How to deal with the macroeconomic scenario?

Dear investors,

At the beginning of this year, the market turned its attention to Brazil's macroeconomy. With high interest rates and political uncertainty expected throughout the year, the hot topics are interest rates, inflation, exchange rates, GDP, and elections. This scenario is causing Brazilian investors, both institutional and individual, to shift their capital from the stock market to fixed income, while, interestingly, foreign investors are on the other side of the transaction, buying shares on the Brazilian stock exchange. In this letter, we'll explain which side we're on.

Interest and the Stock Market

As a rule, investors buying stocks demand an expected return that is always above the base interest rate, as they are subject to more risk by buying stakes in companies than by buying fixed-income securities. The higher the return required by the investor, the lower the price they are willing to pay for a stock, as the main methodology for estimating a company's value is based on projecting how much cash the business will be able to generate each year and discounting this cash flow by the investor's target rate of return. Thus, the higher the target return, the greater the discount applied to the cash flow and, consequently, the lower the resulting price estimate for the company.

Thus, when the benchmark interest rate rises, the required return on equity investments also rises, and the practical effect is that the market starts to price stocks lower, causing the stock market to fall. This logic may seem to justify the transfer of capital from the stock market to fixed income, but note that the move only makes sense if done before interest rates rise, because, after the rise, the stock market has already fallen, and you would be selling cheap shares. In turn, making the move before interest rates rise raises a more fundamental problem: how do you know when interest rates will rise?

Because of this problem, we follow an investment philosophy not based on macroeconomics. We use the example of interest rates, but it extends to other macroeconomic factors and is a bit more complex: the market already considers a projection of how interest rates will evolve over the years, so we would need to know when interest rates will rise (or fall) with more precision than the market already considers in its expectations. To illustrate how difficult it is to project macroeconomic variables, let's evaluate the accuracy rate of experts over the last 20 years.

Expert projections

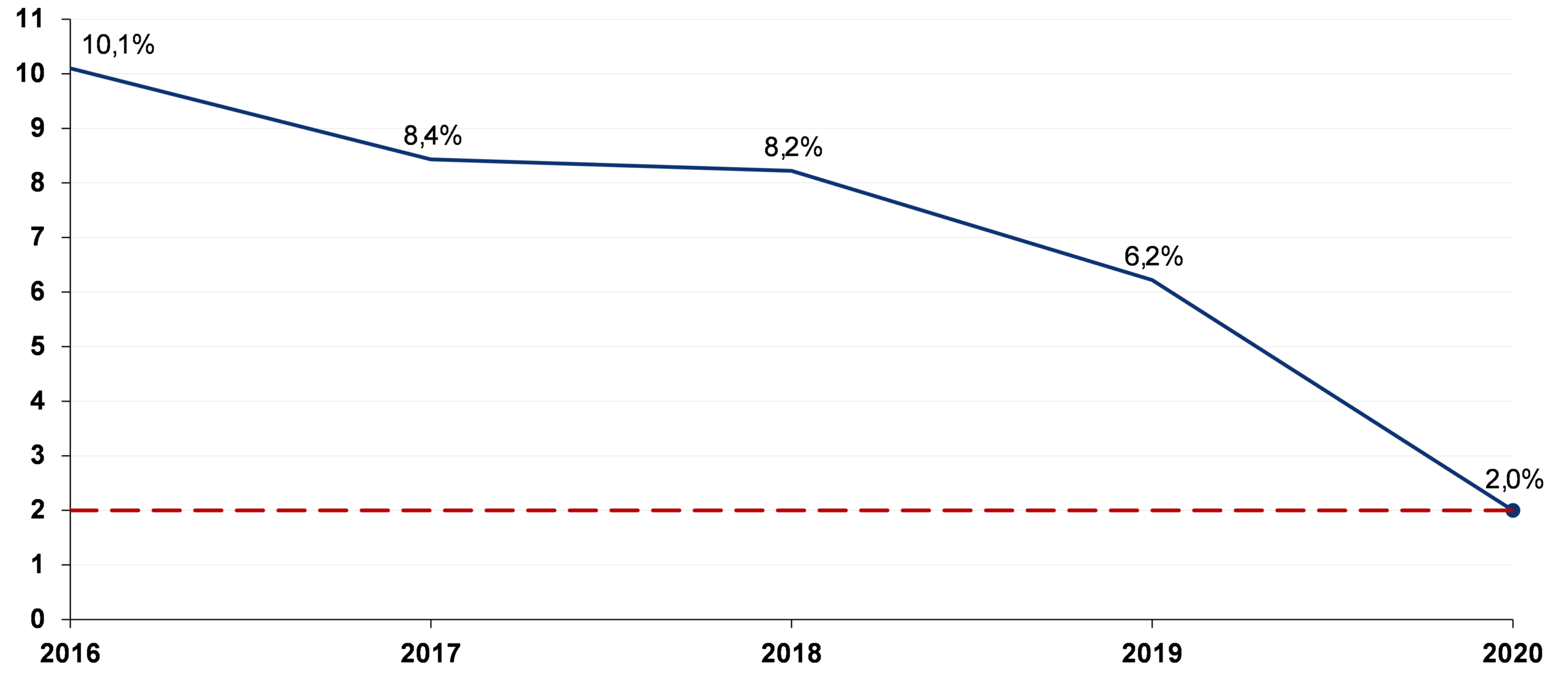

We analyzed data published by the Central Bank's Market Expectations System, which collects daily forecasts on macroeconomic variables produced by approximately 130 financial market institutions and consolidates these data into statistical series. With this information in hand, we verified the market's projected value four years prior to the projection date. See this example illustrating the logic behind graph construction, considering the projection only for the 2020 SELIC rate.

The interpretation of the graph below is: in 2016, the market projected that the 2020 SELIC rate would be 10.1%, in 2017, it projected that it would be 8.4%, and so on, until 2020, when the realized SELIC rate was 2%. Note that, if the market had correctly predicted the realized rate during the previous four years, the graph would be the dotted red line.

Projection for the 2020 SELIC rate

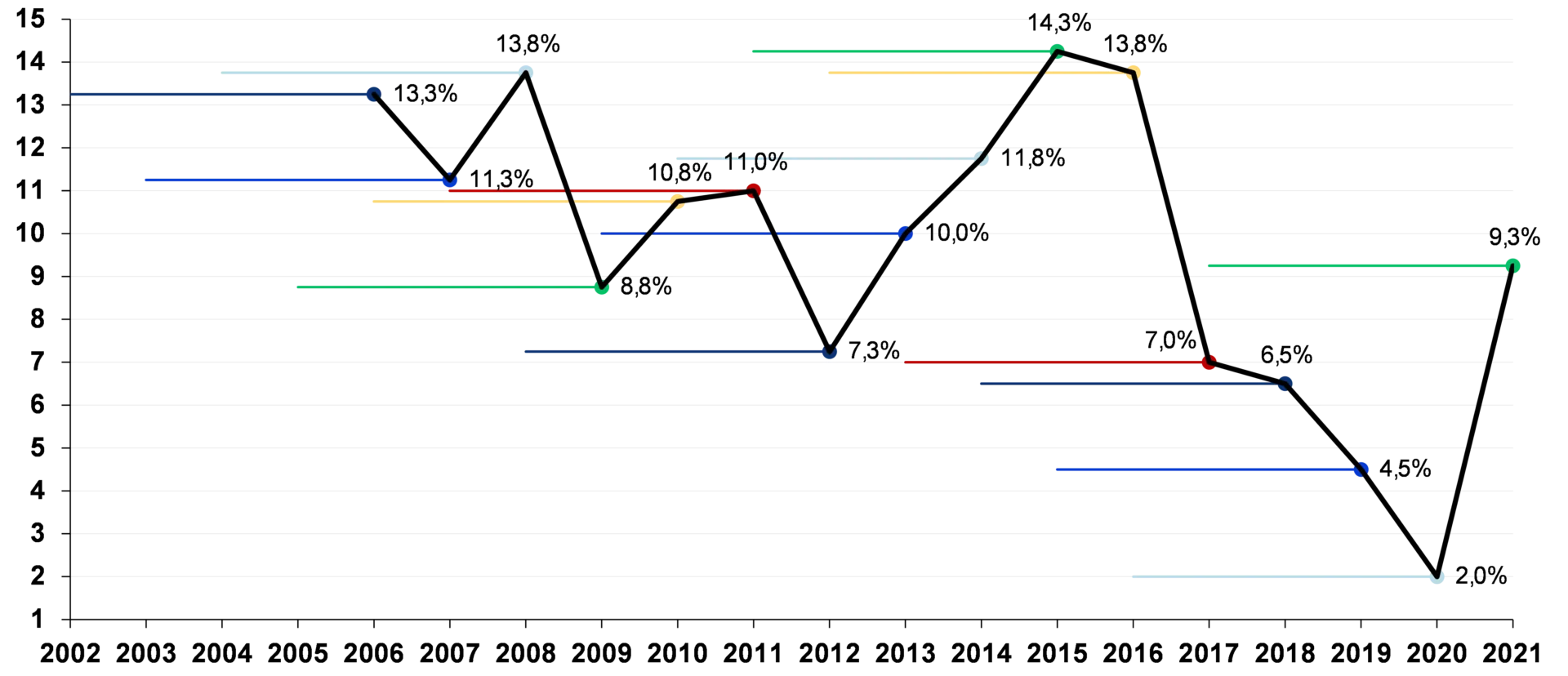

If the market always got its SELIC rate projections right, the long-term chart with projections and forecasts would be as illustrated below:

Chart if SELIC rate projections were always correct

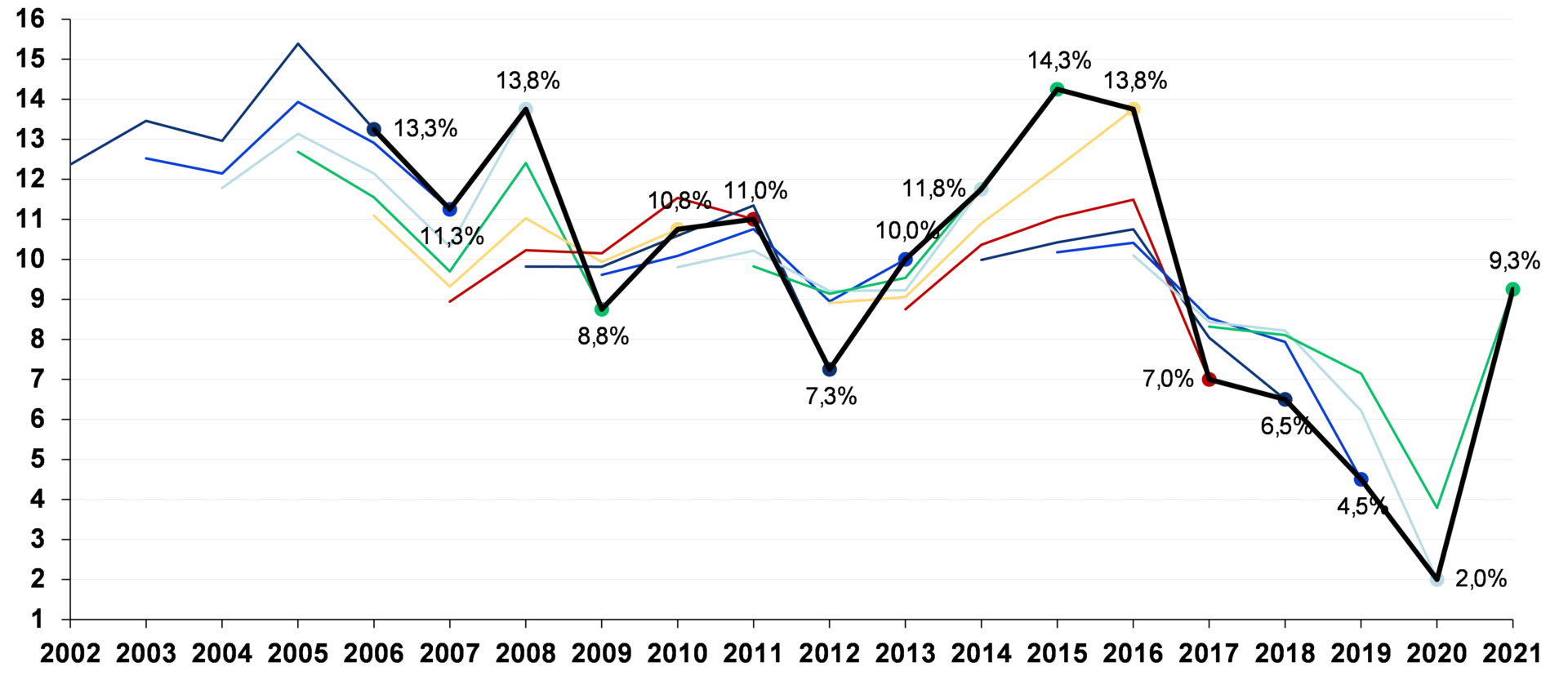

Now let's look at the graphs comparing the actual projections for the SELIC rate, GDP, the dollar (USD/BRL), and the IPCA with the actual values over the last 20 years. They're a bit complex, but the way to interpret them is: the more curved the colored lines, the greater the errors in the market projections. The black line represents the actual values.

Projections vs. Actual Values – SELIC Rate

Note how the projections are heavily anchored to the current interest rate. Projections for the 2021 SELIC rate tracked the rate's evolution between 2017 and 2020, making the projection made in 2020 for the following year more erroneous than the projection made in 2017 for 2021.

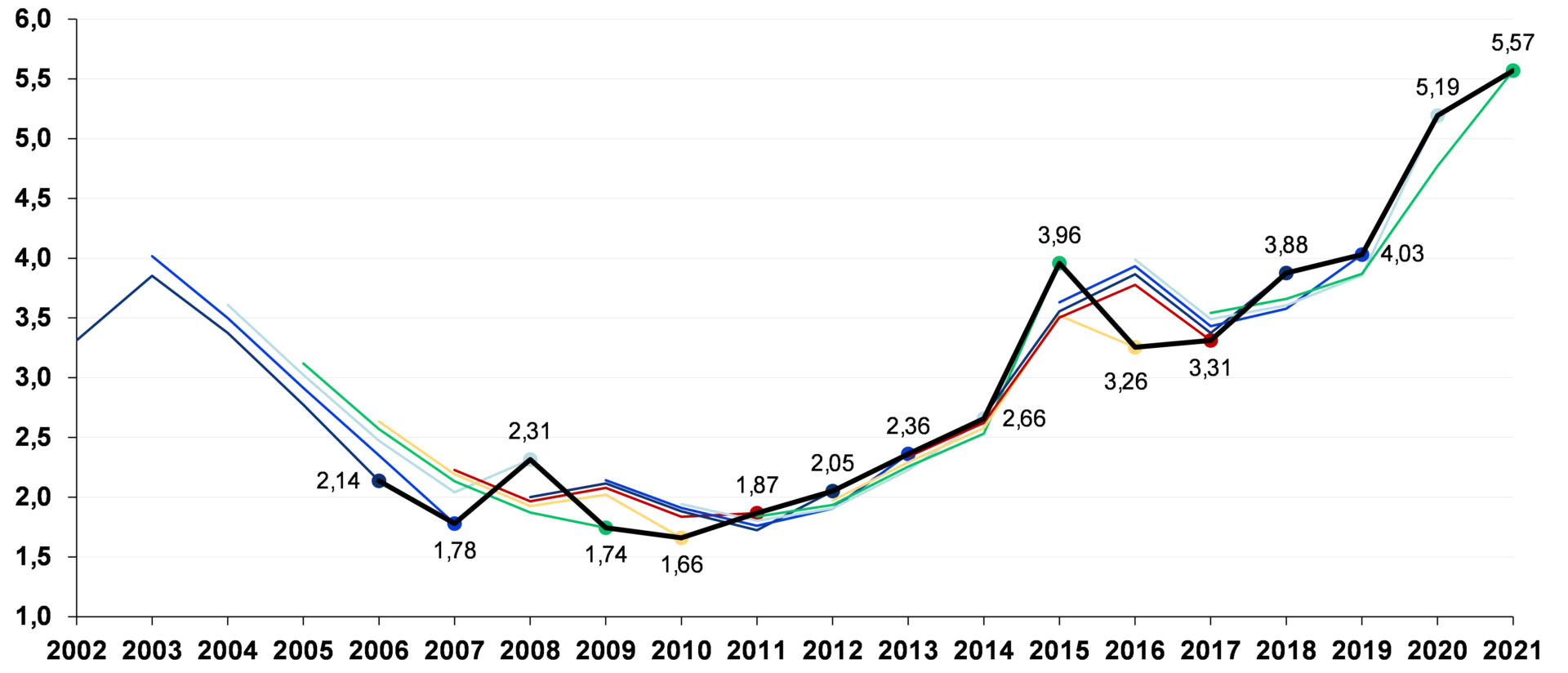

Projections vs. Actual Values – Dollar (USD/BRL)

For the dollar, the anchoring effect of the exchange rate at each moment is once again evident. Projections vary little from the exchange rate at the time they were made, and their predictive power is quite low.

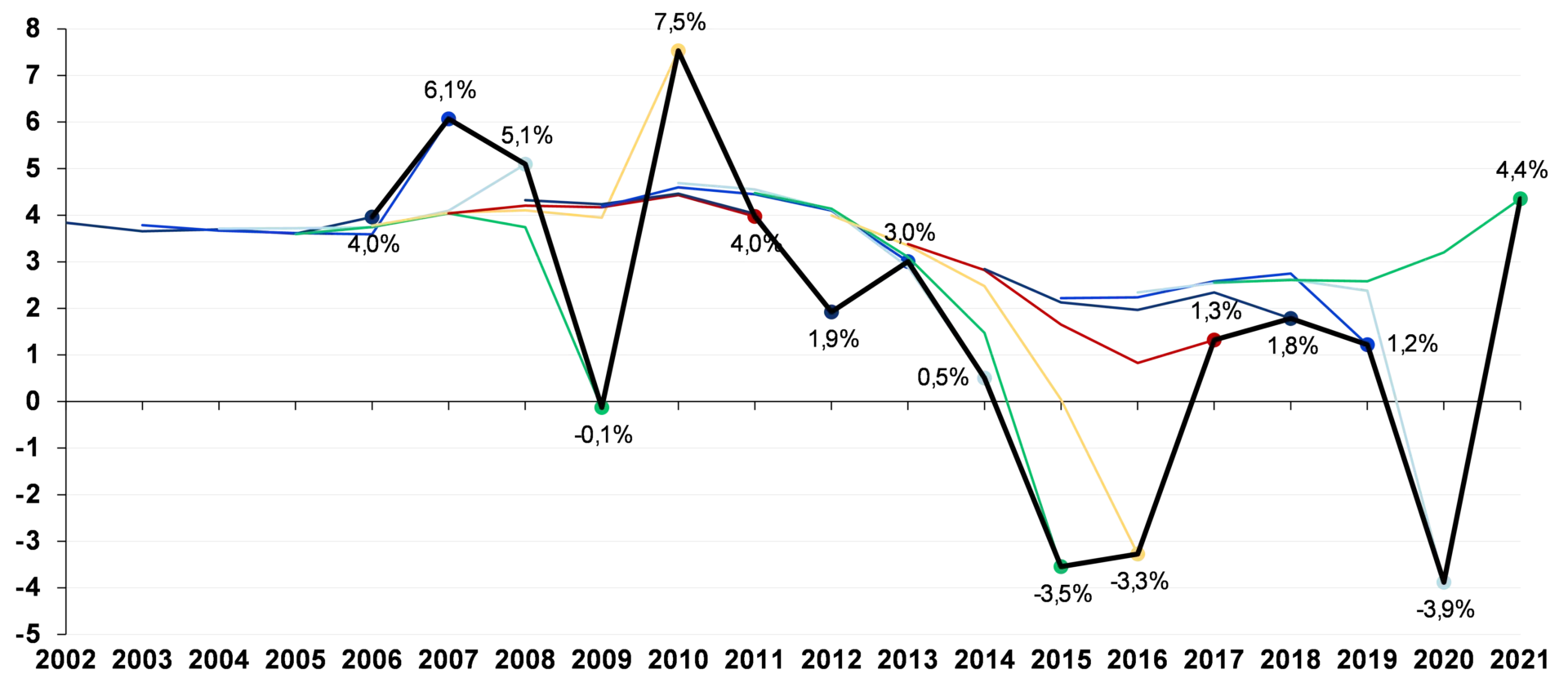

Projections vs. Actual Values – Brazilian GDP Growth

In GDP projections, the market seems to always assume an average growth rate between 2-4%. All years of growth outside this range were not anticipated by the market.

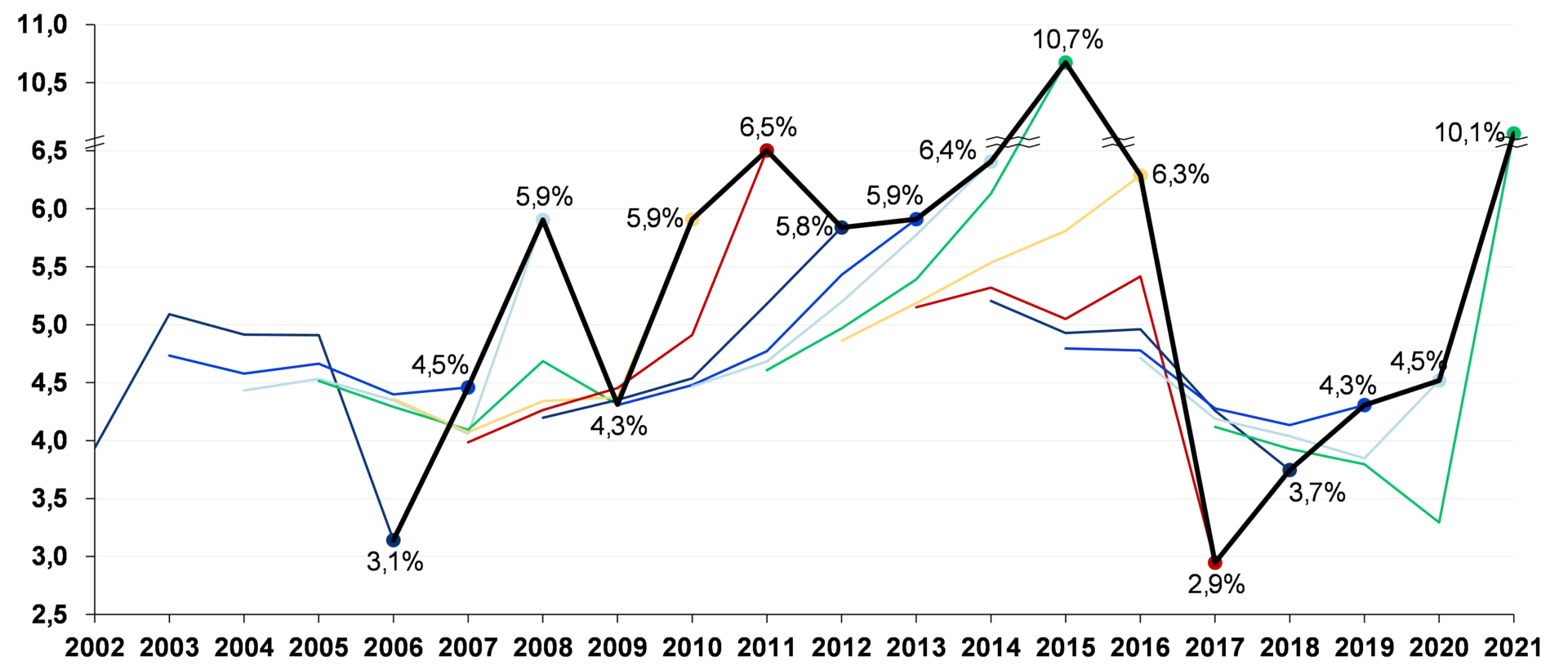

Projections vs. realized values – IPCA

For inflation, the same effect is present: the market typically expects something between 4.0 and 5.5%, and is wrong whenever actual inflation falls outside this range.

In short, market projections for key macroeconomic variables are far from accurate... Remembering that these projections are made by teams of experts from Brazil's largest financial institutions, it seems unreasonable to expect anyone to be able to get much more accurate than this consistently over time.

Our approach

We approach this problem in a simple way, but one that has worked for us for almost 9 years, and has worked for other investors with similar investment philosophies for decades: we don't try to project macroeconomic scenarios. This approach stems from the reflection that, as uncomfortable as living with this uncertainty may be, there is no benefit to our investments in replacing the discomfort of uncertainty with the comfort of an illusion of knowledge about the future.

Assuming that it is not possible to predict the macro future, the strategy of buying stocks when the macro outlook is good and selling when it is bad would lead to the undesirable result of buying high and selling low.

Another important consideration is that, in long-term theses like ours, we're likely to experience both good and bad years, from a macroeconomic perspective. Therefore, our strategy is to identify good companies with resilient business models that are capable of weathering the crises that will certainly occur in the future, and to buy shares in these companies when their prices are quite attractive, regardless of the current macro scenario.

What are we doing now?

Finally, to practice. We are now alongside foreign investors, buying the shares of our fellow countrymen who have decided to migrate to fixed income, as the Brazilian stock market seems cheap to us, and we are finding interesting investment opportunities in a quantity we haven't seen in years.

After the recent stock market crash, we were able to deploy a significant portion of the capital we'd been holding in cash for months. In parallel, this year, Ártica's partners and management team made new contributions to our fund, as did several longtime investors who also decided to allocate more capital to Ártica Long Term FIA.

We appreciate the trust of our investors, for sticking with us even when we decided to go against the current, and we remind you that we should still hope for the stock market to fall, as we want to buy new shares as cheaply as possible!