Is it possible to overcome the CDI?

Dear investors,

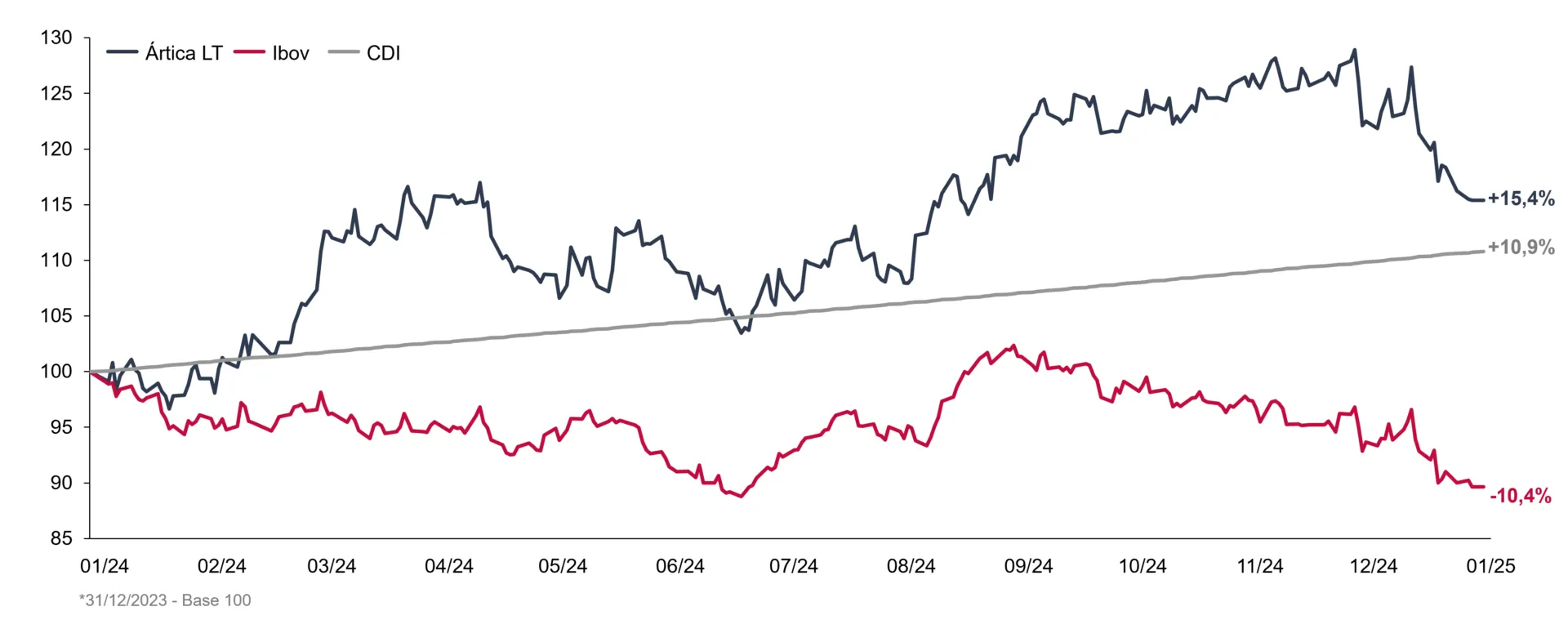

The IBOV ended 2024 with a return of -10.36%, reflecting the market's negative sentiment regarding equities that has persisted for several months. Most investors have been shifting their capital from equities to fixed income, attracted by the SELIC rate already at 12.25% and forecast to reach 14.25% in the coming months. This move has been interpreted as an obvious strategy in the current context.

In parallel, Ártica Long Term ended 2024 with a return of +15.40%, above both the IBOV and the CDI.

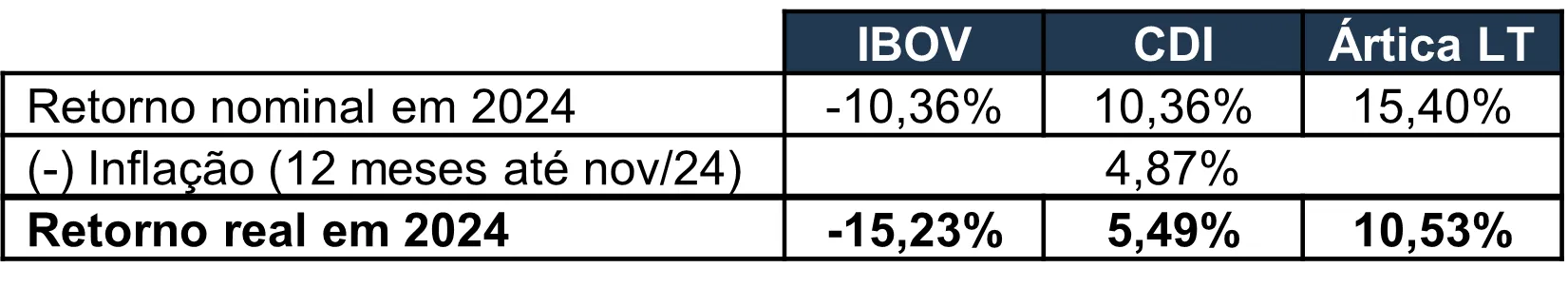

Comparing the real rate of return of Ártica Long Term and the indexes, the difference in additional purchasing power generated for our investors becomes clearer:

Return comparison in 2024

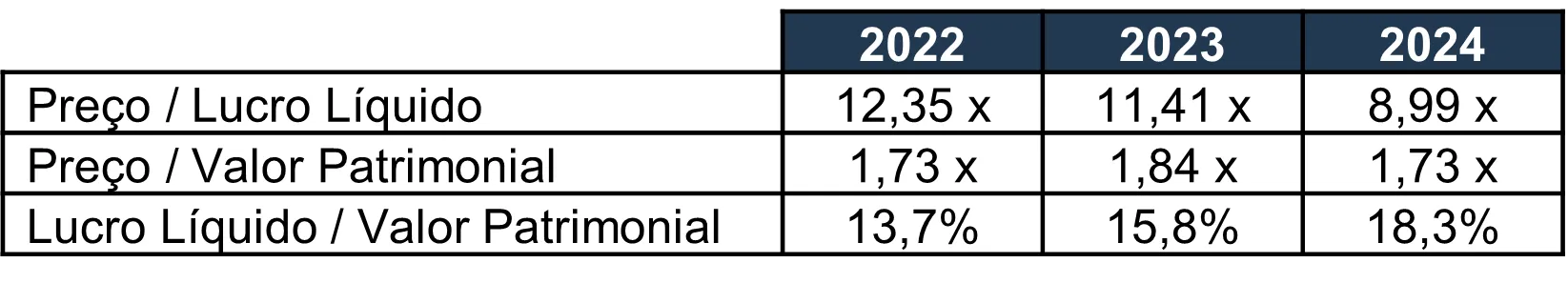

The result raises concerns that the prices of the stocks we have in our portfolio have risen more than they should have and may now be expensive, but this impression is dispelled by a quick analysis of how the weighted averages of the multiples and profitability of the stocks in our portfolio have evolved in recent years:

Average multiples of the Ártica Long Term FIA portfolio

Note: Weighting by portfolio share at the end of 2024. To calculate 2024, the results for the 12 months up to 3Q24 (latest available to date) were considered. MLAS3 was excluded from the P/E analysis due to losses in the period.

The price increase was purely due to an increase in our companies' profitability. Relatively speaking, prices fell. The 2024 P/E multiple was 27.2% lower than that of 2022. So, we pose the following question: investing in companies that have been improving their results but still have their stock prices falling, in relative terms, seems like a good or bad idea? Better or worse than the CDI?

Let's take a step back to look at the situation more conceptually.

Fixed income and variable income prices move in the same direction

There's a strong bias toward focusing on the most readily available data. Thus, we track stock prices and the annual rate of return on fixed-income securities. This creates confusion because every asset has both a price and an expected return, and these indicators are inversely proportional. If a security yields R$ 100 per year, this return is equivalent to 10% of the invested amount if the security's price is R$ 1,000 and 20% if the price is R$ 500. In other words, the lower the price of the same asset, the higher its expected rate of return should be, and vice versa.

In fixed-income securities, the rate of return is determined, and the price of the security fluctuates freely. When market rates of return are rising, it means that security prices are falling. In stocks, the same logic applies: when prices are falling, it means that expected rates of return are rising. Therefore, there is an incongruity in being excited about fixed income when rates of return rise (and prices fall), but discouraged about stocks when their prices fall (and expected rates of return rise).

Floating-rate securities, although also classified as fixed income, have a fixed price and a variable rate of return. This is analogous to a stock with a fixed price. In this case, it makes sense to be excited when interest rates rise, but this type of security carries a reinvestment risk, as high interest rates now don't guarantee a good return over the maturity period. If interest rates fall, the option would be to sell floating-rate securities to buy something else, but the price of stocks and fixed-rate securities is expected to have already risen during the interest rate decline.

Having clarified the confusion created by the convention of tracking inversely proportional indicators, let's get to the point of why interest rates are rising in Brazil.

Interest, inflation and the impact on the real economy

Throughout 2024, we followed the clash between the government, which is suffering from high interest rates on public debt, and the Central Bank, which claims that high interest rates are necessary to combat inflation. We wrote about the dynamics between government spending, inflation, and interest rates in our September 2024 letter. For our current purposes, it suffices to recall that the interest rate hike projected today is justified by the diagnosis that the Brazilian government is overspending, as this contributes to rising inflation and requires the central bank to raise interest rates as a counterbalance.

Added to the problem of rising public spending while fighting inflation, the Brazilian government is running a deficit. Excessive spending causes public debt to grow even further and also increases the risk of government bonds. Governments with debts in their own currency do not default on them, but they can force the Central Bank to arbitrarily issue more currency (print money) to pay off the debts, generating inflation.

The practical effect of this process is that the government appropriates a portion of the capital of those with assets backed by the national currency (fixed-income securities in reais) and distributes this capital to the beneficiaries of public spending. This last point has received less discussion. Government spending always ends up in the pockets of public employees and companies that provide services to the government, which, in turn, have their own expenses with individuals and companies not directly related to the government. In other words, the primary impact of financing public spending through inflation is negative for those with fixed incomes and positive for the real economy.

The side effect that harms the private economy is rising interest rates, which increase the cost of corporate debt and reduce the availability of credit for consumption, dampening demand. However, these effects are not distributed equally among companies. Indebted companies that have no connection to consumer chains fueled by government spending are harmed, while debt-free companies operating in sectors with demand fueled by public spending may benefit.

Two conclusions can be drawn immediately. The first is that variable income encompasses companies from such diverse sectors that any generalization about the category is often quite flawed. The second is that it's not obvious to consider fixed income a safer investment than stocks when the problem is a government deficit and accelerating public spending.

Another advantage of stocks is that real assets don't have their value eroded by inflation. Fixed-rate securities will certainly lose value in an inflationary environment, but companies won't, as their value is constituted by operations, various assets, intellectual property, etc., which have intrinsic economic value. If the currency loses value, the price of these assets rises to preserve their real economic value.

This doesn't mean that a scenario of excessive government spending is desirable for stock investors, because the long-term impact of deficits and inflation is to reduce trust in the government, drive away foreign capital, and reduce the country's productivity, since government capital allocation isn't primarily aimed at economic efficiency. However, it's better to hold stocks than fixed-income securities in this scenario. The recent stories of Türkiye and Argentina are practical examples of this.

In Turkey, inflation due to excessive government spending had long been high (15-20% per year), but it spiraled out of control in 2022 (peaking at 85% per year) and remains high to this day (~50% per year). However, the Turkish stock market rose 29% per year in US dollars from the end of 2021 to the end of 2024. In Argentina, in the 5 years prior to the entry of the MILEI (2019-2023), average inflation was 79% per year. During this period, the Argentine stock market rose 19% per year in US dollars.

What is the chance that the macroeconomic scenario projected today will materialize?

Keynes argued that economic projections were always made by extrapolating the current scenario into the future, except for specific effects that could be predicted with reasonable confidence, even though he knew that the assumption of the continuity of unpredictable factors was highly unlikely to materialize. Lacking an alternative, this practice became conventional, and the asset valuation process was considered correct if done this way. This observation is made in the book *The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money*, published in 1936, and the same practice remains unchanged to this day.

The convention is old, but it hasn't become more effective over time. Macroeconomic projections are notoriously unpredictable precisely because of the number of random factors implicitly assumed to be constant within them. Just remember how much the narrative of what the near future would hold has changed over the past year. Looking at the longer term, it's clear that this was no exception. Forecasts change constantly as new facts materialize, and the accuracy rate of any given macroeconomic theses is quite low.

Consensus on macroeconomics often ends up becoming collective errors. Even so, a large number of investors consider the prevailing theories at the moment as key factors in making capital allocation decisions, which seems to us to be a poorly recommended approach because, beyond the history of errors, nothing widely publicized could offer an informational advantage that would lead to better-than-market decisions. If it's in the newspaper, it's already in the price.

We prefer to maintain the intellectual honesty of admitting that we don't know what will happen with interest rates, inflation, the Lula administration's fiscal policy, or any other traditional macroeconomic variables. But this isn't a new situation. We've never had good predictions about things like this, and we've still achieved good returns. The key point was made long ago by Warren Buffett: there are important, predictable factors, and also important, but impossible, factors. The best allocation of time is to worry about what is predictable, rather than wasting effort on what is unpredictable.

The good old investment strategy

When the environment is turbulent and confusing, it is a good practice to go back to basics.

Companies have value because they offer a product or service that society desires. This value could be lost if demand declines or is captured by competitors. Therefore, a defensive portfolio should focus on sectors where demand is stable and companies whose competitive position is sustainable.

If interest rates are unstable, high debt can cause negative surprises in financial expenses and may affect the company's ability to continue investing and operating at a competitive pace. Therefore, it is prudent to avoid highly leveraged businesses in unstable scenarios.

The final principle is to buy cheap, to offset any negative surprises that turbulent economies can bring. This step should be the most difficult to execute for companies that meet the previous criteria, but it is quite common for stock prices to fall in tandem when market sentiment deteriorates in Brazil. Part of the explanation likely stems from the volume of investments linked to foreign investors, multimarket funds, index funds, and quantitative funds, which typically do not perform in-depth fundamental analysis on each company and, in aggregate, likely represent more than 70% of B3's trading flow (there is no detailed data to confirm the exact percentage).

We are among a minority of investors who still follow the old strategy of evaluating each opportunity based on its long-term fundamentals. Even fewer are those who truly acknowledge ignorance about the macroeconomic future and focus solely on the microeconomic factors of each business.

Our current portfolio was built according to these few basic principles. We invest in companies with sustainable competitive advantages, in sectors with stable demand, and that are currently trading cheaply on the stock market. Market volatility throughout the year simply forced us to rebalance some positions at certain times, and the rather abrupt stock market drop in December allowed us to invest in shares of companies we've been coveting for some time (we'll discuss these new positions with Ártica Long Term investors at the next quarterly earnings call).

We share the general concern about the situation in our country, but we remain optimistic about the return potential of our portfolio of companies, handpicked to face Brazil's uncertain future, and we believe we have a good chance of continuing to outperform the CDI in the long term.