take care not to concentrate the portfolio on companies that are heavily dependent on the same economic variables. To illustrate, imagine a city entirely focused on tourism. If you invest in a gas station, a restaurant, a hotel, and a clothing store, all your businesses will still be highly dependent on the same factor: the number of people who will visit that city during the season.

With the list of approved ventures ordered by attractiveness, their individual limits established, and an understanding of the correlation between the businesses, we can define what portion of the portfolio will be allocated to each opportunity. This allocation process is dynamic. As market prices change all the time and the businesses themselves undergo transformations, it is necessary to reassess the portfolio from time to time.

Monitoring and rebalancing

If we assumed that the estimated values for each company were accurate information, it would make sense to rebalance the portfolio frequently, even in the face of price variations of only a few percentage points in the invested companies. However, investing is far from being a precise activity. Value estimates are rough, and there is a lot of noise in price variations, so rebalancing too frequently would increase transaction costs and consume team time without a high probability of increasing the total return of the portfolio.

We remain attentive to new information relevant to our investment theses, but we only rebalance the portfolio when there are significant changes in expectations for one or more of our invested companies, or when there is a significant variation in their market prices. To prevent this dynamic from making us lenient, from time to time we conduct a general evaluation comparing all invested theses with each other and with investment theses that were approved but did not enter the portfolio due to market price or correlation with another invested thesis. The exercise is as if we were building the portfolio from scratch and is a good way to ensure that the allocations maintained are the result of rational decisions, and not a lack of rebalancing.

Even with all possible precautions, every investor knows that it's impossible to pinpoint the exact moments to buy and sell each stock. Trading near historical highs or lows depends much more on luck than skill. Our goal is to buy and sell within price ranges where these decisions are justifiable. By doing this consistently over the last decade, we have been able to deliver attractive returns for our investors, and we expect this approach to continue generating excellent results in the future.